New treatments and surgeries are transforming the glaucoma landscape

Advancements in medications and lasers bring better adherence and outcomes.

As the most common cause of irreversible blindness worldwide, glaucomatous optic neuropathy is well known to optometrists, and clinicians are comfortable diagnosing and managing it.

For years, the standard algorithm has changed little: treat patients with topical medications until the disease becomes severe enough to consider incisional surgery.

In the past decade, however, this strategy has been dramatically upended by the introduction of several new medications, a new understanding of the role of lasers, and the rapid growth of low-risk microsurgeries.

Although the diagnosis of glaucoma has only advanced modestly in recent years, the management of the disease has undergone a transformation. In particular, management has shifted toward intervention that is earlier, safer, and often more surgical.

This 2-part series will review the new landscape of glaucoma management: part 1 will cover new medications and the use of lasers, and part 2 will focus on the minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS).

Approach to management

Glaucoma is a chronic progressive optic neuropathy that causes irreversible peripheral and/or central vision loss and may ultimately lead to blindness.

Approximately 76 million individuals have glaucoma worldwide, a number that will increase over the next 2 decades.1 Risk factors for glaucoma include older age, a family history of glaucoma, non-White race, thinner corneas, and elevated intraocular pressure (IOP).2

Related: Podcast: Mark Dunbar, OD, FAAO dives into glaucoma, part 1

There are many subtypes of glaucoma, a topic beyond the scope of this article. The only modifiable risk factor for most subtypes is elevated IOP, and almost all existing treatments are aimed at lowering IOP.

Glaucoma management is notoriously difficult to standardize, and treatment decisions are highly personal to each patient. Many factors must be considered, including pretreatment IOP, the severity of glaucomatous damage, the rate of progression, and the patient’s life expectancy.

Generally, a more aggressive treatment is recommended for younger individuals, those with severe disease or a fast rate of progression, those with low unmanaged IOP, and those with additional risk factors.

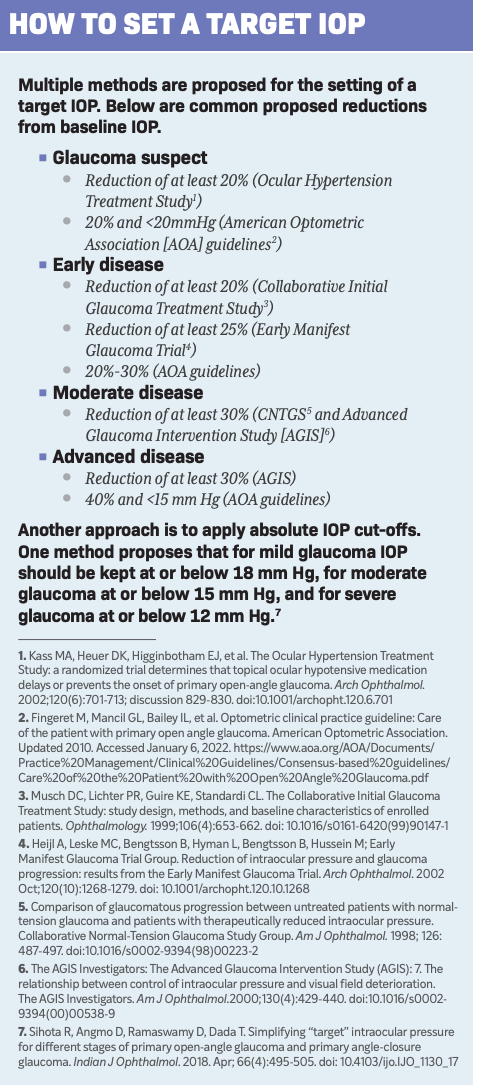

Many doctors choose to set a target IOP for each eye; this number can then guide treatment, as it is considered to be the highest acceptable IOP that is still likely to prevent or slow further vision loss.3

Target IOP can be determined based on a percentage reduction from pretreatment IOP or on the stage of glaucoma (Sidebar: How to set a target IOP).

Selective laser trabeculoplasty

As the glaucoma armamentarium becomes more varied and powerful, many doctors are realizing that improving patient care means managing glaucoma sooner and more safely but also more aggressively. Selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) illustrates this point.

SLT is a 532-nm Q-switched, frequency-doubled neodymium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Nd:YAG) laser that delivers very short pulses of energy to pigmented trabecular meshwork (TM) cells.

