How to combat vernal keratoconjunctivitis

It is a precarious position considering the desire to find the perfect remedy- yet with vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC), there is no magic bullet.

How do you tell a parent her child will have to “power” through the next decade of life with a condition that will cause blepharospasm, discomfort, and mucous discharge upon awakening?1

It is a precarious position considering the desire to find the perfect remedy- yet with vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC), there is no magic bullet.

I was taught in my early years of training to research an enigmatic disease state and to pivot to where you can to succeed in treating the condition. I have learned that VKC can be treated effectively with a stepladder strategy by understanding the historical background and pathophysiology.

Previously from Dr. Cooper:

What history tells us

The first known description in the literature of VKC came from Arlt in 1846 where he reported three cases of perilimbal swelling in children.2 Almost a decade later, Desmarres depicted the limbal findings representative of VKC in slightly “lymphatic” children who were experiencing photophobia.2

After his death in 1870, von Graefe had his work published the following year delineating the “pavement-like granulations” of the conjunctiva which has become one of the hallmark signs of this inflammatory/immunological disease state.2

These doyens of ophthalmology, along with many others, classified at different times the condition as spring catarrh, phlyctenula pallida, circumcorneal hypertrophy, recurrent vegetative conjunctiva, verrucosa conjunctiva, and aestivale conjunctiva, calling attention to the various aspects of this disease.3 Even though these authors accepted VKC as an allergic entity, there were and still are many gaps in the knowledge of the etiology and pathophysiology.

The groundwork was laid to pursue more ambitious research in the immunological realm. This was done to discern whether this disease state had deeper implications than a mere Type 1 hypersensitivity reaction.

Pathophysiology living of daylights

With a breadth of cytological, immunohistological, and molecular biological studies peering at the multifaceted nature of VKC, this persistent and severe form of ocular allergy is now classified as both IgE and non-IgE mediated hypersensitivity.2,4

Supporting the IgE front are the abundance of CD4+T helper cell type 2 (Th2) lymphocytes and expression of costimulatory molecules in the conjunctiva. Subsequently, this facilitates the release of multiple cytokines and chemokines on to the ocular surface, inducing local production of IgE along with subsequent mast cell degranulation.5

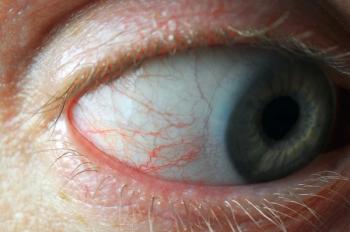

These overexpressed cell types lead to a paucity of Th1 cytokines in the tears and serum, causing perpetual eosinophilic late phase action (Type IV hypersensitivity) to interfere with normal tissue. Remodeling is evident in the presence of Horner-Trantas dots at the limbus, punctate keratitis, shield corneal ulcers from epithelial macroerosions, and giant papillary cobblestone-like formations scaffolding the tarsal plate due to overgrowth of conjunctival connective tissue.6,7

Specific IgE are identified in only 50 percent of patients, corroborating the concept that non-IgE-mediated activation pathways are present. Not all cases illustrate a positive response to skin tests for common allergens or flare-ups consistent with an environmental burden.2,5

The presence of a veritable smorgasbord of pro-inflammatory cell types and mediators in the conjunctiva, tears, and serum of VKC patients lends credence to the potential complex interaction of the immune, endocrine, and nervous systems.8-10

Related:

Epidemiology and early intervention treatment strategy

As with many conditions, there are subtypes that can make some treatment decisions easier to discern based on severity. VKC can be broken down into conjunctival, limbal, and a mixed reaction with a male gender preference along with an age range of 1 to 22 years (mean 6 ±3.7 years).11,12

The most common and most severe cases present from hot, arid environments such as the Mediterranean basin, West Africa, and the Indian subcontinent. Patients found in my clinic and many others ranging from European, Hispanic, South American, and Asian descent also show signs of VKC.1,12,13

With regard to treatment, conjunctival signs of micropapillae without corneal involvement are easily managed with chronic daily antihistamines exhibiting mast-cell stabilizing properties. These are commercially available as generic olopatadine 0.1%, Pazeo (olopatadine 0.7%, Alcon), Bepreve (bepotastine, Bausch + Lomb), and Lastacaft (alcaftadine, Allergan).

All of these agents in varying degrees competitively and reversibly block histamine receptors in the conjunctiva and eyelids. This inhibits the actions of the primary mast-cell–derived mediator, helping to reduce the late phase of the allergic response. In combination with mast-cell stabilizers, these agents inhibit mast-cell degranulation by limiting the release of histamine, tryptase, and prostaglandin D2 (PGD2).14,15

A word of advice: To avoid a headache, do not use either an antihistamine or a mast-cell stabilizer as isolated units. They may be unsuccessful-leading to a delay in appropriate treatment.

Related:

Signs and therapy

When there are giant papillary signs coupled with stringy mucous and corneal neovascularization, it would be prudent to initiate steroid pulse therapy for between two and four weeks. Accompany this with a taper, depending on the product. These signs illustrate the tenuous flare-up capabilities of VKC that need careful attention.

