Propolis may help treat ocular disease

The benefits of bee pollen on health have been investigated for years. Dr. Michael Cooper examines how propolis, a natural wax-like resinous substance found in beehives, can help treat ocular disease.

With a delayed spring and allergy season this year, I began to think about how to shape the global warming discussion from an objective standpoint. It is certainly a hot topic in both media and scientific circles. Essentially, our world is changing whether we like it or not.

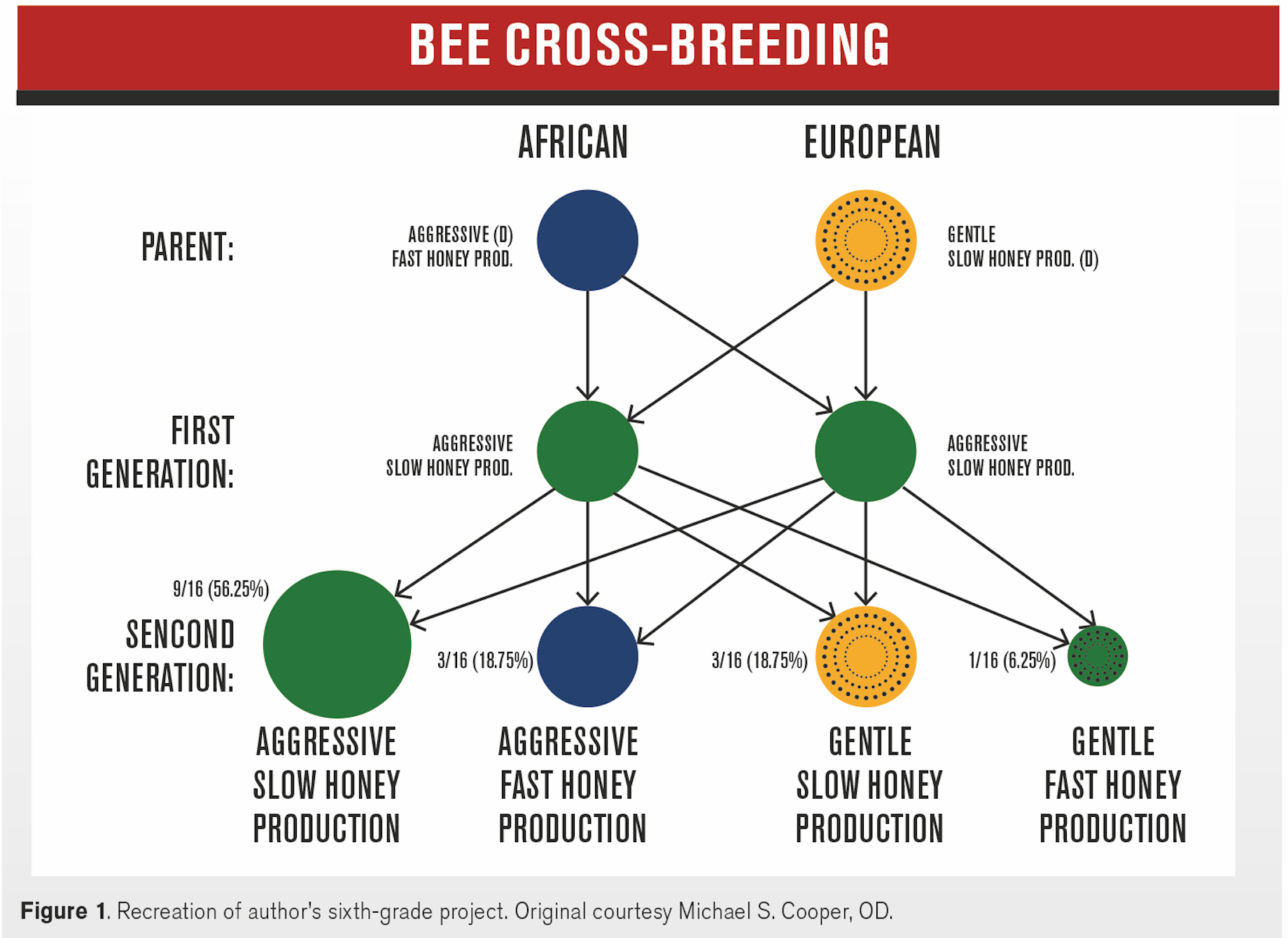

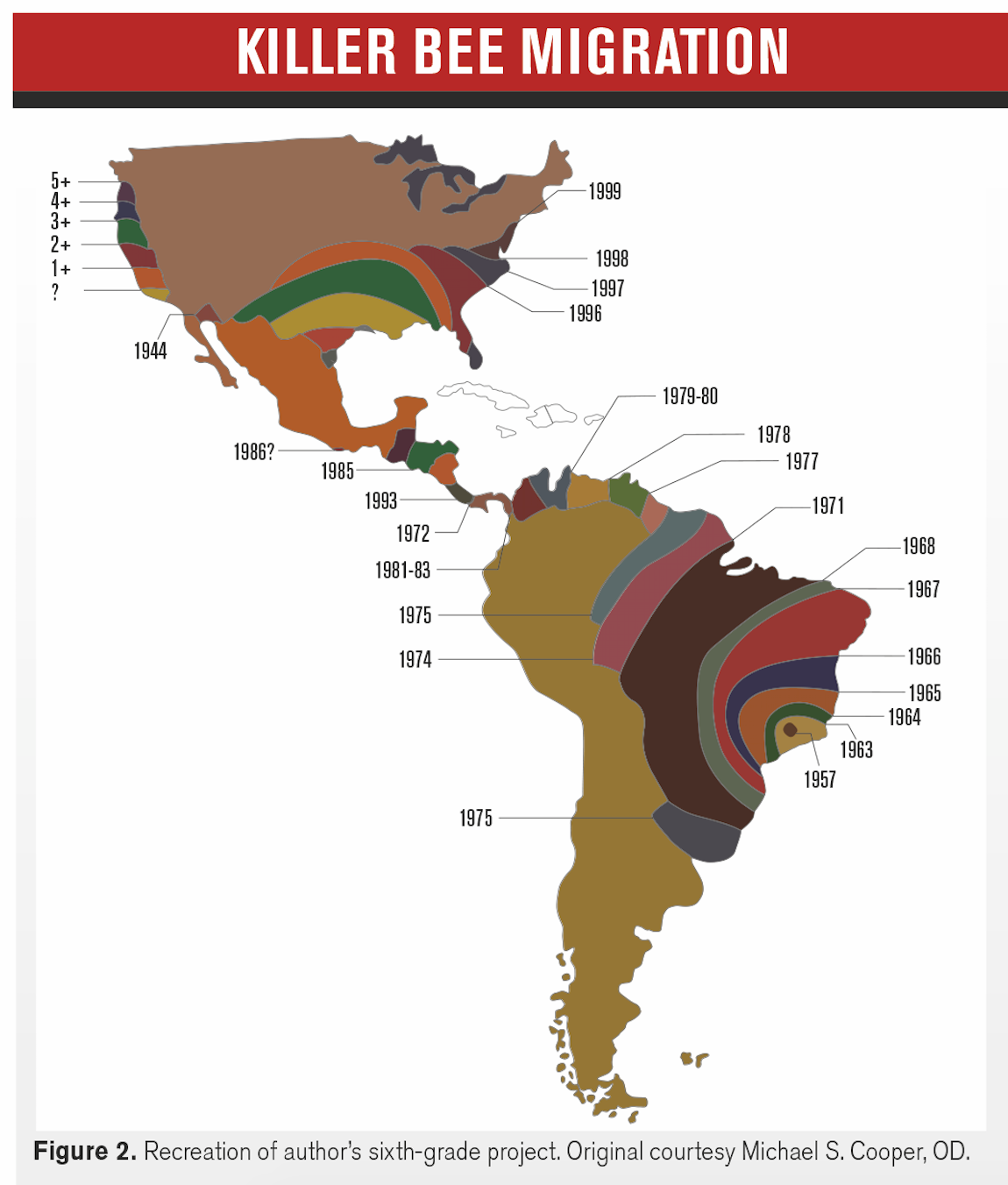

My realization of global warming started when I was in the sixth grade. My teacher Mr. Finnerty tasked the entire class with projects on how humans impact ecological change. As fortuitous as this might sound, the subject matter I tripped upon was killer bees (Figure 1).

Related: Surviving allergy season as a contact lens wearer

Bees together

In the mid- to late 1950s, the Africanized Bees program in Brazil was touted to be the perfect marriage of the gentle Western European bee (Apis mellifera-specifically Italian and Iberian) and African bee (Apis m. scutellata) to increase honey production.1,2

Although these organisms blended the organization, consistency of the former with the rapid, frenetic nature of the latter for honey production, there were two important drawbacks.

The African bee was exceedingly territorially defensive, which dominated the genetic pairing with the European bee. This trait was further enhanced with a significant lack of interest in hive mentality and the penchant to chase a person to up to 400 meters or a quarter mile away, stinging 10 times more.3,4

Parallel propolis

The parallels might not seem apparent, but the dichotomy described can be brought back to inflammation and homeostatic balance. Inflammation plays a key role in maintaining normal systemic function, but if left unchecked the process breaks down.

Bees have a known hierarchy of certain jobs, including the construction of the hive. Propolis is a natural wax-like resinous substance found in beehives used by honeybees as cement and to seal cracks or open spaces in the hive. 5

The best sources of propolis are species of poplar, willow, birch, elm, alder, beech, conifer, and horse-chestnut trees.6 If the colony experiences a lack of propolis content due to disease and/or temperature variations, the hive composition will lack adhesiveness or be brittle-which could lead to structural failure.