Related: Beyond anxiety in patients with glaucoma

No structural or coagulative damage has been found in the TM after treatment, the procedure is painless, and it results on average in a decline in IOP of 17% to 30%. SLT is indicated for mild to moderate cases of open angle, pigment dispersion, or pseudoexfoliative glaucoma.4

Since the introduction of SLT in 2001, doctors in the US have tended to regard the use of SLT as a secondary attempt after maximum drop therapy has failed, usually just before incisional surgery becomes necessary.

This changed recently with the publication of the LiGHT study (NCT03395535) in 2019, in which investigators showed definitively that SLT was superior to topical medications in efficacy, safety, and cost, and strongly recommended considering SLT before starting any drops.5

As the conclusions of this landmark study reverberate through the profession, optometrists and ophthalmologists have adjusted their treatment algorithm. A diagnosis of glaucoma now frequently triggers using SLT first, instead of topical medications.

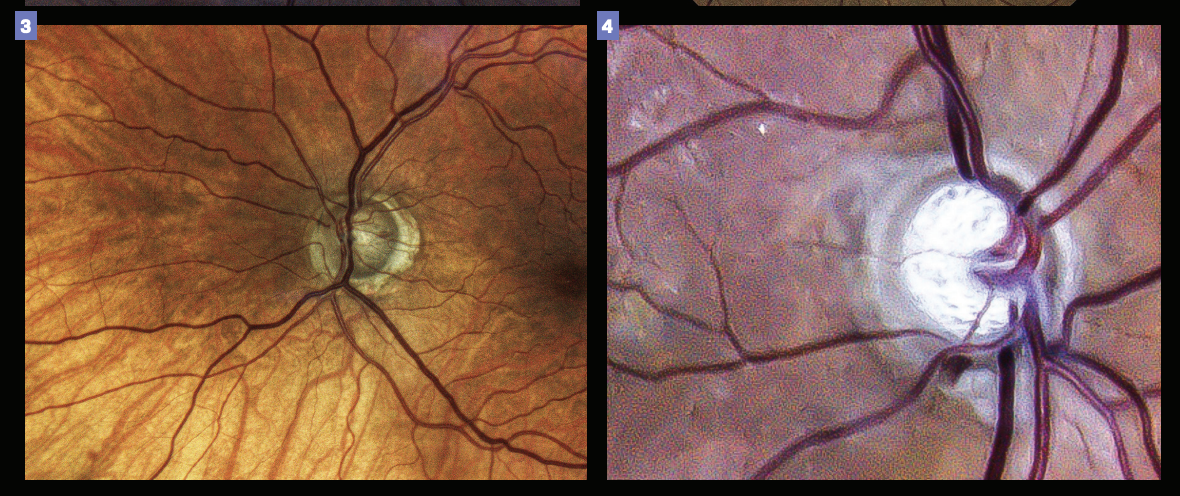

Figure 1. Severe thinning of the optic nerve. Glaucoma has reached the severe stage at this point, likely requiring a low IOP target. (Image courtesy of Gleb Sukhovolskiy, OD)

Figure 2. Large optic disk cupping. (Image courtesy of Aaron Bronner, OD)

Patient satisfaction with SLT is higher than with drops, and adherence is no longer an issue. SLT can be repeated as frequently as needed, and repeated SLT often results in greater effectiveness.6

Interestingly, investigators have uncovered suggestions that the current protocol of maximum-power SLT performed as needed might be inferior to low-power SLT performed annually.7 This inquiry has given rise to a large clinical trial whose results, once released, might change once again the use of this therapy.8

Topical medications

Historically, topical medications have been considered the first-line treatment for patients with glaucoma. There are now 5 major categories of IOP-lowering eye drops: prostaglandin analogues, ρ-kinase inhibitors, β-blockers, α-agonists, and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors.

Related: How one OD encouraged glaucoma medication adherence

Prostaglandin analogues (PGAs) reduce IOP by decreasing outflow resistance within the uveoscleral pathway. PGAs have been the first-line drops for many years, and despite the recent introduction of several more potent medications, they maintain that status due to their effectiveness, once-daily dosing, affordability, and low risk of adverse effects.

The use of PGAs has been correlated with a decrease in the number of trabeculectomies performed.9 PGAs commonly produce a 25% to 33% reduction in IOP, although the effect is more pronounced in patients with higher baseline IOPs.10 The PGAs can produce adverse effects of hyperemia, hypertrichosis, and periorbital fat atrophy.11

The new hypotensives

The FDA recently approved 3 new glaucoma topical medications that have had a large impact on prescribing patterns. The first of these, latanoprostene bunod (Vyzulta, Bausch + Lomb), was released in 2017. Latanoprostene bunod combines the known agent latanoprost with nitric oxide.

