Deconstructing the 20-20-20 Rule for digital eye strain

Many ODs recommend the 20-20-20 Rule to patients to help alleviate eye strain from digital device usage. But few know its origins. Brian Chou, OD, FAAO, FSLS, digs deep to discover who coined the tagline and why.

Figure 1.

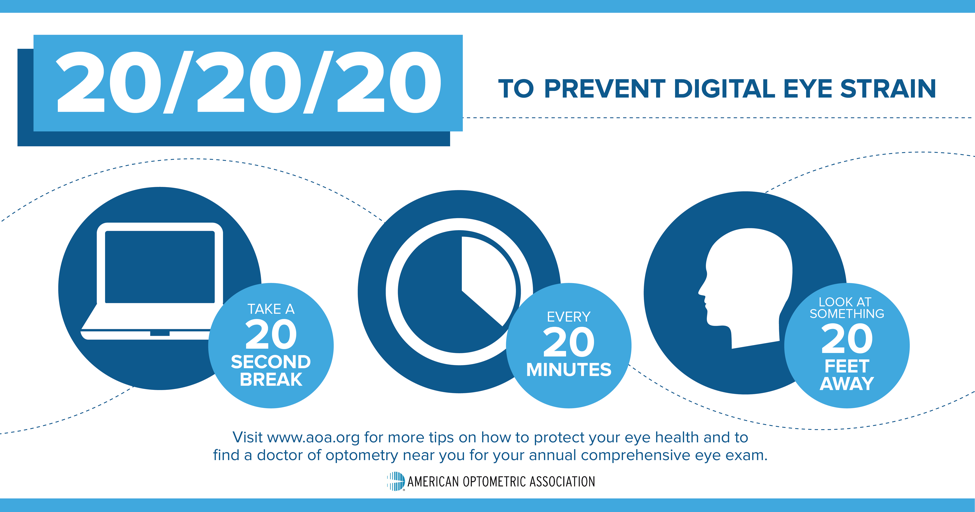

Most optometrists have heard of the 20-20-20 Rule for preventing and relieving digital eye strain. The catchphrase suggests taking a 20 second break every 20 minutes by looking 20 feet away.

Numerous sources now refer to it, including the American Optometric Association (Figure 1) and the American Academy of Ophthalmology.1,2 Maybe you, like many other eyecare professionals, offer this guidance to your patients. But have you ever wondered where this came from?

In the past year, I’ve observed The Rule mentioned enough times in consumer and trade media that I began questioning where it came from. Was this guidance based on evidence, or did its popularity snowball from nebulous origins?

I suspected the latter, believing that The Rule became famous for being famous. This article tells how I tracked down its origin.

Previously from Dr. Chou: 7 strategies for fitting keratoconus patients

Started by an engineer?

With some sleuthing on the Internet, I came across a 2014 blog by an engineer in India which mentioned that he learned of the 20-20-20 Rule from his eye doctor.3 I e-mailed him several times but got no response. I started wondering, was this engineer-without any background in eye care-the person that started The Rule?

I remembered how Airborne, the dietary supplement marketed to prevent the common cold, was created by a school teacher. Could the 20-20-20 Rule be another example in which a layperson started something that became popular and resonated with the public without supportive evidence for efficacy? I had to dig deeper.

