How point-of-care diagnostic lab tests help clinical decisions

Point-of-care (POC) diagnostic laboratory testing is not common in eye care. This is not due to any lack of clinical need-it is rather the result of a lack of specific tests known to demonstrate diagnostic and/or treatment relevance to the optometrist and a general resistance to adopting new diagnostic technologies.

Point-of-care (POC) diagnostic laboratory testing is not common in eye care. This is not due to any lack of clinical need-it is rather the result of a lack of specific tests known to demonstrate diagnostic and/or treatment relevance to the optometrist and a general resistance to adopting new diagnostic technologies. Yet there is evidence of a rapidly growing acceptance of POC testing as clinicians begin to better understand the diagnostic and treatment value of currently available tests and how they correlate to various ocular surface disorders.1

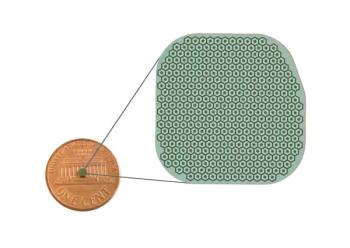

Quantitative or qualitative ophthalmic lab tests are quite precise when used as diagnostic tools. They may also be used to evaluate treatment efficacy. Whether they are based on traditional lateral flow immunoassay systems, electrochemical sensors, or other platforms under development, continued advances in technology have steadily produced more sophisticated devices capable of accurately measuring an increasing number of target ocular analytes.

More from this issue:

POC lab tests have the real potential to streamline health care in general and improve clinical outcomes. In the ophthalmic clinic, for example, the transfer from physician diagnostic chair time to lab tech time is itself a significant improvement in patient flow. The more testing the technician is able to perform, the better for overall office flow-the clinician is able to spend more time with the patient instead of performing tests. Imagine the improvement in patient flow if a patient’s lab test results are in the chart before the doctor enters the lane.

In my experience, the use of POC lab testing within optometry is growing, and it will continue to expand as more tests are developed and more clinicians adopt them in their day-to-day diagnostic regimen. There has been a slow but steady shift over the past 20 years from such tests considered as interesting gadgets to becoming critical diagnostic systems.

Medical necessity as guiding principle

We must begin by stating that the use of lab tests, particularly those that are reimbursable, are governed by one basic premise; they must be judged to be medically necessary.2 As health maintenance organizations (HMOs) and government agencies seek to provide quality cost-effective medicine, reduction in the ordering of “unnecessary” laboratory tests are one of their favorite objects of pursuit.

In this regard, the critical question facing physicians is: What constitutes a necessary laboratory test? Medical necessity is defined as diagnosing and treating an illness or injury. The patient’s documented signs, symptoms, or diagnosis must support the services or treatment in order to be considered medically necessary.3 It is incumbent upon physicians to understand which laboratory tests are accurate enough to be clinically useful and appropriate to order in the diagnosis and follow-up of a patient’s medical condition.4

Evaluating diagnostic performance

Many physicians didn’t learn much in their educations about laboratory medicine.

According to Michael Laposata, MD, PhD, executive vice-chair of pathology, microbiology, and immunology at Vanderbilt University, “The importance of understanding the principles for selecting and ordering the most rational laboratory test(s) on a specific patient is heightened in the current age of managed care, medical necessity, and outcome-oriented medicine.”5

More from this issue:

The ability to understand a lab test’s diagnostic performance characteristics, or its ability to provide clinically consistent and relevant data, is critical for meaningful clinical use. If a test has poor performance characteristics, exactly how poor is it? If a test is good, how good is it? How would one know?

Four indicators are most commonly used to determine the reliability of all clinical lab tests. Two of these, accuracy and precision, reflect how well the test method performs day to day in a laboratory. The other two, sensitivity and specificity, address with how well the tests are designed to distinguish disease from the absence of disease.6

The accuracy and precision of each test are established and frequently monitored by the clinic’s lab director. Sensitivity and specificity are determined by research studies and are generally found in the manufacturer’s published literature. Although each test has its own performance measures and appropriate uses, laboratory tests are designed to be as precise, accurate, specific, and sensitive as possible. A definition of each term follows.

Precision. A test method is said to be precise when repeated analyses on the same sample give similar results or the amount of random variation is small.

More from this issue:

Accuracy. A test method is said to be accurate when the test value approaches the absolute “true” value of the substance (analyte) being measured. Routinely, performed tests are compared to known “control specimens” and evaluated. Although a test that is 100 percent accurate and 100 percent precise is ideal, in practice, test methodology, instrumentation, and laboratory operations all contribute to small but measurable variations in results.