It is now generally accepted that propolis is collected by worker honeybees from tree buds or other botanical sources in the north temperate zone. This zone extends from the Tropic of Cancer to the Arctic Circle.6

Foraging for propolis is known only with Western or European honeybees with several notable subspecies or regional varieties, such as the Italian bee (Apis mellifera ligustica), European dark bee (Apis mellifera mellifera), and the Carniolan honey bee (Apis mellifera carnica).7

Tropical honeybees (Apis cerana, Apis florae, and Apis dorsata) and African Apis mellifera make no use of propolis due to their transient nature.8

Propolis composition

In each sample of propolis, more than 80 to 100 chemical compounds are identified.9 A broad analysis revealed about 50 constituent elements in European propolis comprised primarily of resins and vegetable balsams, mainly cinnamic acid and derivatives, coumaric acid, prenylated compounds, artepillin C (50 percent), beeswax (30 percent), essential oils (10 percent), bee pollen (5 percent), and minerals, polysaccharides, proteins, amino acids, amines, amides, and organic debris (5 percent).10

This trend has resulted in propolis being produced in diverse forms for various maladies, including pharmaceutical and cosmetic products. Propolis is sold in many health food stores in pill forms, lozenges, cough syrups, toothpastes, rinses, shampoos, ointments, lotions, and cosmetics.11

The caveat is that these free aromatic acids can also act as sensitizers with 3-methyl-2-butenyl caffeate and phenylethyl caffeate as the major and benzyl salicylate and benzyl cinnamate as less frequent culprits.11-15

Ocular implications

Ophthalmic preparations have shown promise; for example, in treating corneal neovascularization (CNV). One study hypothesized that the antiproliferative properties of propolis from caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) and flavonoids might inhibit the cyclo-oxygenase and lipo-oxygenase pathways leading to corneal neovascularization.15

Researchers compared a 1 percent water extract of propolis (WEP) to dexamethasone 0.1% and saline to determine whether it was effective in controlling CNV in rabbits. By utilizing silver nitrate to cauterize a specific area of the cornea (5 to 5.5 mm), these animals were analyzed after seven days with significantly reduced signs treated with topical WEP 1 percent (41.0±14.1) and dexamethasone 0.1% (39.4±11.0) in almost equal proportions compared with controls.15

Investigators concluded that the anti-inflammatory activity of propolis might be related to its effects on the various mediators of inflammation such as prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and histamine.16,17

Read more from Michael S. Cooper, OD.

References:

1. Winston ML, Taylor OR, Otis GW. Some differences between temperate European and tropical African and South American honeybees. Bee World. 1983;64(1):12-21.

2. Fewell JH, Bertram SM. Evidence for genetic variation in worker task performance by African and European honeybees. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 2002;52(4):318-25.

3. Gore R. Those fiery Brazilian bees. Nat Geo. 1976;149(4):491-501.

4. Michener CD. The Brazilian bee problem. Annu Rev of Entomol. 1975;20:399-416.

5. Philipp PW. Propolis, its use and origin in the hive. Biologishes Zentralblatt. 1928;48:705-714.

6. Ghisalberti EL. Propolis: A review. Bee World. 1979;60(2):59-84.

7. Crane E. Bees and Beekeeping: Science, Practice and World Resources. 1990. Heinemann Newnes, Oxford.

8. Singh Z. Propolis collection and its use. Indian Bee J. 1972;34:11-19.

9. Marcucci MC, Ferreres F, GarcÃa-Viguera C, Bankova VS, De Castro SL, Dantas AP, Valente PH, Paulino N. Phenolic compounds from Brazilian propolis with pharmacological activities. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001 Feb;74(2):105-12.

10. Cirasino L, Pisati A, Fasani F. Contact dermatitis from propolis. Contact Dermatitis. 1987 Feb;16(2):110-1.

11. Walgrave SE, Warshaw EM, Glesne LA. Allergic contact dermatitis from propolis. Dermatitis. 2005 Dec;16(4):209-15.

12. Kim JE, Shin H, Ro YS. A case of allergic contact dermatitis to propolis on the lips and oral mucosa. Korean J Dermatol. 2009 Feb;47(2):199-202. Korean.

13. Valsecchi R, Cainelli T. Dermatitis from propolis. Contact Dermatitis. 1984 Nov;11(5):317.

14. Giusti F, Miglietta R, Pepe P, Seidenari S. Sensitization to propolis in 1255 children undergoing patch testing. Contact Dermatitis. 2004 Nov-Dec;51(5-6):255-8.

15. HepÅen IF, Er H, Cekiç O. Topically applied water extract of propolis to suppress corneal neovascularization in rabbits. Ophthalmic Res. 1999;31(6):426-31.

16. Mirzoeva OK, Calder PC. The effect of propolis and its components on eicosanoid production during the inflammatory response. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1996 Dec;55(6):441-9.

17. Khayyal MT, el-Ghazaly MA, el-Khatib AS. Mechanism involved in the antiinflammatory effect of propolis extract. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1993;19(5):197-203.

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.