Google trends

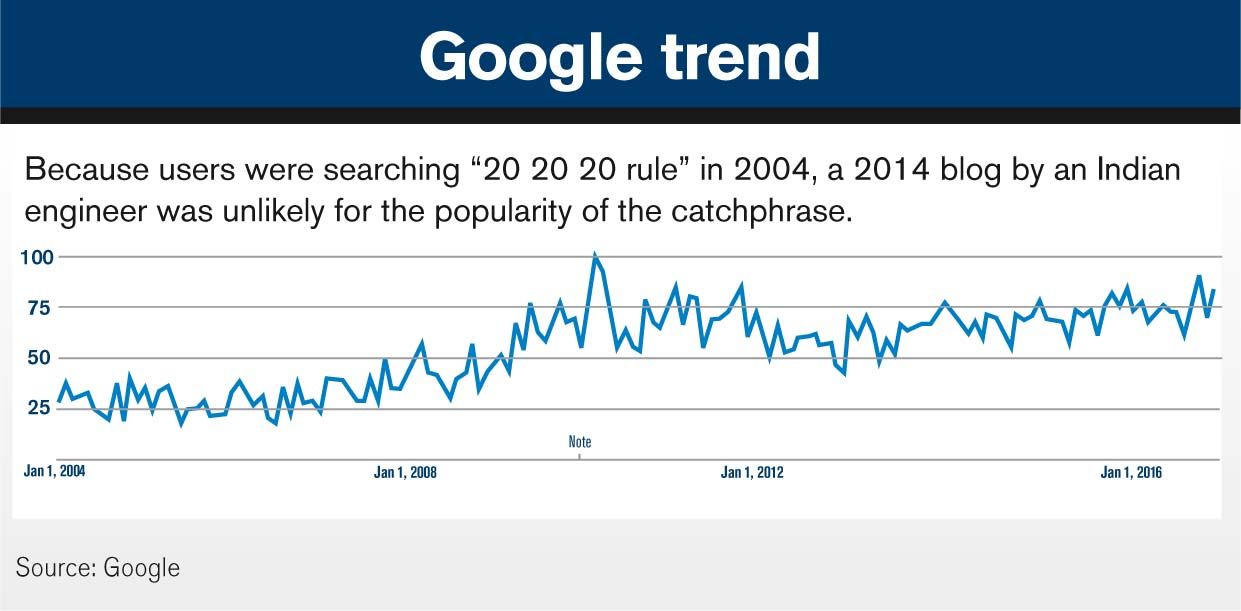

From January 2004, up to today, the number online searches for “20 20 20 rule” on Google approximately doubled (Figure 2). The existence of users searching for this term in 2004 told me that it was unlikely that the 2014 blog article by the Indian engineer was responsible for popularizing the catchphrase.

Yet the confounding factor is that there are also 20-20-20 rules pertaining outside of eye care.

Figure 2.

Other uses

My research showed me that the 20-20-20 Rule is found in other disciplines, such as the military, bariatric surgery, and drug addiction.

The 20-20-20 Rule for military divorce was enacted in 1982 under the provisions of the Uniformed Service Former Spouses’ Protection Act.5

A military spouse qualifies for medical benefits and commissary and exchange privileges for the remainder of life if the spouse was married for at least 20 years, the service member performed at least 20 years of service creditable for retirement pay, and there is at least a 20-year overlap of marriage and military service.4

Deepening the intrigue, a food writer in 2012 coined a 20-20-20 rule for eating after bariatric surgery, suggesting to chew a mouthful of food 20 times before swallowing, putting down utensils for 20 seconds before the next mouthful, and to eat this way for a period of 20 minutes.6

Related: How digital devices are affecting vision

There is also a 20-20-20 rule for a cognitive-behavioral approach to treating drug addiction, describing how the therapist should spend the first, second, and third 20-minute periods during an hour-long session with the patient.7

The upward trend of web searches for “20 20 20 rule” could represent inherent growth of Internet use along with interest in how The Rule pertains not only to the eyes, but for other areas. My next step was to look as far back as Google indexed.

Jackpot!

Under Google web search, the “Tools” dropdown allows users to select a custom date range for the search term. Knowing that Google incorporated on September 4, 1998, one of the earlier indexed pages with search results for “20 20 20 rule” was on the California Optometric Association website8 with a date of February 1, 2001, showing in the search results snippet.

It was an article written by Jeffrey Anshel, OD, FAAO, a colleague who practices in San Diego County like me. He promptly returned my e-mail inquiry about the origination of the catchphrase. He confirmed that he coined the phrase for eye care.

