How the Japanese treat allergic conjunctivitis

Michael Cooper, OD, takes a look at how the Japanese treat allergic conjunctivitis to gain a different perspective on treatments. What he finds is that we aren't so different after all.

As allergy season is about to kick into high gear, I thought it might be interesting to review how another country like Japan tackles ocular allergies. Like North America, there has been an exponential rise in sensitization by 2.6-fold from 1980 to 2000 due to the prevalence of Japanese cedar pollen (JCP, sugi-pollinosis).1

During the height of allergy season between February and April, a large number of patients with sugi-pollinosis experience more severe symptoms for longer periods of time compared to other pollen allergies. In this case, aerobiology might hold the explanation because JCP is dispersed in large quantities over long distances (>62 miles in some cases) and can remain airborne for more than 12 hours.2

Previously from Dr. Cooper: Substance P: Dry eye and allergy’s mixed signal or missing link?

Japanese cypress pollen is dispersed in April and May immediately after the release of JCP, causing a “sandwiching” effect of pollen exposure. This cross reactivity has allowed an elongation of the allergy season in many parts of Japan with annual climate variations leading to healthcare problems that affect daily activity, work productivity, learning, sleep, and quality of life (QOL) in people of all ages.3

What’s in a number?

In 1993, the Allergy Integrated Project Epidemiologic Investigation Group of the Ministry of Health and Welfare surveyed the entire Japanese population. Researchers found the proportion of people with bilateral ocular itching at 16.1 percent in children under age 15 and 21.1 percent in adults.4

The proportion of people with allergic conjunctival diseases diagnosed by ophthalmologists was 12.2 percent in children and 14.8 percent in adults.4 From these results, the proportion of people with allergic conjunctival diseases in the entire Japanese population is estimated to be 15 to 20 percent. If this statistic sounds familiar, you would be right because the U.S. figure is the same on a macroscale.5,6

Related: How to combat vernal keratoconjunctivitis

A research group on allergic ocular disease of the Japan Ophthalmologists Association conducted epidemiologic surveys of all patients with allergic conjunctival diseases who were treated across Japan in 28 different facilities from January 1, 1993, to December 31, 1995. Researchers found female patients with seasonal and perennial allergic conjunctivitis (SAC or PAC) outnumbered male patients 2-to-1, whereas male patients with vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) outnumbered female patients 2-to-1.7