Figure 3. Presence of an optic disk hemorrhage could indicate future progression. Figure 4. Such risk of future disease progression may indicate the need for a more aggressive treatment. (Images courtesy of Gleb Sukhovolskiy, OD)

Nitric oxide increases aqueous outflow by relaxing chronic TM contraction. This provides an IOP reduction of 1 to 2 mmHg more than a PGA alone while maintaining the same dosing schedule.12

Netarsudil 0.2% (Rhopressa, Aerie Pharmaceuticals), a ρ-kinase (ROCK) inhibitor, also was introduced in 2017. The ρ-kinase enzyme promotes contraction of TM cells and matrix, so inhibition of the enzyme by this drug increases the outflow of aqueous fluid through the TM.

The use of netarsudil produces conjunctival hyperemia in 50% of patients—a significant adverse effect. Like the PGAs, Netarsudil is dosed once daily at bedtime. On average, it results in a 25% to 30% drop from baseline IOP.13

Related: What’s new in glaucoma medications

Netarsudil has been combined with latanoprost to create Rocklatan (Aerie), an effective combination medication. Rocklatan offers the highest average IOP reduction of any single glaucoma medication: 30% to 36% from baseline.14,15

The instillation regimen is identical to the PGAs, latanoprostene bunod, and netarsudil: once daily at bedtime. It is important to discuss the significant adverse effects of conjunctival hyperemia and corneal verticillata prior to starting this drop, in addition to the adverse effects linked to the latanoprost moiety.16

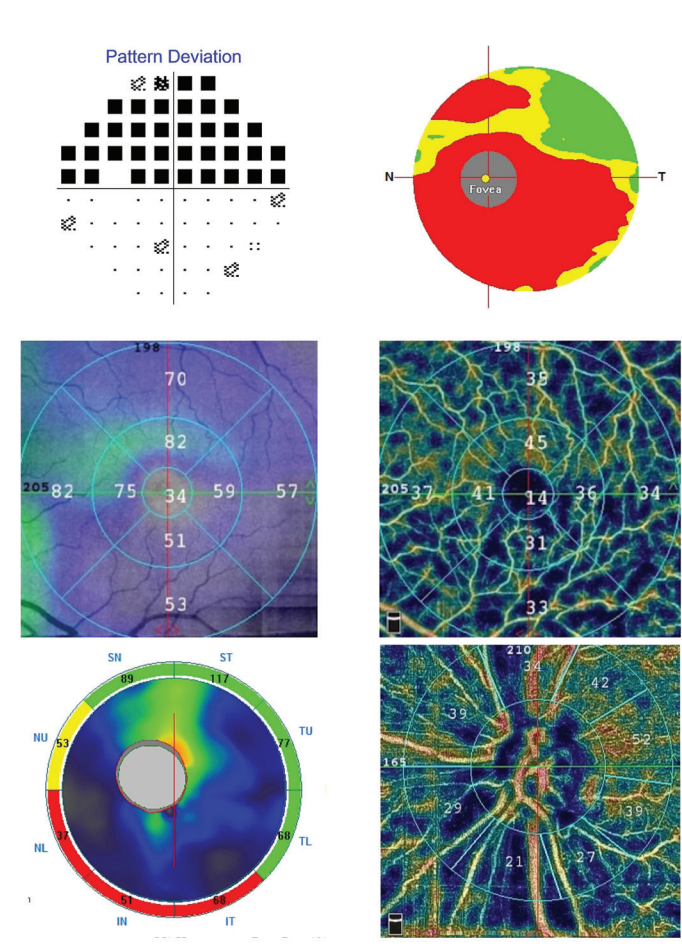

Figure 5. Superior visual fi eld defect correlates well with inferior thinning on nerve fi ber analysis and ganglion cell complex. Decreased vessel density follows the same pattern.

The introduction of netarsudil and nitric oxide has affected the treatment algorithm significantly. Whereas many doctors continue to start any topical therapy with a PGA, if this drug proves insufficiently potent, they may consider switching to Vyzulta or Rocklatan.

The instillation burden for these medications is no greater than that of the original PGA, and most patients will see a further reduction in their IOPs.

The traditional hypotensives

Older topical medications can still play a helpful role in the reduction of IOP. These include β-blockers, α-agonists, and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors.