The chemical entities of prednisolone, dexamethasone, fluorometholone, and Durezol (diflurprednate 0.05%, Alcon) would be acceptable. As a quick reminder, corticosteroids suppress the late phase reaction of allergic inflammation by inhibiting phospholipase A2 and reducing the formation of lipid-derived mediators from arachidonic acid.16

Take caution to mitigate the side effect profile of cataract formation, steroid-induced glaucoma, and herpetic disease. An alternative would be Lotemax (loteprednol 0.5%, Bausch + Lomb) to lessen these concerns. It has been inaccurately classified for years as a “soft” steroid due to the ester classification.17

Ocular Therapeutix is developing Dextenza (dexamethasone) as a punctal plug depot for slow release administration to alleviate post-surgical inflammation and pain.18 This would be a convenient and a fairly noninvasive use for treating VKC that shows potential with regard to increasing adherence of therapy.19

Related:

The last therapeutic class is immunomodulating agents that inhibit T-cell activation and eosinophilic infiltration into the conjunctiva. This class interferes with both late-phase and delayed-type allergic reactions.

In my clinic, I find great success with Restasis (cyclosporine 0.05%, Allergan), cyclosporine 2%(neoral, Novartis), or tacrolimus 0.03 percent (protopic, Astellas Pharma US, Inc.). Tacrolimus has been studied in a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial with tacrolimus 0.1 percent (protopic, Astellas Pharma US, Inc.) suspension in 56 patients with VKC/AKC refractory to conventional treatment. The results showed that tacrolimus caused marked improvement in objective signs and was well tolerated by patients.20

It is important to discuss with patients and document the conversation that these agents are all off-label for this condition and pediatric population.

Final Future Thoughts

The reality is that there are more chemical entities on the horizon in known classes such as humanized monoclonal antibodies or kinase inhibitors (Syk/JAK) to undiscovered entities. Consequently, there is no need to share tough love with a parent regarding the successful treatment and management of VKC.

Related:

References

1.Buckley RJ. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1988;28(4):303-308.

2. Kraus, Courtney. Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis. American Academy of Ophthalmology. April 28, 2016. Accessed January 20, 2017.

3. Barney NP (1997): Vernal and atopic keratoconjunctivitis. In: Krachmer JH, Mannis MJ & Holland EJ (eds). Cornea. St. Louis: Mosby, 811–817.

4. Leonardi A, Bogacka E, Fauquert JL, Kowalski ML, Groblewska A, Jedrzejczak-Czechowicz M, Doan S, Marmouz F, Demoly P, Delgado L. Ocular allergy: recognizing and diagnosing hypersensitivity disorders of the ocular surface. Allergy. 2012 Nov; 67(11):1327–37.

5. Bonini S, Bonini S, Lambiase A, Marchi S, Pasqualetti P, Zuccaro O, Rama P, Magrini L, Juhas T, Bucci MG. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis revisited. a case series of 195 patients with long-term followup. Ophthalmology. 2000 Jun;107(6):1157–63.

6. Diallo JS. Tropical endemic limboconjunctivitis. Rev Int Trach Pathol Ocul Trop Subtrop 1976;53(3-4):71–80.

7. Santos CI, Huang AJ, Abelson MB, Foster CS, Friedlaender M, McCulley JP. Efficacy of lodoxamide 0.1% ophthalmic solution in resolving corneal epitheliopathy associated with vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994 Apr 15;117(4):488-97.

8. Allansmith MR. The eye and immunology. St Louis. Mosby. 1982. Print.

9. Coombs RRA, Gell PGH. The classification of allergic reactions underlying disease. Clinical aspects of immunology. Oxford. Blackwell Scientific Publications. 1962. Print.

10. Johansson SG, Hourihane JO, Bousquet J, EAACI (European Academy of Allergology and Cinical Immunology) nomenclature task force, et al. A revised nomenclature for allergy: an EAACI position statement from the EAACI nomenclature task force. Allergy. 2001 Sept;56(9):813–24.

11. Leonardi A. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis: pathogenesis and treatment. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2002 May; 21(3): 319–39.

12. O’Shea JG. A survey of vernal keratoconjunctivitis and other eosinophil-mediated external eye diseases amongst Palestinians. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2000 Jun;7(2):149-57.

13. Bremond-Gignac D, Donadieu J, Leonardi A, et al. Prevalence of vernal keratoconjunctivitis: a rare disease? Br J Ophthalmol. 2008 Aug;92(8):1097-102.

14. Stiehm ER, Ochs HD, Winkelstein JA. Immunodeficiency disorders: General considerations. In: Immunologic disorders in infants and children. Philadelphia. Saunders 2004. p.423.

15. Berdy GJ, Smith LM, George MA, et al. The effects of disodium cromoglycate in the a human model of acute allergic conjunctivitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1989; 30(3 Suppl) :503.

16. Schleimer RP. Effects of glucocorticosteroids on inflammatory cells relevant to their therapeutic applications in asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990 Oct;10(10):933-7.

17. Druzgala P, Wu WM, Bodor N. Ocular absorption and distribution of loteprednol etabonate, a soft steroid, in rabbit eyes. Curr Eye Res. 1991;10(10):933.

18. McGrath M, Blizzard C, Desai A, et al. In vivo drug delivery of low solubility corticosteroids from bioresorbable hydrogel, punctum plugs. ARVO Annual Meeting Abstract. 2014 Apr.

19. Ocular Therapeutix. Dextenza. Available at:

20. Ohashi Y, Ebihara N, Fujishima H, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of tacrolimus ophthalmic suspension 0.1% in severe allergic conjunctivitis. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2010 Apr;26(2):165-73.

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.