Knowing the OD's role in substance abuse

The significant healthcare dilemmas of substance use pose challenges to our society. Michael W. Ohlson, OD, FAAO, discusses an optometrist's role in substance abuse treatment.

Optometrists may be the first healthcare provider to become aware of a patient’s substance abuse problem. Substance abuse is not uncommon in society, and optometrists provide care in primary-, secondary-, and tertiary-care settings.

A U.S. Surgeon General report highlights the scope of the nation’s substance use problem, advising that addiction is a chronic neurological disorder rather than a “moral failing” or a “character flaw” while imploring for change in both the public perception and the health care system.1

The dilemma of handling patients with substance abuse problems, while seldom discussed in training and practice, is relevant to optometry’s role in society. As optometry strives for improved community recognition and increased scope, the responsibilities associated with primary care provision come along for the ride.

In my experience, it’s virtually impossible to avoid contact with patients recently using drugs or presenting to the office while impaired (I had a private practice in the area of the country described in the book Methland).

Substance use disorders (SUD) are defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition as: “clinically and functionally significant impairments caused by substance use, including health problems, disability, and failure to meet major responsibilities at work, school, or home.”

SUDs affected 20.8 million Americans in 2015; this is about the prevalence of diabetes and more than 1.5 times the annual prevalence of all cancers.1

Substance abuse stats

Drug use and abuse is common, affecting patients of any demographic (age, gender, ethnicity, region, socioeconomic, etc.).

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) affects 15.1 million adults (age 18+) and 623,000 adolescents (ages 12-17). Of people age 18 and older, 26.9 percent reported engaging in binge drinking (five or more alcoholic drinks on the same occasion on at least one day in the past 30 days); AUD is more prevalent in the college student population.2

Marijuana use is also prevalent; the National Survey on Drug Use and Health reported usage of marijuana/hashish in the past year as 12.6 percent in people ages 12-17; 32.2 percent in ages 18-25; and 10.4 percent in ages 26 and older.3

Related: Marijuana’s role in optometry and beyond

While marijuana remains illegal under federal law, 29 states and the District of Columbia allow medical marijuana use. Nine states (Alaska, California, Colorado, Maine, Massachusetts, Nevada, Oregon, Vermont, Washington) and the District of Columbia currently permit recreational use.

Opioid abuse is relevant to primary care as well; the epidemic abuse of prescription opioids is a risk factor for heroin use.4

ODs may encounter multiple other drugs, such as the “club drugs” (GHB, Rohypnol, ketamine, MDHD (Ecstasy), LSD), methamphetamine, cocaine, inhalants, anabolic steroids, synthetic cannabinoids (K2, Spice), synthetic cathinones (bath salts), and more.

Managing substance abuse

Evidence exists of knowledge and performance gaps in diagnosing and managing drug use and addiction.

A survey indicated that less than 20 percent of primary-care physicians felt very prepared to identify alcoholism or illicit drug use, while greater than 50 percent of patients reported that their physician did not address their problem.5

A 2012 report from The Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University stated that physicians and other medical professionals receive little education and training in addiction science, prevention, and treatment. These medical professionals also fail to identify the disorder, and they do not know what to do with patients presenting with identifiable signs and symptoms.6

The report concluded that about only one in 10 patients with addictions to alcohol or drugs receives treatment for the condition-this is a treatment gap of 20.7 million citizens.6

Other obstacles to care include:

• Doctor and patient comfort levels

• Limited time with patients

• Availability of services

• Inadequate or poor insurance coverage

• Physician attitude (blaming, bias, misunderstanding).