Getting treatment results

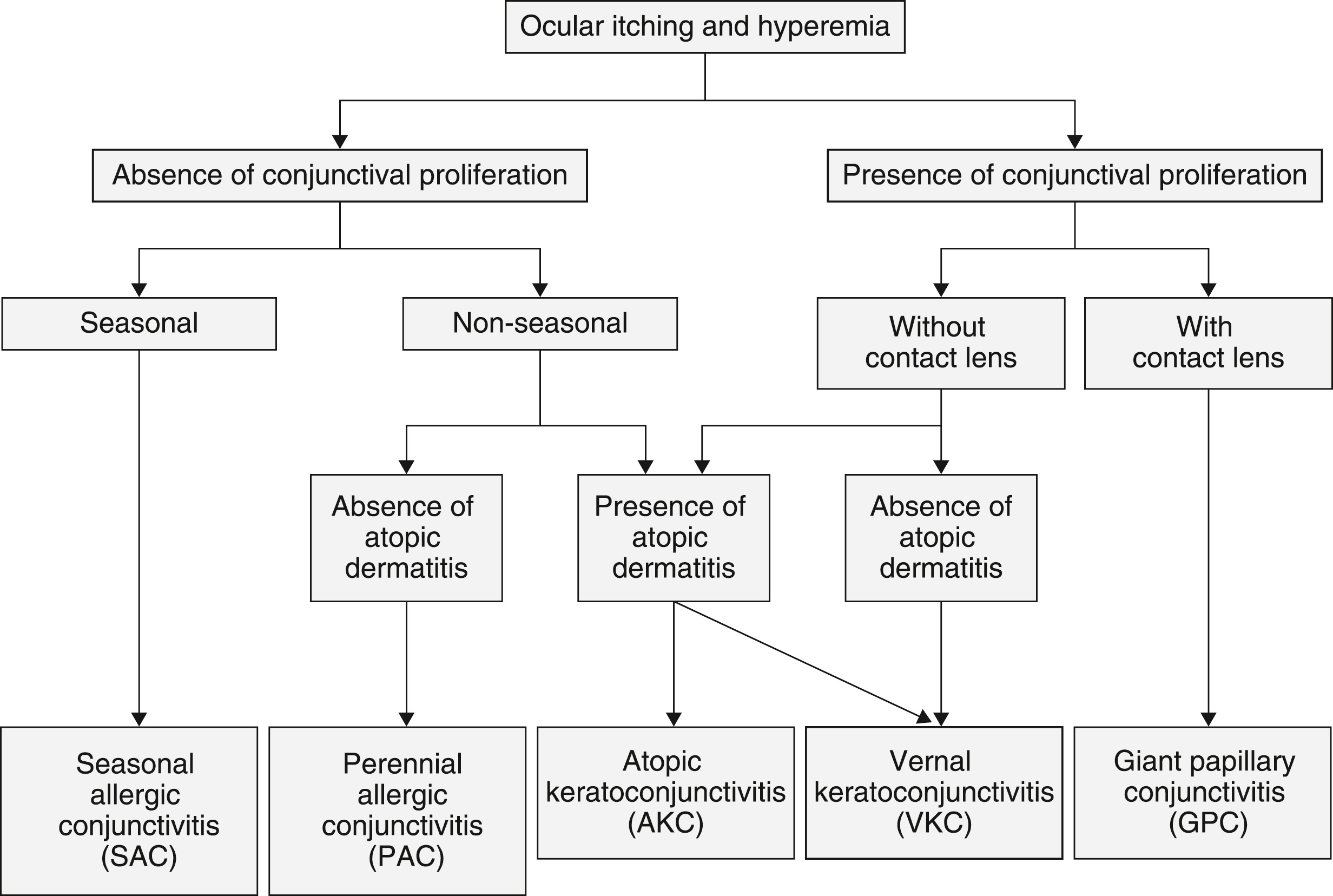

Although the Japanese classification system bears resemblance to how ophthalmology and optometry bracket these disease states in the U.S., the treatment patterns illustrate divergence likely due to drug availability and guidelines.8

Table 1.

As with any management paradigm, therapeutics precedes surgical intervention to minimize the risk profile.

Related: The increasing role of climate, hygiene, and aerobiology in allergy

The medical decision path from mast cell, to antihistamine H1 antagonists/combinations, to steroid application remains the same no matter where you reside (Table 1).4 In managing pediatric patients or those with corneal epithelial defects from vernal or atopic keratoconjunctivitis, oral medication is dispensed with a one- to two-week follow-up and close communication among ophthalmology, internists, and pediatricians to watch for side effects.

The course of action diverges when handling recalcitrant cases in which these therapeutic remedies are not exerting the desired effect. When this situation arises, subtarsal conjunctival steroid injections of triamcinolone acetonide or betamethasone are administered to the upper eyelid for intractable or severe cases with cautionary notes to follow carefully for intraocular pressure elevation or repeated use in children under age 10.9,10

While cyclosporine (Papilock 0.1 percent, Santen Pharmaceutical Co.) solution and tacrolimus (Talymus 0.1 percent, Senju Pharmaceutical Co.) suspension are reserved for experimental literature work and off-label clinical usage, Japan has approved these agents for VKC treatment to reduce the need for long-term steroid use.11

Further surgical management is warranted when symptoms are not alleviated by drug treatment and/or conjunctival papillary hyperplasia progresses, causing refractory corneal epithelium disorder. The procedure performed is a tarsal conjunctival resection including the papillae to reduce the mechanical and biological burden on the ocular surface.4 Even though the treatment result is immediate, there can be recurrence of conjunctival papillary hyperplasia in some cases.

U.S. is no different

Treatment and management methodology in Japan do not digress tremendously from the American Academy of Ophthalmology preferred practice guidelines for conjunctivitis.12

The moral of the story is we are not so different after all.

References

1. Kaneko, Y., Motohashi, Y., Nakamura, H., Endo T, Eboshida A. Increasing Prevalence of Japanese Cedar Pollinosis: A Meta-Regression Analysis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2005; 136:365–371.

2. Okamoto Y, Horiguchi S, Yamamoto H, Yonekura S, Hanazawa T. Present situation of cedar pollinosis in Japan and its immune responses. Allergol Int. 2009; Jun 58(2): 155–162.

3. Makihara S, Okano M, Fujiwara T, Kimura M, Higaki T, Haruna T, Noda Y, Kanai K, Kariya S, Nishizaki K. Early interventional treatment with intranasal mometasone furoate in Japanese cedar/cypress pollinosis: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Allergol Int. 2012 Jun;61(2):295-304.

4. Takamura E, Uchio E, Ebihara N, Ohno S, Ohashi Y, Okamoto S, Kumagai N, Satake Y, Shoji J, Nakagawa Y, Namba K, Fukagawa K, Fukushima A, Fujishima H; Japanese Society of Allergology. Japanese guidelines for allergic conjunctival diseases 2017. Allergol Int. 2017 Apr;66(2):220-229.

5. Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America. Allergy Facts and Figures. Available at: http://www.aafa.org/display.cfm?id=9&sub=30. Accessed 1/10/18.

6. Cooper MS. 3 Tips for Discussing Allergy with Kids. Optometry Times. Available at: http://optometrytimes.modernmedicine.com/optometrytimes/news/3-tips-navigate-allergy-discussion-kids?page=full. Accessed 1/10/18.

7. Japanese Ocular Allergology Society. [Guidelines for the clinical management of allergic conjunctival disease (2nd edition)]. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 2010 Oct;114(10):831-70.

8. Ohno S, Uchio E, Ishizaki M, et al. [New clinical evaluation standard and seriousness classification of allergic conjunctival diseases]. Iyaku Journal [Medicine & Drug Journal]. 2001; 37:1341–1349. (in Japanese).

9. Kumar S. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis: a major review. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009 Mar;87(2):133-47.

10. De Smedt S, Wildner G, Kestelyn P. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis: an update. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013 Jan;97(1):9-14.

11. Ohashi Y, Ebihara N, Fujishima H, Fukushima A, Kumagai N, Nakagawa Y, Namba K, Okamoto S, Shoji J, Takamura E, Hayashi K. A randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of tacrolimus ophthalmic suspension 0.1% in severe allergic conjunctivitis. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2010 Apr; 26(2):165–174. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2010 Apr;26(2):165-74.

12. AAO Cornea/External Disease PPP Panel, Hoskins Center for Quality Eye Care. Conjunctivitis PPP - 2013. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Available at: https://www.aao.org/preferred-practice-pattern/conjunctivitis-ppp--2013. Accessed 1/10/17.

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.