3 steps to help you examine patients with ASD

The prevalence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) means that most optometrists can expect to provide care to these patients-yet many ODs feel unprepared to do so.

Approximately 1 out of every 50 children has autism spectrum disorder (ASD), a developmental disability characterized by deficits in social communication and interaction, and restricted and repetitive behaviors.1,2 Though these patients clearly need quality health care, studies show that patients with ASD are less likely to receive the same level of medical care as typical peers.3 Parents of patients with ASD are not as confident in the level of care that their child receives.4 Pediatricians and other primary-care providers acknowledge that they feel less confident in their skills to provide care to these patients.5

Dr. CoulterThe prevalence of ASD means that most optometrists can expect to provide eye examinations to these patients, yet many feel unprepared to do so.

How can optometrists provide eye examinations to patients with ASD? You can prepare by taking three steps.

1. Learn about the core deficits in ASD and their link to behaviors

All patients with ASD have core deficits in social interaction and communication. Some patients may be nonverbal or have minimal speech. These patients may communicate by using an augmentative communication device, computer, or gesturing. Other patients may be very verbal, but their speech may not be appropriate to the context, situation, or task at hand.

In addition to problems in expressive language, patients with ASD have trouble understanding what they hear. For optometrists giving instructions for eye tests, this means that long, wordy directions will not be effective. Keep instructions short and to the point. Include visual supports, such as gestures and pictures, to help your patient understand what to do. Make sure that the pace of your words, gestures, and motor movements is at a rate that your patient can process. Allow your patient time to respond before assuming he or she can’t or won’t participate.

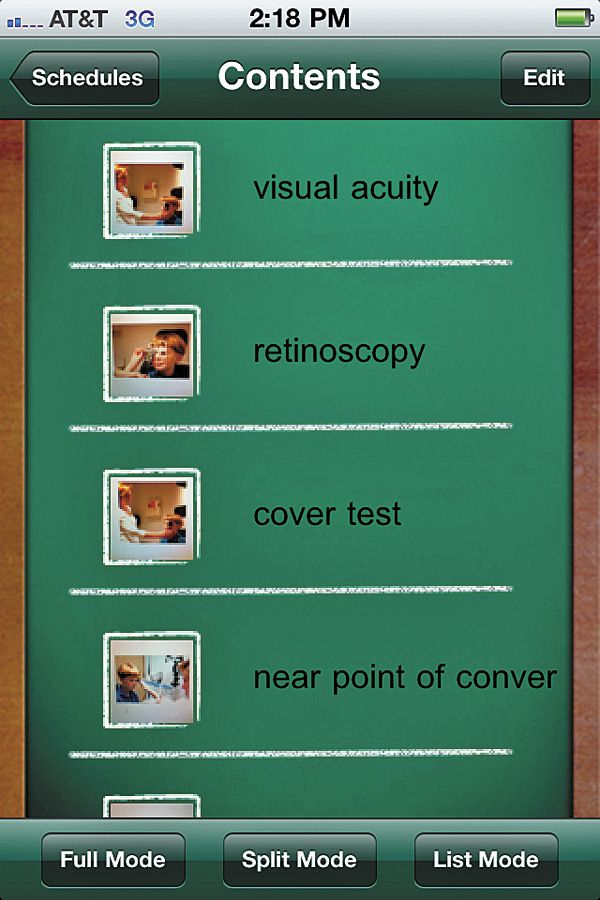

Patients with ASD often have difficulty making transitions, such as switching to a new task or location. The use of a visual schedule, a series of pictures, to represent a sequence of events can be helpful for patients to navigate this process (see Figure 1). Many patients with ASD have fragmented attention, and therefore have difficulty staying on task. The use of affect, or the display of emotion through your voice, face, and gestures, can help the patient with autism to organize his or her thoughts and maintain interaction. Many patients are hypersensitive to touch and may resist wearing glasses or goggles, having their lids touched, or placing their chin or head against equipment. When possible, selecting tests with minimal tactile demands will support success.

Figure 1. A visual schedule.2. Prepare your staff and practice in advance

Discuss the needs of these patients as well as some of their unique challenges. Think about the best time to schedule a patient in your practice who may be particularly sensitive to sound, smells, or being around a lot of people. If possible, obtain prior medical records and provide forms to be completed in advance so that waiting times are reduced.

3. Incorporate modifications and strategies into your eye-testing protocol

For the eye examination, incorporate specific strategies to testing to increase the likelihood of success. In testing visual acuity, most patients with ASD will tolerate an occluder to measure monocular visual acuity. When this does not work, try having the parent or caregiver cover each eye with the palm of his or her hand. Many patients will be able to respond to a Snellen chart. Some nonverbal patients can respond by typing the letters on a communication device, tablet computer, or smartphone. For patients who do not respond to the Snellen chart, use a recognition visual acuity test, such as the Lea Symbol or H-O-T-V test that comes with a response plate of choices. By providing a visual support, acuity becomes a matching task that patients are more likely to understand and participate. Some patients with ASD have poor fine motor skills and so may not be able to point. Allow them to touch the picture or letter with their whole hand.