To address the serious risks associated with extended release and long-acting opioids, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has required a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS), including a REMS-compliant continuing education (CE) program and other tools for prescribers of schedule II and III controlled substances.7

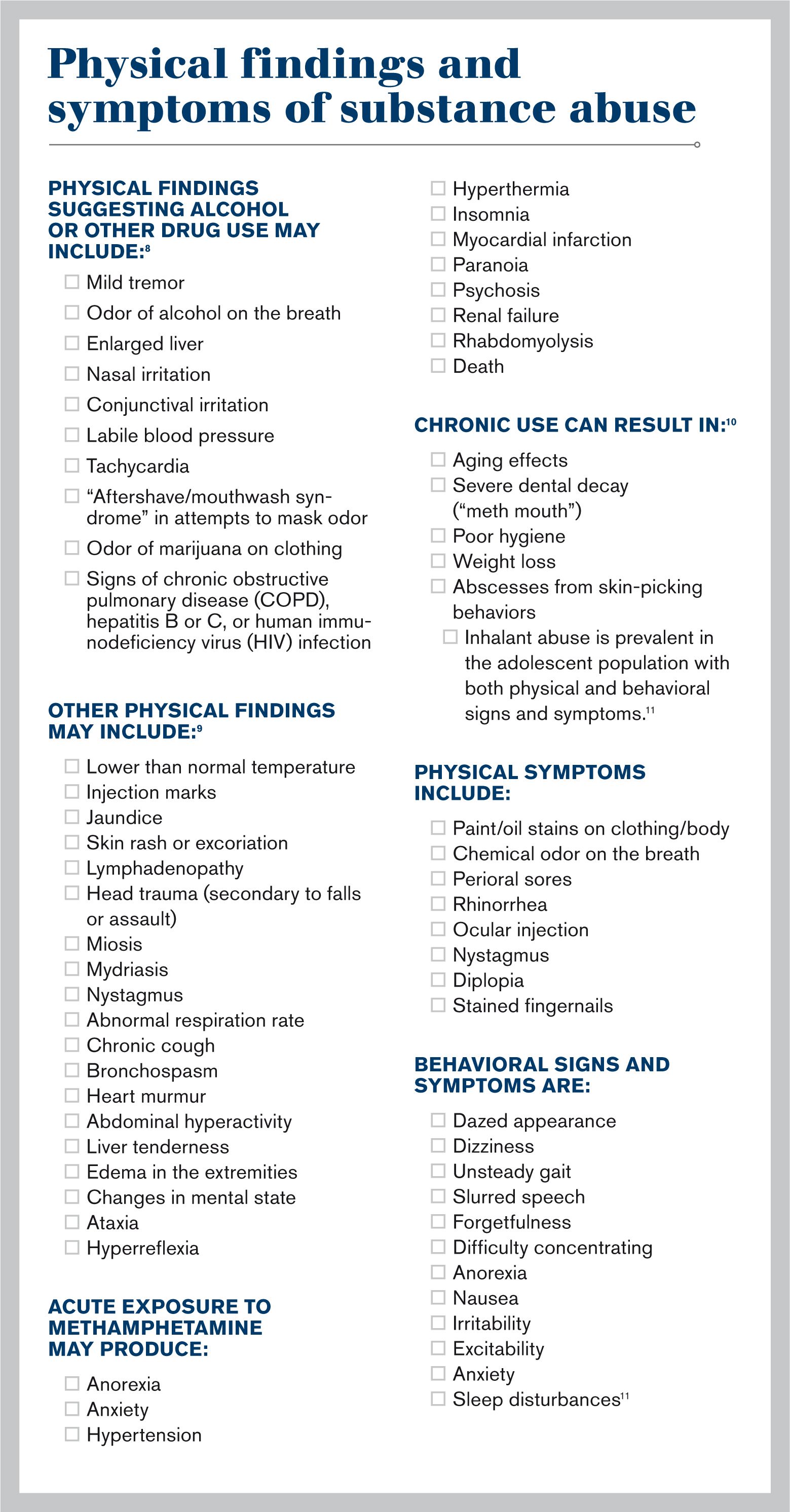

Physical findings suggesting alcohol or other drug use may include:8

• Mild tremor

• Odor of alcohol on the breath

• Enlarged liver

• Nasal irritation

• Conjunctival irritation

• Labile blood pressure

• Tachycardia

• “Aftershave/mouthwash syndrome” in attempts to mask odor

• Odor of marijuana on clothing

• Signs of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), hepatitis B or C, or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection

Other physical findings may include:9

• Lower than normal temperature

• Injection marks

• Jaundice

• Skin rash or excoriation

• Lymphadenopathy

• Head trauma (secondary to falls or assault)

• Miosis

• Mydriasis

• Nystagmus

• Abnormal respiration rate

• Chronic cough

• Bronchospasm

• Heart murmur

• Abdominal hyperactivity

• Liver tenderness

• Edema in the extremities

• Changes in mental state

• Ataxia

• Hyperreflexia

Acute exposure to methamphetamine may produce:

• Anorexia

• Anxiety

• Hypertension

• Hyperthermia

• Insomnia

• Myocardial infarction

• Paranoia

• Psychosis

• Renal failure

• Rhabdomyolysis

• Death

Chronic use can result in:10

• Aging effects

• Severe dental decay (“meth mouth”)

• Poor hygiene

• Weight loss

• Abscesses from skin-picking behaviors

Inhalant abuse is prevalent in the adolescent population with both physical and behavioral signs and symptoms.11

Physical symptoms include:

• Paint/oil stains on clothing/body

• Chemical odor on the breath

• Perioral sores

• Rhinorrhea

• Ocular injection

• Nystagmus

• Diplopia

• Stained fingernails

Behavioral signs and symptoms are:

• Dazed appearance

• Dizziness

• Unsteady gait

• Slurred speech

• Forgetfulness

• Difficulty concentrating

• Anorexia

• Nausea

• Irritability

• Excitability

• Anxiety

• Sleep disturbances11

Related: How vaping affects the ocular surface

Patient screening tools

The U.S. Preventative Services Task Force reported insufficient evidence to recommend screening for substance use disorders other than alcohol, but some have suggested that universal screening may be justified based on the associated prevalence, morbidities, and comorbidities (anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, personality disorders, and intimate partner violence) of substance abuse.5

The National Institute on Drug Abuse recommends screening patients in general medical settings for drug use, including tobacco, alcohol, illicit drugs, and nonmedical use of prescription drugs via the “5 As of Intervention:” Ask (screening), Advise (strong direct personal advice), Assess (determine willingness to change behavior after advice), Assist (help), and Arrange (refer for further assessment, treatment, follow-up).12

Additional quick screening tools include a single-question screen (“How many times in the past year have you used an illegal drug or used a prescription drug for nonmedical reasons?”), the Drug Abuse Screening Test-10, and the AUDIT, AUDIT-C, and CAGE-AID questionnaires.5,13

Direct confrontation is seldom helpful when treating patients with possible substance abuse disorders. Improve outcomes with motivational interviewing techniques such as resisting the “righting reflex,” listening, using a non-confrontational approach so to advise or share information while allowing patients to express feelings about change (“elicit-provide-elicit”), articulating the pros and cons of change (decision analysis), identifying statements patients make in support of change and reflecting such statements back (reflections), and promoting patient self-efficacy to improve confidence in making change (affirmations).5

Once ODs identify substance misuse, refer to primary care physicians with training and experience or to specialty addiction treatment. Additional resources for the patient and the referring doctor may include mutual help meetings (such as Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, Rational Recovery, SMART Recovery), medically supervised withdrawal, and outpatient or residential treatment (such as American Society of Addiction Medicine Physician Finder, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Treatment Locator).

Impaired patients in the office

Acutely impaired patients presenting to the office represent a dilemma for staff and doctors. These patients may intend to drive while impaired by alcohol, illicit drugs, or prescribed medications. This situation represents significant risk of injury and death via motor vehicle accident as well as liability to the practice and doctor.

The ethical dilemma places the duty to prevent harm to the patient and others vs. the need to respect the patient’s rights of autonomy and confidentiality.

Legal problems may develop based upon the varied federal, state, and case law regarding breach of confidentiality, the duty to warn, and the duty to report. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA) permits disclosure of relevant protected health information to family members or law enforcement when the provider believes the patient represents a “serious and imminent threat” to self or others.14

Most state jurisdictions do not specifically address how to handle patients representing danger to others due to current intoxication with regard to confidentiality, but case law indicates that a healthcare provider should minimally inform the impaired patient not to drive.15 Suitable alternatives might include having the patient arrange for a sober friend or relative to drive or calling a taxi or ride-sharing service such as Uber or Lyft.

