From craniotomy to Charles Bonnet syndrome

Case complexity underscores the importance of interdisciplinary communication.

This case highlights the downstream visual effects of multiple neurological procedures following a meningioma diagnosis. The complexity of this case magnifies the importance of interdisciplinary communication in optimizing patient care along with the lack of predictability in visual outcomes following neurological procedures. This patient underwent multiple bouts of MRI imaging and 3 craniotomies to manage her meningiomatosis over the course of 7 years. Her gradual decline in acuity and increasing visual hallucinations during this period pointed to a diagnosis of Charles Bonnet syndrome (CBS) shortly after her third brain surgery. In this report, the patient’s extensive ocular history will be reviewed along with her clinical presentations and management plan. Her prognosis ultimately lies in her ability to cope with her vision loss and adapt to this degree of visual impairment.

Case presentation

A 75-year-old Caucasian woman presented to the Storm Eye Institute at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) in Charleston on January 8, 2024, in obvious emotional distress for gradually decreasing vision in both eyes, more recently her left eye. This gradual decline in vision had been ongoing since 2013 when she noted no improvement in visual acuity after cataract surgery that year. Her report of a blind spot in the superior temporal quadrant of her left eye shortly after that cataract surgery revealed a bitemporal hemianopsia on visual field testing, leading to a prompt MRI that was positive for a benign meningioma involving the suprasellar region and sphenoid wing. This finding was the catalyst for what would become long-term management of meningiomatosis, including regular MRI scans to watch for growth, craniotomies for optic nerve involvement in 2016 and 2023, and subsequent episodes of vision loss, visual disturbances, and transient visual spells.

This patient’s neurological needs were primarily being managed by the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida, where she had her previous craniotomy procedures done. She had a house in Charleston and expressed interest in having her records sent to a local neurologist/neuro-ophthalmologist there to establish care for when she wasn’t in Florida. Over the course of 7 years, this patient had notably decreasing vision in her right eye that started with reduced peripheral vision and evolved into loss of central vision until she was counting fingers. She presented to the MUSC clinic in January 2024 complaining of decreased vision in her left eye following her most recent meningioma removal in April 2023. In addition to the decreased vision OS, she reported visual hallucinations that were increasing in frequency and duration, occurring upward of 20 hours per day. She described these hallucinations as “scenes” that typically involved people she did not know dressed in costumes. Sometimes the scenes were disturbing, and she reported seeing people at all times of the day despite knowing they were not truly there. These episodes were also beginning to interrupt her sleep patterns and hinder her quality of life.

Her medical history included migraine headaches, osteoporosis, hyperthyroidism, meningioma removals (in 1987, 2016, and 2023), and mild mitral regurgitation. Current medications included levothyroxine sodium (Synthroid), vitamin B12, vitamin D3, and sertraline (Zoloft). She reported no known drug allergies.

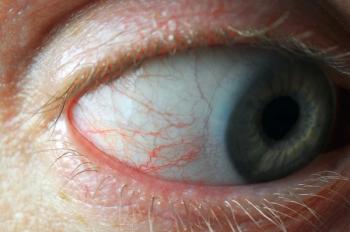

Entering acuities at this exam were no light perception (NLP) in both eyes with no improvement with pinhole. She was not wearing any glasses at the time and manifest refraction was not performed. There was minimal light reaction in both pupils. She was unable to follow a moving target to assess her extraocular muscles and demonstrated completely restricted fields with confrontation visual field (CVF) in both eyes. Tonometry was performed and yielded pressures of 16 and 15 mm Hg in the right and left eyes, respectively.

All adnexal and slit lamp findings were normal except for mild dermatochalasis in both eyes. Her posterior chamber intraocular lens implants in both eyes were clear and centered. A posterior fundus exam revealed peripapillary atrophy and a tilted disc with a c/d ratio of 0.5 in both eyes. There was diffuse optic nerve pallor of both nerves. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) imaging was performed and showed progressive thinning of the RNFL, particularly in the right eye, compared with previous OCT data from records in 2019 and 2021.

Epidemiology of Charles Bonnet syndrome

CBS is experienced exclusively by patients characterized as having low vision. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Subhi et al revealed the prevalence of CBS as being 1 in 5 low-vision patients, a staggeringly high statistic.1 Other studies note prevalence in low-vision patients at anywhere from 1% to 10%. CBS is independent of any mental or behavioral disorders, yet many patients experiencing these hallucinations are overlooked or mismanaged because they struggle to speak up about their experiences for fear of being labeled as mentally unstable. Almost 1 in 3 CBS patients reports feeling anxious or stressed about their quality of life.2

Common etiologies for CBS include age-related macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, cerebral infarctions, high myopia, retinitis pigmentosa, optic neuritis, and others. Most of these conditions are found in older people with the mean age of those with CBS being 70 to 85 years old. The frequency and intensity of visual hallucinations have been shown to correlate with the degree of vision loss rather than linked to specific ocular or neurologic conditions.3

Patients with CBS present with complex visual hallucinations that most often accompany concurrent visual changes, specifically in central acuity and visual field loss. The decrease in acuity or visual field loss can stem from a variety of disorders/diseases and can arise from any malfunction along the visual pathway, from the eyes themselves to the optic nerve to the brain.2 Many cases often go undiagnosed or are misdiagnosed as a psychiatric disorder due to the nature of the hallucinations and correlation to demographics of older adults.

