Spiking IOP not what I thought

Michael Brown, OD, has practiced medical optometry in a comanagement center and with the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs Outpatient Clinic in Huntsville, AL, for over 25 years.

Plink, plink, plink…plink!

The noise should clue me in on what is happening, but we optometrists are visual processors primarily, not auditory ones. We are supposed to listen to what our patients tell us and the noises their eyes make, but now the din of my panicked thoughts drowns out the sound.

My God, I think, he’s sitting there so calm like nothing’s wrong. How does he stand the pain? Oh no, please, not again! Everything is so white; where’s the fluorescein?

See more: 5 lessons I learned from visiting another dry eye practice

My heart races at the sight of tonometry mires miles apart with no chance of overlapping soon, no matter how much I turn the measuring drum.

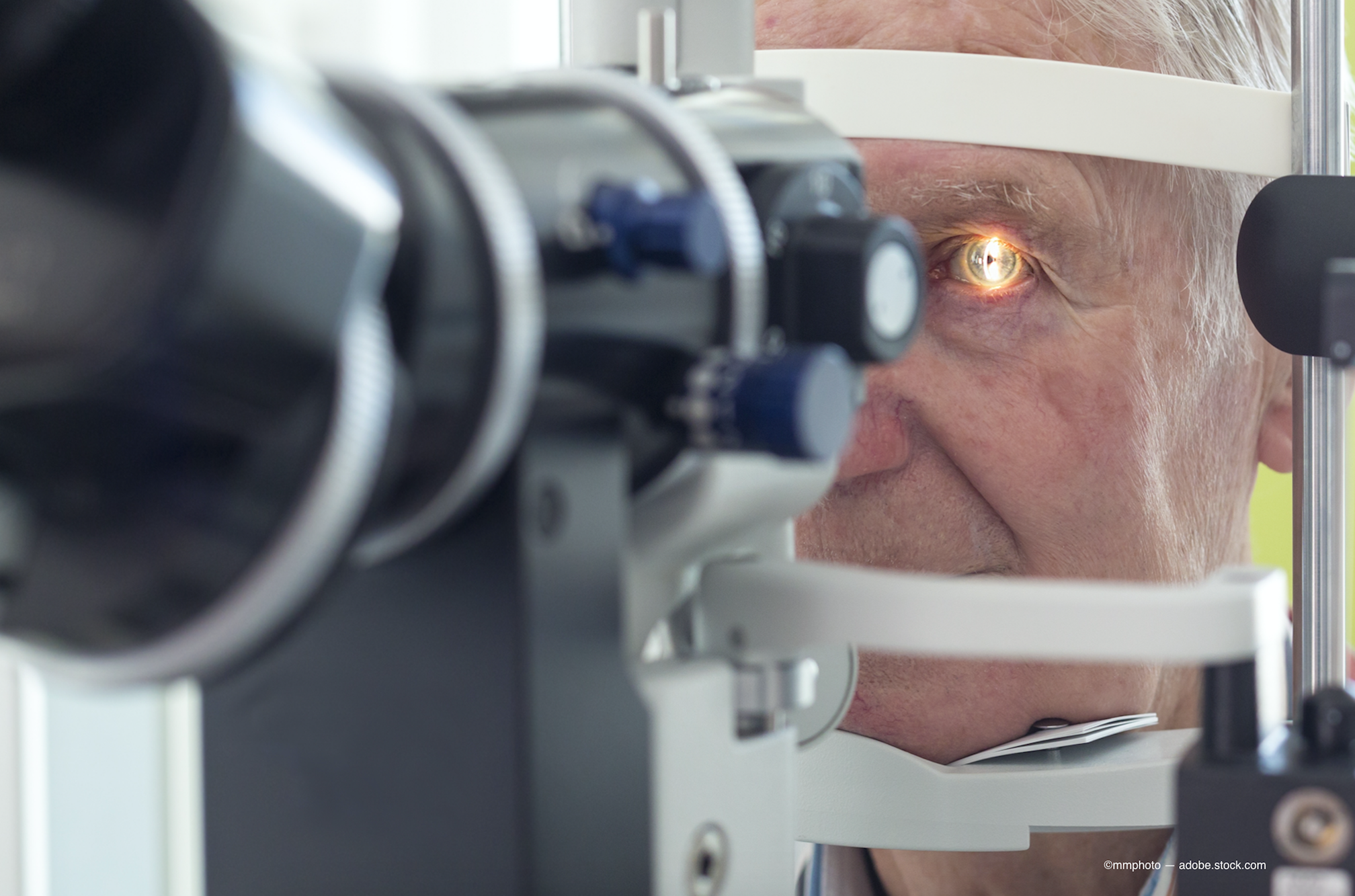

I am ready to launch an all-out frontal assault on the spiking intraocular pressure (IOP) in his right eye when Mr. H. reaches around the slit lamp and touches my arm.