Decrease your liability risk by documenting the warning to not drive and making reasonable efforts to arrange transportation. In the event of the patient becoming abusive, threatening, or driving while a risk to self and others, it’s reasonable to notify the police.

Because these situations can be expected to occur over the course of a career, consider implementing a written office policy for staff regarding how to manage impaired patients. Suggestions for office policies include: detailed and complete documentation of the incident (this may be kept separate from the patient chart), approaching the patient in a non-confrontational manner, expressing concern regarding driving, offering to find alternative transportation, calling the police if necessary, and confirming coverage with the practice general liability insurer for any potential related problems.16

Optometry’s larger role in health care

Optometry has integrated and embraced many of the 10 Cs of primary care17 as important aspects of our profession. Our Optometric Code of Ethics charges us to keep the patients’ general health paramount, to advise patients whenever consultation with or referral to another healthcare professional is appropriate, to recognize our obligation to protect the health and welfare of society, and to conduct ourselves with compassion.18

The significant healthcare dilemmas of substance use and SUDs pose challenges to our society. As doctors seeing these patients in multiple settings and interacting with other professionals and within interprofessional teams, optometrists have an opportunity to demonstrate an 11th C: compassion.

References

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of the Surgeon General, Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Available at: https://addiction.surgeongeneral.gov/executive-summary.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2017.

2. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol facts and statistics. Available at: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/alcohol-facts-and-statistics. Accessed 1/29/18.

3. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Available at:

https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FFR1-2015/NSDUH-FFR1-2015/NSDUH-FFR1-2015.pdf. Accessed 11/17/17.

4. Prescription Opioids and Heroin. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Available at:

https://d14rmgtrwzf5a.cloudfront.net/sites/default/files/rx_and_heroin_rrs_layout_final.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2017.

5. Shapiro B, Coffa D, McCance-Katz EF. A primary care approach to substance misuse. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88(2):113-121.

6. The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University. Missed opportunity: national survey of primary care physicians and patients on substance abuse. Available at: http://www.centeronaddiction.org/addiction-research/reports/national-survey-primary-care-physicians-patients-substance-abuse. Accessed January 24, 2017.

7. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) for Extended Release and Long-Acting Opioid Analgesics. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/ucm163647.htm. Accessed January 24, 2017.

8. Mercy DJ. Recognition of alcohol and substance abuse. Am Fam Physician. 2003 Apr 1;67(7):1529-1532.

9. Johnson MD, Heriza TJ, St. Dennis, C. How to spot illicit drug abuse in your patients. Postgrad Med. 1999;106:199-218.

10. Winslow BT, Voorhees KI, Pehl KA. Methamphetamine abuse. Am Fam Physician. 2007 Oct 15;76(8):1169-1174.

11. Anderson CE, Loomis GA. Recognition and prevention of inhalant abuse. Am Fam Physicians. 2003 Sep 1;68(5):869-874.

12. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Screening for Drug Use in General Medical Settings Resource Guide. Available at:

https://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/resource_guide.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2017.

13. Weaver MF, Jarvis MA, Schnoll SH. Role of the primary care physician of substance abuse. Arch Intern Med. 1999 may 10;159(9):913-924.

14. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). HIPAA Privacy Rule and Sharing Information Related to Mental Health. Available at:

https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ocr/privacy/hipaa/understanding/special/mhguidancepdf.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2017.

15. Buppert C. Legal obligations to the dangerous patient. Topics in Advanced Practical Nursing eJournal. 2009;9(3). Available at: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/707580. Accessed January 24, 2017.

16. Schoppmann MJ. Intoxicated patients. Fam Pract Manag. 1999 Jul-Aug;6(7):50.

17. Kroenke K. The many C’s of primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2004 Jun;19(6):708-709.

18. Code of Ethics. American Optometric Association. Available at: http://www.aoa.org/about-the-aoa/ethics-and-values/code-of-ethics?sso=y. Accessed January 24, 2017.

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.