For color vision testing, use a copy machine to make black and white versions of the correct answers. Allow patients who have trouble responding to match the answer or place the correct number or picture on top of the plate.

To test stereoacuity, consider holding the polarized lenses in a frame with no temples. This eliminates the tactile sensation of having to wear glasses or goggles. Observe whether or not the patient responds to the 3-D wings of the fly or butterfly. Patients who are particularly tactile sensitive may respond to a stereotest, such as the Lang Stereotest, that does not require glasses. Again, consider using copies of the images and having patients match their answer (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. The Lang Stereotest is used to screen young patients for signs of problems with stereoscopic vision.Out-of-phoropter testing may be useful to gauge the patient’s fixation and maintain their attention. To obtain good fixation during retinoscopy, it may be helpful to show a video using a portable computer or iPad. Make this the last test because some patients will fixate on an electronic screen and have a hard time discontinuing to complete other tests. Use objective testing for alignment, vergences, and near point on convergence, such as cover test and prism bar vergences.

Ocular health assessment presents some of the toughest challenges in examining patients with ASD. These patients are hypersensitive to bright lights and touch. Instillation of drops, tonometry, and binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy are particularly difficult. Research suggests that for these patients, anxiety decreases when they feel that they have some control over an unpleasant stimulus.

Optometrists can offer the patient some control, yet not waste time and protect the integrity of the exam. Using portable handheld equipment that does not require a patient to be positioned in a chinrest and headrest may be helpful for anterior segment evaluation. Consider using a transilluminator and clear 20 D lens or an Eidolon Bluminator. A rebound tonometer, such as the ICare, offers a way to take IOPs that requires no anesthetic, has minimal touch, and is quick.

A step-by-step approach may be helpful for drop instillation. :

- Inform the patient. Demonstrate what you are going to do.

- Give the patient a task to do while the sensation of drops wears off.

- Ask the patient to count forward or backward, or sing familiar song. Practice with him one time so he understands what to do.

- Instill the drops or spray as quickly as possible, with eyes open or at the margin of loosely closed eyelids.

- Ask the patient to look at his caregiver or another person. (This encourages the patient to open his eyes and to blink to help distribute the drops.)

Figure 3. For binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy, present the beam incrementally.For binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy, present the beam in an incremental manner (see Figure 3). Tell the patient you will be shining a flashlight. First, shine the light beam on your hand and count from 1 to 5 slowly. Then, shine the beam on the patient’s leg, count from 1 to 5, and then back away. Shine the beam on the patient’s arm and repeat the process. Then, put the BIO on your head and shine the beam into the patient’s eye. To encourage the patient to look in the desired direction, a lighted toy may be held as a fixation target.

Optometrists have an important role in providing comprehensive, high-quality care to patients with ASD. Many patients with ASD may not be receiving basic vision care, including correction for refractive error and ocular health assessment, because their family or caregivers cannot find a provider. By providing eye examinations and vision care, educating families and caregivers, and serving as a community resource, optometrists meet a critical need and fulfill their role as primary eye-care providers.ODT

References

Hyman SL. New DSM-5 includes changes to autism criteria. American Academy of Pediatrics News http://aapnews.aappublications.org/content/early/2013/06/04/aapnews.20130604-1.full.pdf+html. Accessed 6-24-2013.

What is Autism? Autism Speaks. http://www.autismspeaks.org/what-autism.. Accessed 6-24-2013.

Maccabee-Ryaboy N, Golnik A. Autism. Clinical pearls for primary care. Contemp Pediatr 2010. http://digital.healthcaregroup.advanstar.com/nxtbooks/advanstar/cntped_201011/index.php?startid=42. Accessed 6-24-2013.

Liptak GS, Orlando M, Yingling JT, et al. Satisfaction with primary health care received by families of children with developmental disabilities. J Pediatr Health Care. 2006 Jul-Aug;20(4):245-252.

Golnik A, Ireland M, Borowksy IW. Medical homes for children with autism: A physician survey. Pediatrics. 2009 Mar;123(3):966-71.

Three measures for examining patients with ASD

- Learn about core deficits in ASD and their link to behaviors.

- Prepare your staff and practice.

- Incorporate modifications and strategies into your eye-testing protocol.

Eyedrop instillation step-by-step

- Inform the patient. Demonstrate what you will do.

- Give the patient a task to do while the sensation of drops wears off.

- Ask the patient to count forward or backward or sing familiar song.

- Instill the drops or spray as quickly as possible, with eyes open or at the margin of loosely closed eyelids.

- Ask the patient to look at his caregiver or another person, which helps distribute the drops.

AUTHOR INFO

Rachel A. Coulter, OD, MS, is an associate professor Nova Southeastern University.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a developmental disability that affects 1 out of every 50 children. Patients with ASD are hypersensitive to bright lights and touch. Instillation of drops, tonometry, and binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy are particularly difficult. But you can successfully examine these patients by learning about the core deficits, preparing your staff and practice, and modifying your eye testing protocol.

Research suggests that for these patients, anxiety decreases when they feel that they have some control over an unpleasant stimulus.

When possible, select tests with minimal tactile demands to support success.