By decreasing aqueous production, β-blockers reduce IOP. They are less likely to cause ocular surface issues; however, cardiac or respiratory adverse effects may occur.17 These should be avoided in patients with bradycardia, hypotension, asthma, and obstructive pulmonary disease.18 Patients who are already using systemic β-blockers should be carefully monitored when taking topical β-blockers.

Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors and α-agonists are commonly used second-line agents. These can be added to a patient’s regimen when a monotherapy is not sufficient. The α-agonists frequently cause conjunctival hyperemia.

Unfortunately, increasing the number of drops used daily negatively affects patient adherence to therapy.19 According to some studies, fewer than 50% of patients continue adhering to therapy beyond the first year.20

Related: Look beyond IOP in treating glaucoma patients

Combination therapies may help patient adherence and reduce exposure to preservatives. In cases of more severe disease and when a significant decrease in IOP is needed, a combination drop is preferred, as it will simplify the administration schedule and provide greater IOP reduction.

The list of combination drops available in the US includes timolol plus brimonidine (Combigan, Allergan), timolol plus dorzolamide (Cosopt/Cosopt PF, Akorn), brimonidine plus brinzolamide (Simbrinza, Alcon), and Rocklatan.

How to eliminate nonadherence

The largest factor interfering with the success of medical glaucoma treatment is patient inability to adhere to topical therapy as prescribed.21,22 Challenges with drop adherence include difficulty with drop administration, adverse effects, and the expense of medications.

Thorough patient education regarding the severity and permanence of potential vision loss might seem like a powerful way to address poor adherence but is actually surprisingly ineffective.23

It may not be the lack of education that precludes patients from taking their glaucoma medication, but rather various aspects of their lifestyles, such as level of busyness, time away from home, or forgetfulness.24

This is supported by the fact that younger patients have higher nonadherence rates, despite having better access to information about glaucoma.25

Medications with the easiest administration, such as once-daily regimens, should be strongly considered as first line treatments. The more complex the medication regimen, the lower the rate of adherence to therapy.26

Utilizing treatment modalities that are not reliant on constant patient cooperation will result in better continuity of care. This includes SLT, surgeries, and sustained-release implants.

Related: What’s new in glaucoma medications

Sustained-release medications may soon become a highly effective option for managing glaucoma. The only device approved for use at this point is the bimatoprost intracameral implant Durysta (Allergan).

The solid, biodegradable, rod-shaped implant is placed in the anterior chamber angle and then slowly releases a prostaglandin analog as its copolymer matrix degrades. The intracameral implant is capable of delivering medication for up to 6 months but is not yet approved for repeat use.27

A new paradigm

We are in the midst of a paradigm shift in the management of glaucoma. Our management of this disease has shifted towards intervention that is earlier, safer, and often more surgical.

We now know that a large proportion of patients do not use their eye drops as prescribed, and the wave of new once-daily drops and the increased use of SLT laser as a first-line treatment are powerful strategies to produce more consistent results.

Another powerful strategy has been the increased use of MIGS, which will be treated in the second part of this 2-part series.

The field of glaucoma has recently become significantly more exciting, and is evolving quickly. As optometrists master the new options, we will be able to offer our patients a higher standard of care, which can result in significantly less vision lost to this disease.

See more on glaucoma

--

References

1. Tham YC, Li X, Wong TY, Quigley HA, Aung T, Cheng CY. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(11):2081-2090. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.05.013

2. Hollands H, Johnson D, Hollands S, Simel DL, Jinapriya D, Sharma S. Do findings on routine examination identify patients at risk for primary open-angle glaucoma? JAMA. 2013;309(19):2035-2042. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.5099

3. Villasana GA, Bradley C, Ramulu P, Unberath M, Yohannan J. The effect of achieving target intraocular pressure on visual field worsening. Ophthalmology. Published online September 8, 2021. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.08.025

4. Leahy KE, White AJR. Selective laser trabeculoplasty: current perspectives. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;9:833-841. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S53490

5. Gazzard G, Konstantakopoulou E, Garway-Heath D, et al. Selective laser trabeculoplasty versus eye drops for first-line treatment of ocular hypertension and glaucoma (LiGHT): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10180):1505-1516. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32213-X

6. Garg A, Vickerstaff V, Nathwani N, et al. Efficacy of repeat selective laser trabeculoplasty in medication-naïve open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension during the LiGHT trial. Ophthalmology. 2020;127:467-476. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.10.023

7. Gandolfi SA, Ungaro N, Varan I, Saccà S. Low power selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) repeated yearly as primary treatment in open angle glaucoma: long-term comparison with conventional SLT and ALT. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59:3459.