The difference between a known standard and multiple test average results is known as the coefficient of variation (CV).7 The CV also provides a general “feeling” about the performance of a method or test. Generally, CVs of 5 percent or less give us the feeling of good method performance, whereas CVs or 10 percent or more are likely less accurate. However, there are exceptions to the rule. For example, when measuring analytes at very low concentrations, the CV may be very high (over 20 percent) but accurate and reliable for clinical use.

Sensitivity. Sensitivity is the ability of a test to correctly identify individuals who have a given condition.8 In other words, if a person has a disease, how often will the test be positive (true positive rate)? For example, a certain test may prove to be 90 percent sensitive. If 100 patients are known to have a certain condition, a test that identifies that condition will correctly do so for 90 of those 100 cases (90 percent). Generally, the more sensitive a test, the fewer false-negatives will be produced. Put another way, if the test is highly sensitive and the test result is negative, you can be nearly certain the patient doesn’t have the disease.

Specificity. Specificity is the ability of a test to correctly exclude individuals who do not have a given condition.8 Or, if a person does not have the disease, how often will the test be negative (the true negative rate)? For example, a certain test may prove to be 90 percent specific. If 100 healthy individuals are tested, only 90 of those 100 healthy patients (90 percent will be found “normal” or free of the target disease. In general, the more specific a test, the fewer false-positive results will be produced. If the test result for a highly specific test is positive, you can be nearly certain the patient actually has the disease.

More from this issue:

The primary metrics that are most important to the end user are those representing the quality and predictive value of the tests being performed, sensitivity and specificity. Secondarily, test accuracy and precision may decline, thus becoming less predictive, if lab personnel do not carefully follow recommended test procedures and protocols. Therefore, it is important for each party, the manufacturer and the ophthalmic lab, to work together in an effort to produce the highest level of accuracy possible.

Clinical performance of ophthalmic POC tests

The clinical need for accurate and precise tear-based ophthalmic diagnostic lab tests is no less important than those in general medicine using blood, serum, or any other sample source. Because the clinical performance of all laboratory tests differ with respect to their diagnostic accuracy (i.e., sensitivity and specificity), the selection of the appropriate test will vary depending on the purpose for which the test is used. One can assess the clinical performance characteristics of any lab test by reviewing published data relative to sensitivity and specificity.

To date, the FDA has approved five ocular POC diagnostic lab tests that use tears as the source material.

• Ocular lactorferrin, TearScan (Advanced Tear Diagnostics), Class II CLIA

• Ocular IgE, Tear Scan (Advanced Tear Diagnostics), Class II CLIA

• Ocular osmolarity, TearLab Osmolarity System (TearLab), Class I CLIA

• Ocular adenovirus, AdenoPlus (RPS), Class I CLIA

• Ocular MMP-9, InflammaDry (RPS), Class I CLIA

Tests with CLIA Class I designation are waived, while Class II is moderate. CLIA information

For reference, it is important to note that any test with a sensitivity of 50 percent and a specificity of 50 percent is no better than a coin toss in deciding whether a disease or condition may be present. For lab data to be useful, it must be dependably accurate.

According to Professor Frank Wians, PhD, in the department of pathology at the University of Texas, “Tests possessing a combined sensitivity and specificity equal to 170 or greater are likely to prove clinically useful, thus a lab test with a sensitivity of 95 percent and a specificity of 95 percent (sum=190) should be considered an excellent test.”5

By comparison, a test with 60 percent sensitivity and 70 percent specificity (sum=130) would be of marginal clinical utility and subpar for routine clinical use.

More from this issue:

Table 1 provides a comparative overview of the various performance characteristics of each tear-based test currently on the market.

In Table 1, there is reference to positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV). These are interesting but seldom used performance metrics when assessing the overall clinical performance of diagnostic lab tests.

PPV is defined as the proportion of all positive test results (true positives + false positives) to true positives.13 It is calculated using the following formula:

PPV=true positives/(true positives + false positives)

NPV is defined as the proportion of all negative test results (true negatives + false negatives) to true negatives.13 It is calculated using the following formula:

NPV=true negatives/(true negatives + false negatives)

PPV and NPV performance results depend, in large measure, on the size of the patient population being analyzed. As with any statistical method, the results are susceptible to skewing. For the clinical ophthalmic physician, it is safe to assume the most important lab test performance metrics are those presenting a test’s ability to confirm or rule out the presence or absence of a target condition-sensitivity and specificity.

