Diagnosis reveals ODs’ key role in diabetes identification

Extensive testing, consultation with primary-care doctor key to proper treatment

A 62-year-old male came to my office recently complaining of blurred vision for the last two weeks.

Earlier that day, he had been diagnosed with atrial fibrillation by his primary-care practitioner (PCP), and was prescribed a systemic beta blocker (carvedilol, Coreg) and was referred to a cardiologist.

His thyroid function studies had also been “slightly abnormal”-a longstanding issue. He complained about the blurry vision to his PCP, who told him it was likely due to hypothyroidism.

The patient’s previous medical history included having been treated for prostate cancer two years ago as well as a recent prostate specific antigen (PSA) value of zero

Upon questioning, he noted that he had been under great stress during the holidays and had been losing weight despite excess consumption of calories.

He also said that he had been drinking more water than usual. I asked him if his blood glucose had been measured earlier that day, and he was not sure.

Related: Role of insulin therapy in diabetes and diabetic retinopathy

With his most recent glasses (updated months earlier), the patient was 20/200 in each eye, which was easily corrected to 20/20 with a 3.00 D increase in myopic correction.

The patient is 73 inches tall and weighs 165 lbs, giving him a body mass index (BMI) of 21.77 kg/m2.

I checked his blood glucose in-office, which measured 515 mg/dl. A point-of-care glycosylated hemoglobin (A1C) was completed (measuring 14 percent, equivalent to an estimated mean glucose of 355 mg/dl over the last eight to 12 weeks). Clearly, this patient has diabetes.

Game over-right? Nothing more to do but refer the patient back to the PCP and get started on treatment, right?

Wrong.

Next steps

I sent the patient to a local pharmacy to buy a home blood glucose meter and to text me a few more of his values that evening.

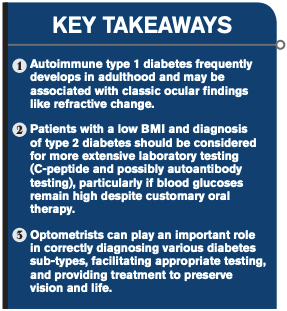

All were above 500 mg/dl. Given the patient’s low BMI, symptoms, and profound hyperglycemia, I was suspicious that he had latent autoimmune diabetes of adulthood (LADA), a type 1 diabetes that develops later in life, or-less likely but far more worrisome-pancreatic cancer given his prior medical history.

Related: How diabetes affects your patients

I phoned the PCP the next morning to advise her that the patient required insulin therapy and that I wanted her to run a C-peptide assay to assess whether or not he was making any of his own insulin.

I also recommended antibody testing if the C-peptide values were low to confirm a diagnosis of autoimmune diabetes.

We discussed the differential diagnosis (LADA versus atypical type 2 diabetes versus pancreatic cancer), and she agreed to see the patient that afternoon.

I received another text from the patient saying he had been started on insulin glargine (Lantus, Sanofi), 15 units before bedtime. I texted him back indicating that long-acting insulin in isolation was a poor choice unless he would no longer be eating food.

The next day, he reported his fasting blood glucose measured 250 mg/dl, but that after lunch, it had jumped back above 500. This was predictable. He forwarded me his C-peptide results the following day, which were 1.0 ng/ml (normal value=0.5 to 2.0 ng/ml).

He was still making some of his own insulin, but not excessive amounts as is typical of type 2 diabetes (C-peptide typically 4). It was now down to LADA versus pancreatic cancer.

Follow-up

Five days’ worth of long-acting insulin monotherapy and chronic hyperglycemia later, I was able to get the patient in with an endocrinologist, who ordered glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD-65) antibody testing along with anti-pancreatic islet cell antibody (ICA) testing.

The latter was negative, but the former came back as 1708.2 U/ml (normal values=0 to 5.0 U/ml). It turned out the patient did have LADA and was placed on basal-bolus insulin therapy.

LADA

It is estimated that around 10 percent of adults diagnosed with type 2 diabetes actually have LADA. The disease is characterized by a relatively slower autoimmune destruction of insulin-producing pancreatic beta cells than in “classic” type 1 diabetes seen in younger patients.1

Related: Nutrition in the future of primary-care optometry

Recent analysis has suggested that half of all type 1 diabetes cases are diagnosed after the age of 30, rendering the moniker “juvenile-onset diabetes” obsolete.2

C-peptide is a by-product of pro-insulin cleavage and, as such, is an inexpensive marker of patients’ ability to produce their own insulin. It also serves as an outstanding discriminator between type 1 and type 2 diabetes when the exact diagnosis is in doubt.3

GAD

GAD is an enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of glutamate to the neurotransmitter, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and carbon dioxide. In mammals, GAD has two isoforms: GAD65 and GAD67.

In both type 1 diabetes and LADA, GAD65 and GAD67 are known to be targeted by autoantibodies-which, when positive in tandem with a lower or non-existent C-peptide, is diagnostic of autoimmune diabetes.

Other autoantibodies may also be found, including those to pancreatic islet-cell antibodies (ICA). Of note, autoimmune thyroid disease is also associated with GAD autoantibodies and might account for hypothyroidism in this particular patient.5

Pancreatic cancer is a known cause of secondary diabetes resulting from localized destruction of beta cells. It may manifest as profound hyperglycemia and weight loss with classic diabetes symptoms (excessive thirst and frequent urination), just as in type 1 diabetes and LADA.6

Had this patient’s GAD65 results been normal, he would have been referred immediately to oncology.

More by Dr. Chous: Research initiatives offer treatment options for diabetes patients

References:

1. Stenström G, Sundkvist G, Gottsäter A, et al. Latent autoimmune diabetes in adults: definition, prevalence, beta-cell function, and treatment. Diabetes. 2005 Dec;54 Suppl 2:S68-72.

2. Thomas NJ, Jones SE, Weedon MN, et al. Frequency and phenotype of type 1 diabetes in the first six decades of life: a cross-sectional, genetically stratified survival analysis from UK Biobank. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6(2):122-129.

3. Leighton E, Sainsbury CA, Jones GC. A Practical Review of C-Peptide Testing in Diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2017 Jun;8(3):475-487.

4. Taplin CE, Barker JM. Autoantibodies in type 1 diabetes. Autoimmunity. 2008 Feb;41(1):11-8.

5. Katahira M, Ogata H, Ito T, et al. Association of Autoimmune Thyroid Disease with Anti-GAD Antibody ELISA Test Positivity and Risk for Insulin Deficiency in Slowly Progressive Type 1 Diabetes. J Diabetes Res. 2018 Jul 11;2018:1847430.

6. Munigala S, Singh A, Gelrud A, Agarwal B. Predictors for Pancreatic Cancer Diagnosis Following New-Onset Diabetes Mellitus. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2015;6(10):e118.

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.