Talking with Dr. Anshel

Dr. Anshel said he came up with the 20-20-20 Rule idea around 1991. At the time, he was lecturing in the corporate world on how to relieve computer vision stress and writing his book, Visual Ergonomics in the Workplace,9 first published in 1998.

In the early 1990s, Dr. Anshel started Corporate Vision Consulting after seeing many patients coming into the office with “strange” vision concerns.

These concerns included late-day headaches and developing myopia in their late 30s, Dr. Anshel says. The only common thread he found was patients using computers for extended hours. He realized he needed to educate the public on how to use computers in a manner that would reduce eye strain by promoting good “visual hygiene’ addressing traditional near-point problems.

“In speaking to corporate workers, I needed a way to get them to take breaks while at the same time allowing them to accomplish their work,” Dr. Anshel says. “The general ‘rule’ at the time was to take a 15-minute break every two hours. Yet most people with visual stress noticed problems earlier than two hours into their workdays.”

Related: How digital device usage is affecting youth

Thus, the 20-20-20 Rule was born.

Dr. Anshel says The Rule gives computer users a quick and easy “tag” to remember when using their computers.

“The tag came from TV and radio interviews that time,” he says. “The interviewers asked what people can do about computer eyestrain, so I honed this into something easy to remember. I started with the ‘3B’ approach: blink, breathe, and break. Then the 20-20-20 Rule came out of the ‘break’ recommendation.”

The basis behind the 20-20-20 Rule, according to Dr. Anshel, comes from studies that found benefits of shorter, more frequent breaks for musculoskeletal disorders.10-13 He adapted the information to the visual system.

Despite the popularity of The Rule, no peer-reviewed studies to date have validated, let alone evaluated this technique. While evidence-based support for The Rule is welcome, Dr. Anshel asserts that the Rule does not stop or reverse myopia development or progression.

More than ocular effects

Our society’s general malaise may come from more than the ocular effects of digital device use.

Part of the malaise is sequelae from digital device addiction, forged by the variable reward of checking for e-mails, text messages, and social media notifications.14 Similar to playing a slot machine, every so often, you win and your brain gets a dose of “feel-good” dopamine. Take smart phones away, and just like with chemical dependency, the withdrawal symptoms arrive. Namely, we feel anxious from the fear of missing out (FOMO) and may even experience “phantom vibration syndrome” in which we anticipate an incoming message notification when there is none.15

That is why many of us compulsively and mindlessly reach for our phones, with millennials leading the way by checking their phones 157 times a day.16 The result is a distraction sickness in which our time and attention is taken from us.17 For some susceptible individuals, including young digital natives, social media can worsen anxiety, depression, self-identity, and body image.18-20

These complex and nuanced effects on our psychological wellbeing from digital device use may not be easily fixed by wearing blue-light–protecting glasses or practicing the 20-20-20 Rule. A digital detoxification requires preventative advocacy for ethical user interface design. One such effort is led by Tristan Harris, the former Google employee who made bare how the profitability of social media companies is currently aligned with making their content addictive.15 Harris’s Time Well Spent initiative (www.timewellspent.io) is a great start toward understanding how our fascination with digital media strains our minds, possibly even more than our eyes.

Mystery solved

While researchers are working to figure out how screen time impacts our eyes-and perhaps even more importantly, our behavior and psychology-the fact is that we currently have patients complaining about ocular discomfort which they attribute to digital device use.

Related: Hackathon series puts focus on digital eye care

This is where you may recommend the 20-20-20 Rule. Dr. Anshel conceived it in the 1990s with a reasonable basis to believe it can help. Since then it has increased in popularity with the growth of digital device use and concerns over eye-related consequences. Ironically, greater awareness of The Rule has come in part because it is spread through digital media.

While Dr. Anshel regrets not trademarking the concept, he says, “I’ve gone to many ergonomic conferences, and attendees recognize me as ‘The 20-20-20 Guy.’ It is nice to be remembered and acknowledged that way.”

