The dangers of starting and stopping glaucoma treatment

The notion of patients not coming in as advised for eye examinations can be troubling. For example, when a patient has an eye disease as potentially significant as glaucoma and chooses to ignore its presence, there is cause for concern on the part of the doctor.

The notion of patients not coming in as advised for eye examinations can be troubling. For example, when a patient has an eye disease as potentially significant as glaucoma and chooses to ignore its presence, there is cause for concern on the part of the doctor.

A chain of events is set into motion when a patient does not show up to our clinic for follow-up care. Several attempts (typically over several days to a couple of weeks) to reach the patient by phone are undertaken and documented in the patient’s record. If that mode of communication fails, we send a letter by certified mail to the patient imploring him to follow up with us or someone else.

We also offer a referral in instances such as changes to the patient’s insurance coverage. Beyond that, there is not much we can tangibly do to convince that particular patient to continue care.

Previously from Dr. Casella:

Not long ago, a patient returned for a continuation of glaucoma care after more than two years of no-shows for appointments.

Initial diagnosis and treatment

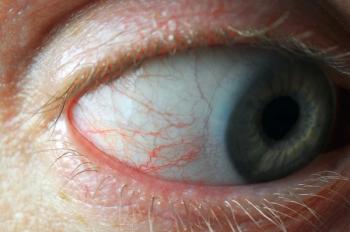

The patient is a 52-year-old African-American male who has a previous history of mild bilateral primary open-angle glaucoma. His medical history is significant for arterial hypertension and a familial history of cataracts and glaucoma. He is otherwise healthy and takes a diuretic medication for his blood pressure. He is a mild myope in each eye and is not a smoker.

When I first saw him years ago and performed glaucoma testing, his average intraocular pressures (IOP) were in the high 20s in each eye. His vertical cup-to-disc ratios were suspicious and were determined to be 0.65 in each eye. His optic discs were of average size and shape.

Central corneal thicknesses were 535 µm for the right eye and 526 µm for the left (thin to average). Angles were open to the ciliary body in each quadrant by gonioscopy with flat iris approaches and mild pigment in each trabecular meshwork. Visual field studies were unremarkable for each eye, and spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) studies showed thinning of each eye’s temporal retinal nerve fiber layer.

Related:

At the time of diagnosis, I did not have access to ganglion cell complex analysis on my SD-OCT device. I was performing macular scans on all of my glaucoma patients and glaucoma suspects in anticipation of such software becoming available and being retroactive. Running the patient’s macular scans through the ganglion cell complex algorithm when it became available did show thinning in each eye.

After compiling and analyzing the patient’s diagnostic data and having a brief conversation with him regarding the evidence, I initiated therapy with a prostaglandin analog and set a target pressure of 15 to 18 mm Hg for each eye. He left with a sample of medication and returned as directed one month later.

Restarting treatment

At the follow-up visit and the next several visits over the course of several years, his IOPs remained well controlled in the mid-teens in each eye. He did not return for over two years. He explained to me that he had lost his job and his insurance at the time. He found another job shortly thereafter with insurance benefits but explained to me that he had been busy and had put off coming back.

I welcomed him back and documented my advice to him that glaucoma can lead to blindness if left untreated. I also documented that he expressed understanding of that possibility and agreed to resume treatment. His IOPs were high that day, and I performed a comprehensive eye exam and took photographs of his optic nerve heads. Upon review and comparison to previous photos, his optic nerve heads were unchanged.

Related:

Six weeks later, his IOPs were back down in the mid-teens. I performed subsequent visual field and SD-OCT studies and found no progression. He was concerned that he had damaged his eyes by ignoring the apparent need for therapy for several years, and he was relieved that I could find no additional glaucomatous damage to his eyes.

At that point, he said, “Do you think I need to keep taking this stuff?”

Success with continuation

By asking that question, he gave me a great opportunity to discuss the nature of glaucoma progression to the best of our current knowledge. I explained to him that glaucoma is a progressive disease, but it can take years to determine the mere presence of progression-not to mention the progression rate. I also explained that glaucoma is a slow disease and that time is typically on one’s side with comparison to many other diseases.

I explained that, with him at age 52 and in relative good health, I was not concerned about him having visual problems from glaucoma in the next month or even the next year, but his high IOPs were putting many of those potential years of good vision in jeopardy.

My usual speech is, “If you were 105 years old, I would turn you loose and tell you to have a nice life, but you are not. It is my job to ensure that those years are filled with healthy eyes and good vision, and that’s the only reason I am here.”

He saw my point, smiled, and agreed to continue treatment. He has a follow-up visit scheduled for this fall. I hope he shows up.

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.