“Dr. Brown, I need to tell you something. It’s an…”

Before he can complete the line, I remember.

See more: Why practice owners should create a simple business budget

History of Mr. H

Seven years before, Mr. H had been a patient with mild open-angle glaucoma. His condition was easily managed, and he was an affable man whose company I enjoyed.

I cringe when I see certain patients’ names on the schedule, but not Mr. H’s. We had clicked, and our conversation topics included current events, books we had read, and the origin and meaning of surnames.

He had disappeared for a while, as Veterans Affairs (VA) patients sometimes do. They usually find their way back, and when they do, we always pick up where we left off. I stress the importance of regular follow-up care and medication use, and they depart with a date and time for their next appointment.

Related: How ODs should handle non-compliance with contact lens replacement

In Mr. H’s case, he had continued with his drops but had become sidetracked through a series of unfortunate miscues and miscommunications. Thinking, incorrectly, that he would no longer be eligible for care in our clinic, he ended up seeing a community-based doctor.

That doctor apparently didn’t recognize that Mr. H’s swelling nuclear sclerotic cataracts had accelerated into overdrive and were pushing on his irises, causing them to bow forward and narrow his anterior chambers.

The night after he was dilated and examined, Mr. H suffered an angle closure attack in his right eye. In severe pain, he went to the ER where the staff physician prescribed opioid tablets, gentamicin drops, and ordered a next-day consult with a different community-based doctor.

Related: Laser vision correction: Look backward to move forward

That doctor, rather than managing his intraocular pressure (IOP) of 70 mm Hg aggressively and emergently, instead, for reasons beyond my comprehension, only prescribed more drops (no orals) and didn’t perform a laser peripheral iridotomy (LPI) or refer him to a glaucoma specialist who would.

Three weeks passed, and the patient’s daughter eventually insisted her father see a different doctor. A glaucoma specialist finally performed the cataract and tube shunt surgery he needed, but the damage was already done.

Related: Prosthesis system may help blind patients 'see' again

Mr. H returns

I learned all of this when Mr. H came back and brought his records. He wanted me to help him understand what had happened and why he was going blind in his right eye.

“I regret I didn’t come back to see you the morning after it happened,” Mr. H said. “I know you would have done the right thing.”

I wished he had, too. But since he was back, I was determined to make sure every base was covered.

His vision in his right eye was light perception only (LPO) and his IOP was still in the high 20s, tube shunt notwithstanding. Thankfully, his left eye’s acuity was 20/20 and IOP 15 mm Hg-but then I saw it.

His left angle was extremely shallow by Van Herick. It didn’t take gonioscopy to know there was trouble brewing in that eye also, but I did it anyway and saw no visible structures.

Related: Diagnosing and managing patients with narrow angles

I scanned his notes again. His IOP and visual acuity in his left eye had been measured and recorded at each visit, but there was no mention of its angle morphology in the objective findings, nor in any assessment and plan.

Even the best doctors can become distracted in the heat of battle and prone to medical errors. I asked Mr. H if his current doctor had mentioned removing the cataract in his left eye and he replied, “No.”

I phoned his glaucoma specialist immediately. “Mr. H’s left angle is in danger of closing, too. He needs cataract surgery ASAP!” I said.

Related: Managing dry eye key to patient satisfaction after cataract, refractive surgeries

There was a long pause as he considered my words. Then he replied, “Send him over right now.”

The next day, the glaucoma specialist removed the cataract in Mr. H’s left eye and cured the phacomorphic component of his disease, at least.

One eye lost and one eye saved, but I took little solace in the latter. Instead, I went home and drank too much in an ill-advised attempt to numb my pain.

I remember two things about that night: I was a weepy drunk, and my wife was a saint. She endured my second-guessing and mournful wails as we sat shiva over Mr. H’s right eye well into the night.

Related: Cataract surgery problem solving: Is technology the answer?

Joyful noise

Back to today, Mr. H and I are once again facing each other and the past events that have bound us together. I watch over him now with the vigilance of a sheepdog guarding the smallest of the flock.

It is such passion and purpose that temporarily blinds me and causes me to forget, until he touches my arm, that years before Mr. H elected to have his right eye enucleated to ease his pain.

More by Dr. Brown: Too many cooks in the kitchen spoil the broth

I lean back, slap my hand to my forehead, and complete the line Mr. H was set to deliver: “It’s an artificial eye!”

My 30-plus year streak of not attempting to measure the IOP of a prosthesis is over.

I am more amused and relieved than I am embarrassed. I grab his arm in return, and we double over in laughter.

The plink of plastic on plastic is replaced with the joyful noise of two pilgrims traveling a long, hard road toward redemption.

More by Dr. Brown: ODs must swim in ‘deep end of the pool’ and avoid over referring

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.