Regulatory requirements for tear testing

All diagnostic lab tests are regulated by the FDA and managed by Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment (CLIA). CLIA is the federal regulatory body which sets training and operating standards and issues certificates for all clinical laboratory testing that use human specimens for the purpose of providing information used to diagnose, prevent, or treat. CLIA’s objective is to ensure the accuracy, reliability, and timeliness of lab test results regardless of where performed.14 All CLIA enforcement responsibilities fall to each state’s Department of Health.

Currently, all licensed optometrists and ophthalmologists meet the federal CLIA requirements needed to perform Class I (waived) and Class II (moderate complexity) lab tests as long as these tests use tears as the source material. Several states still restrict or prohibit optometrists from performing Class I and/or Class II lab tests in their offices, most notably California and New York.

Of the five ocular POC diagnostic lab tests that use tears, TearScan lactoferrin and IgE tests are Class I, while the remaining three are Class II.

The CLIA application process is simple and takes about six weeks to receive a provider number. Once this number has been issued, testing may be performed.

All FDA-approved tear tests have been authorized for diagnostic use but are, in practice, limited by medical and reimbursement policies to being performed only on patients having specific complains or exhibiting signs and symptoms. None are currently approved for “general screening” purposes.

All tests mentioned above have been approved for reimbursement by federal healthcare programs and most, if not all, private payers. See Table 2 for a brief overview of relevant CPT codes as well as 2016 CMS reimbursement averages.15

Putting POC into your practice

It is important for all clinicians to recognize that laboratory data, although extremely useful in diagnostic decision-making, is only as good as its ability to provide precise and accurate results. Tests should be used as an aid and adjunct to the totality of the patient’s relevant findings (e.g., history, physical exam, etc.). Laboratory data is never a substitute for a good physical exam and patient history. Clinicians should treat the patient, not the laboratory results.

Effective treatment follows an accurate diagnosis. To the extent that lab tests are beginning to play an increasing role in the ophthalmic diagnostic process, it remains important for the optometric physician to better understand the clinical utility and performance characteristics of any test they intend to use on their patients. These tests provide useful data that can only aid in the diagnosis and management of our patients and make us better clinicians.

References

1. Sambursky R, Davitt WF 3rd, Friedburg M, et al. Prospective, multicenter, clinical evaluation of point-of-care matrix metalloproteinase-9 test for confirming dry eye disease. Cornea. 2014 Aug;33(8):812-8.

2. Schimke I. Quality and timeliness in medical laboratory testing. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2009 Mar;393(5):1499-504.

3. Pesso R. Blog: Medical necessity, labs tests, & CMS. North American Partners in Anesthesia. Available at:

4. Pecoraro V, Germagnoli L, Banfi G. Point-of-care testing: where is the evidence? A systematic survey. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2014 Mar; 52 (3): 313-324.

5. Wians FH Jr. Clinical laboratory tests: which, why, and what do the results mean? Lab Med. 2009 Feb; 40(2):105-113.

6. American Association for Clinical Chemistry. How reliable is laboratory testing? Available at:

7. Reed GF, Lynn F, Meade BD. Use of coefficient of variation in assessing variability of quantitative assays. Clin Diag Lab Immunol. 2002 Nov; 9(6):1235-9.

8. Williams MV. Statistical definitions. Emory University School of Medicine. Available at:

9. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 510(k) substantial equivalence determination decision summary. Advanced Tear Diagnostics. Available at:.

10. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 510(k) substantial equivalence determination decision summary. TearLab Osmolarity System. Available at:

11. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 510k for RPS Adeno Detector Plus. Available at:

12. Sambursky R, Davitt WF 3rd, Latkany R, Tauber S, Starr C, Friedberg M, Dirks MS, McDonald M. Sensitivity and specificity of a point-of-care matrix metalloproteinase 9 immunoassay for diagnosing inflammation related to dry eye. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013 Jan; 131(1):24-28.

13. Felson D. Positive and negative predictive value. Boston University School of Public Health. Available at: http://sphweb.bumc.bu.edu/otlt/MPH-Modules/EP/EP713_Screening/EP713_Screening5.html. Accessed 12/10/15.

14. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Clinical laboratory improvement amendments (CLIA). Available at:

15. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2015 CMS Clinical Laboratory fee schedule. Available at:

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.