8. Realini T, Gazzard G, Latina M, Kass M. Low-energy selective laser trabeculoplasty repeated annually: rationale for the COAST trial. J Glaucoma. 2021;30(7):545-551. doi:10.1097/IJG.0000000000001788

9. Rachmiel R, Trope GE, Chipman ML, Gouws P, Buys YM. Effect of medical therapy on glaucoma filtration surgery rates in Ontario. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124(10):1472-1477. doi:10.1001/archopht.124.10.1472

10. Aspberg J, Heijl A, Johannesson G, et al. Intraocular pressure lowering effect of latanoprost as first-line treatment for glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2018;27(11):976-980. doi:10.1097/IJG.0000000000001055

11. Alm A. Latanoprost in the treatment of glaucoma. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:1967-1985. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S59162

12. Weinreb RN, Ong T, Sforzolini S, et al; VOYAGER Study Group. A randomised, controlled comparison of latanoprostene bunod and latanoprost 0.005% in the treatment of ocular hypertension and open angle glaucoma: the VOYAGER study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99(6):738-745. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-305908

13. Serle JB, Katz LJ, McLaurin E, et al; ROCKET-1 and ROCKET-2 Study Groups. Two phase 3 clinical trials comparing the safety and efficacy of netarsudil to timolol in patients with elevated intraocular pressure: rho kinase elevated IOP treatment trial 1 and 2 (ROCKET-1 and ROCKET-2). Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;186:116-27. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2017.11.019

14. Asrani S, Robin AL, Serle JB, et al. Netarsudil/latanoprost fixed-dose combination for elevated intraocular pressure: 3-month data from a randomized phase 3 trial. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;S0002-9394:30284–3.

15. Walters TR, Ahmed IIK, Lewis RA, et al. Once-daily netarsudil/latanoprost fixed-dose combination for elevated intraocular pressure in the randomized phase 3 MERCURY-2 study. Ophthalmol Glaucoma. 2019;2(5):280-289. doi:10.1016/j.ogla.2019.03.007

16. Radell JE, Serle JB. Netarsudil/latanoprost fixed-dose combination for the treatment of open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Drugs Today (Barcelona). 2019;55(9):563-574. doi:10.1358/dot.2019.55.9.3039670

17. Lee DA, Higginbotham EJ. Glaucoma and its treatment: a review. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2005;62(7):691-699. doi:10.1093/ajhp/62.7.691

18. Stein JD, Khawaja AP, Weizer JS. Glaucoma in adults–screening, diagnosis, and management: a review. JAMA. 2021;325(2):164-174. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.21899

19. Holló G, Topouzis F, Fechtner RD. Fixed combination intraocular pressure-lowering therapy for glaucoma and ocular hypertension: advantages in clinical practice. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2014;15:1737-1747. 10.1517/14656566.2014.936850

20. Schwartz GF, Quigley HA. Adherence and persistence with glaucoma therapy. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008;53(suppl 1):S57-S68. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2008.08.002

21. Robin AL, Muir KW. Medication adherence in patients with ocular hypertension or glaucoma. Expert Rev Ophthalmol. 2019;14(4-5):199-210. doi:10.1080/17469899.2019.1635456

22. Nordstrom BL, Friedman DS, Mozaffari E, Quigley HA, Walker AM. Persistence and adherence with topical glaucoma therapy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(4):598-606. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2005.04.051

23. Fiscella R, Caplan E, Kamble P, et al. The effect of an educational intervention on adherence to intraocular pressure-lowering medications in a large cohort of older adults with glaucoma. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24(12):1-11. doi:18553/jmcp.2018.17465.

24. Anbesse DH, Yibekal BT, Assefa NL. Adherence to topical glaucoma medications and associated factors in Gondar University Hospital Tertiary Eye Care Center, Northwest Ethiopia. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2019;29(2):189-195. doi:10.1177/1120672118772517

25. Newman-Casey PA, Killeen OJ, Renner M, Robin AL, Lee P, Heisler M. Access to and experiences with, e-health technology among glaucoma patients and their relationship with medication adherence. Telemed J E Health. 2018;24(12):1026-1035. doi:10.1089/tmj.2017.0324

26. Olthoff CM, Schouten JS, van de Borne BW, Webers CAB. Noncompliance with ocular hypotensive treatment in patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension an evidence-based review. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(6):953-961. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.12.035

27. Lewis RA, Christie WC, Day DG, et al. Bimatoprost sustained-release implants for glaucoma therapy: 6-month results from a phase I/II clinical trial. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;175:137-147. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2016.11.020

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.