References

1. American Optometric Association. Computer Vision Syndrome. Available at: https://www.aoa.org/patients-and-public/caring-for-your-vision/protecting-your-vision/computer-vision-syndrome?sso=y. Accessed 2/22/18.

2. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Computers, Digital Devices and Eye Strain. Available at: https://www.aao.org/eye-health/tips-prevention/computer-usage. Accessed 2/22/18.

3. Agarwal A. The 20-20-20 Rule for Reducing Computer Eyestrain. Digital Inspiration. Available at: https://www.labnol.org/software/computer-eye-exercise/14069/. Accessed 2/22/18.

4. Ask Ms. Vicki. Explaining the 20/20/20 Rule in Military Divorce. Military.com. Available at: http://www.military.com/spouse/relationships/ms-vicki-explaining-the-20-20-20-rule-in-military-divorce.html. Accessed 2/22/18.

5. Wikipedia. Uniformed Services Former Spouses' Protection Act. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uniformed_Services_Former_Spouses%27_Protection_Act. Accessed 2/22/18.

6. BariatricCookery.com. Do You Know The 20:20:20 Rule? Available at: https://www.bariatriccookery.com/202020-rule. Accessed 2/22/18.

7. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Therapy Manuals for Drug Addition. A Cognitive-Behavioral Approach: Treating Cocaine Addiction. Available at: https://archives.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/cbt.pdf. Accessed 2/23/18.

8. California Optometric Association. Improving Visual Comfort at a Computer Workstation. Available at: https://www.coavision.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageID=3638. Accessed 2/22/18.

9. Anshel JR. Visual ergonomics in the workplace. AAOHN J. 2007 Oct;55(10):414-20; quiz 421-2.

10. Chakrabarty S, Sarkar K, Dev S, Das T, Mitra K, Sahu S, Gangopadhyay S. Impact of rest breaks on musculoskeletal discomfort of Chikan embroiderers of West Bengal, India: a follow up field study. J Occup Health. 2016 Jul 20 58(4):365–372.

11. NIDirect Government Services. Safe computer use. Available at: https://www.nidirect.gov.uk/articles/safe-computer-use. Accessed 2/22/18.

12. Henning RA, Jacques P, Kissel GV, Sullivan AB, Alteras-Webb SM. Frequent short rest breaks from computer work: effects on productivity and well-being at two field sites. Ergonomics. 1997 Jan;40(1):78-91.

13. Victorian Trades Hal Council. Breaks for computer/VDU users? Available at: http://www.ohsrep.org.au/ohs-in-your-industry/labour-hire/breaks-for-computervdu-users. Accessed 2/22/18.

14. Bosker B. The Binge Breaker. Atlantic. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/11/the-binge-breaker/501122/. Accessed 2/22/18.

15. Lin YH, Chang LR, Lee YH, Tseng HW, Kuo TBJ, Chen SH. Development and Validation of the Smartphone Addiction Inventory (SPAI). PLoS One. 2014; 9(6): e98312.

16. SMW Staff. Millennials Check Their Phones More Than 157 Times Per Day. Social Media Week. Available at: https://socialmediaweek.org/newyork/2016/05/31/millennials-check-phones-157-times-per-day/. Accessed 2/22/18.

17. Sullivan A. I Used to Be a Human Being. NY Mag. Available at: http://nymag.com/selectall/2016/09/andrew-sullivan-technology-almost-killed-me.html

18. Royal Society for Public Health. #StatusofMind. Available at: https://www.rsph.org.uk/our-work/policy/social-media-and-young-people-s-mental-health-and-wellbeing.html. Accessed 2/22/18.

19. Steers MLN, Wickham RE, Acitelli LK (2014). Seeing Everyone Else's Highlight Reels: How Facebook Usage is Linked to Depressive Symptoms. J Social Clin Psych. 2014;33(8)701-731.

20. Pantic I. Online Social Networking and Mental Health. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2014 Oct 1;17(10):652–657.

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.