As in the case of our patient, the decline in central and peripheral vision can accompany an increase in seemingly random eye movements as patients attempt to compensate for the lack of visual stimulation. As visual stimulation declines, it has been noted that the frequency, duration, and intensity of hallucinogenic episodes tend to increase.4 What people see can vary, but the most-reported hallucinations include landscapes, people, animals, geometric shapes, people dressed in costumes, and imaginary creatures. Episodes have been reported to last anywhere from a few minutes to hours and include images that can move or remain stationary.

The most widely accepted theory for why these visual hallucinations occur is due to visual sensory disruption of afferent connections to the visual cortex, leading to disinhibition of cortical connections that stimulate vision. This disinhibition leads to the spontaneous firing of regions in the visual cortex, resulting in formed images and hallucinations despite lack of physical visual stimulation.2 Some compare this phenomenon to the phantom limb theory where subjects who have recently lost a limb can still feel sensations of pain despite the limb having been removed. Similarly, these patients still experience visual sensations despite being unable to physically see them.

Diagnosis and treatment

This patient’s CBS was diagnosed by a neurologist in Charleston with the aid of our medical records. She presented to our clinic following this diagnosis to evaluate her status of vision and visual prognosis, and to lead her to the best resources for this lifestyle change.

Careful posterior segment evaluation and fundus photos revealed advanced optic nerve pallor in both eyes. OCT was unable to be performed as the patient could not fixate. The patient was educated about her most recent procedure at the Mayo Clinic and the importance of follow-up with her neurology team. We discussed the extent of pallor noted in both optic nerves and the fact that her vision likely would not return given her NLP status in both eyes for the past 9 months.

A referral to neuro-ophthalmology and low-vision services was made in hopes of exploring other treatment/management options. Mild cases of CBS often necessitate reassurance and minor coping habits during episodes. In severe cases of CBS, such as with our patient, behavioral techniques and medications can be used to help suppress hallucinations. Excessive and intentional blinking during hallucinations has been found to be helpful to dampening their intensity in addition to rapid eye movements away from the formed images. Pharmacotherapies, such as antipsychotics and anticholinesterase inhibitors, have proven to have mixed efficacies in decreasing hallucinogenic effects.

The mainstay of treatment and management of CBS is reassurance, counseling, and optimizing visual function for these patients. Psychological therapies, like meditation, relaxation training, hypnosis, and cognitive remodeling aid in diminishing anxiety surrounding hallucinations. Referrals to low-vision services have proven beneficial for patients maintaining some remaining vision or visual field.3

Discussion

This case revealed the importance of interdisciplinary communication in managing complex visual and neurological disorders. It also highlighted the lack of predictability in visual prognosis following seemingly benign surgical procedures. Uncovering this patient’s chronic struggle with meningiomatosis at an eye exam was paramount to preventing vision loss earlier in life, yet this case goes to show that even when standard protocol is followed, there is no guarantee that vision will be saved. Patient education is key when dealing with sight-threatening conditions so their expectations can be managed should something go awry during care.

This case also goes to show that there can be long-term effects of extensive vision loss. While many patients who fall into this category are typically referred to low-vision services and left to their care, this situation unveiled the more complex and abstract implications of losing sight that a white cane and magnifiers will not fix. The added layers of mental counseling, compassion, reassurance, and behavioral modifications are components of a low-vision referral that I had never experienced before, yet are necessary to maintaining and elevating the remaining quality of life for this patient.

References:

Subhi Y, Schmidt DC, Bach-Holm D, Kolko M, Singh A. Prevalence of Charles Bonnet syndrome in patients with glaucoma: a systematic review with meta-analyses. Acta Ophthalmol. 2021;99(2):128-133. doi:10.1111/aos.14567

Rojas L C, Gurnani B. Charles Bonnet Syndrome. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; StatPearls [Internet]. July 25, 2023. Accessed

July 8, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK585133/Charles Bonnet syndrome (CBS). Macular Society. Reviewed

May 2021. Accessed July 8, 2024. https://www.macularsociety.org/macular-disease/macular-conditions/charles-bonnet-syndrome/Dhooge PPA, Klevering BJ. Charles Bonnet syndrome: a condition

of the visually impaired. Ann Eye Sci. 2022;7:22. doi:10.21037/aes-22-11

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.