Substance P: Dry eye and allergy’s mixed signal or missing link?

Inflammation may lead to heightened peripheral sensitization and stimulation through a developing concept in which neuroimmune cross-talk causes the confounding interplay of both signs and symptoms in dry eye and allergic disease.

In 2009, a seismic shift in the world of paleoanthropology occurred when a new entry into the fossil record occurred with the advent of “Ardi” (Ardipithecus ramidus).1

Now, you may remember “Lucy” (Australopithecus afarensis) from your biology class back in the day as the oldest known human relative approximately 3.2 million years ago that was considered the missing link. By all accounts, Lucy and her brethren walked upright and had increased brain capacity in the woodland savannas of Africa.

Everyone thought this was case closed in 1974-until Ardi came into the picture about 4.4 million years ago.1

Ardi is a hodgepodge of sorts in that she had mixed bone structure revealing she was a quadruped in the trees and lived a biped lifestyle on the ground. Although her brain was smaller than Lucy’s, she had the potential vocal ability to socialize with others due to craniofacial modification.2

Previously from Dr. Cooper: Epicutaneous immunotherapy may transform allergy treatment

It’s not a tangent

You are likely asking yourself, how does the early human fossil record remotely connect to dry eye and allergic disease? The simple answer is everything.

There is growing evidence in the literature over the past 20 years with synthesized compounds such as cyclosporine (Restasis, Allergan) and lifitegrast (Xiidra, Shire) that there might be more than the straightforward inflammatory response story we all accept as stalwart vernacular.

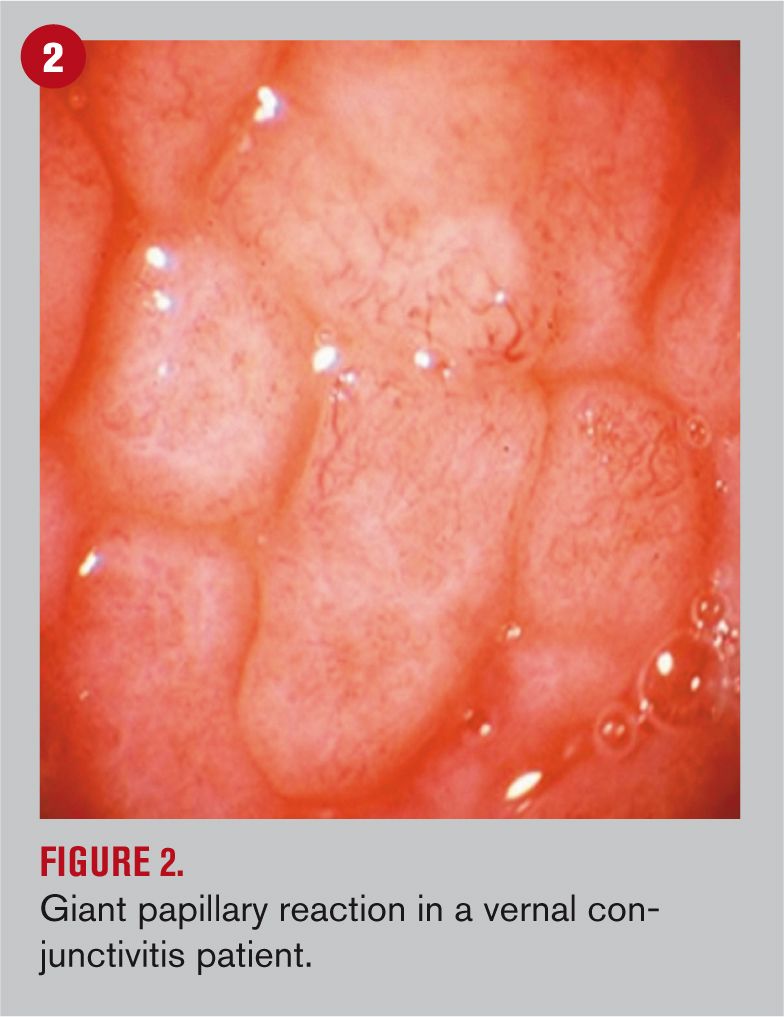

Müller et al described the rich plexus of corneal nerves that provide innervation which is the richest in the human body. Furthermore, this leads into a concept where potential hierarchal complex neurological and inflammatory microsystems feed back and forth.3

Optometry Times Editorial Advisory Board Member Milton Hom, OD, FAAO, in a passing conversation categorized inflammation the best when stating that we need it for healing purposes to essentially draw in the immune system but not when the reaction is allowed to sustain itself for longer periods of time.

With this in mind, neurogenic inflammation comes to the forefront as the result from the release of substances from primary sensory nerve terminals.4 In fact, these neuromediators act on target cells and exert their biological activity on both mast cells and immune cells to prolong inflammation.

Mixed or missing?

Substance P is an 11-amino acid peptide generally associated with neurogenic pain ranging from intense to chronic present in physiologically relevant tear concentrations.5

Lai et al illustrated that this particular compound emanates from eosinophils, monocytes, lymphocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells with an inflammatory trigger.6

Subsequently, the induction of pain facilitates vasodilation that can increase vascular permeability of the surrounding tissue which stimulates mast cells and B to T lymphocytes as well as acts as a chemotactant for eosinophils.

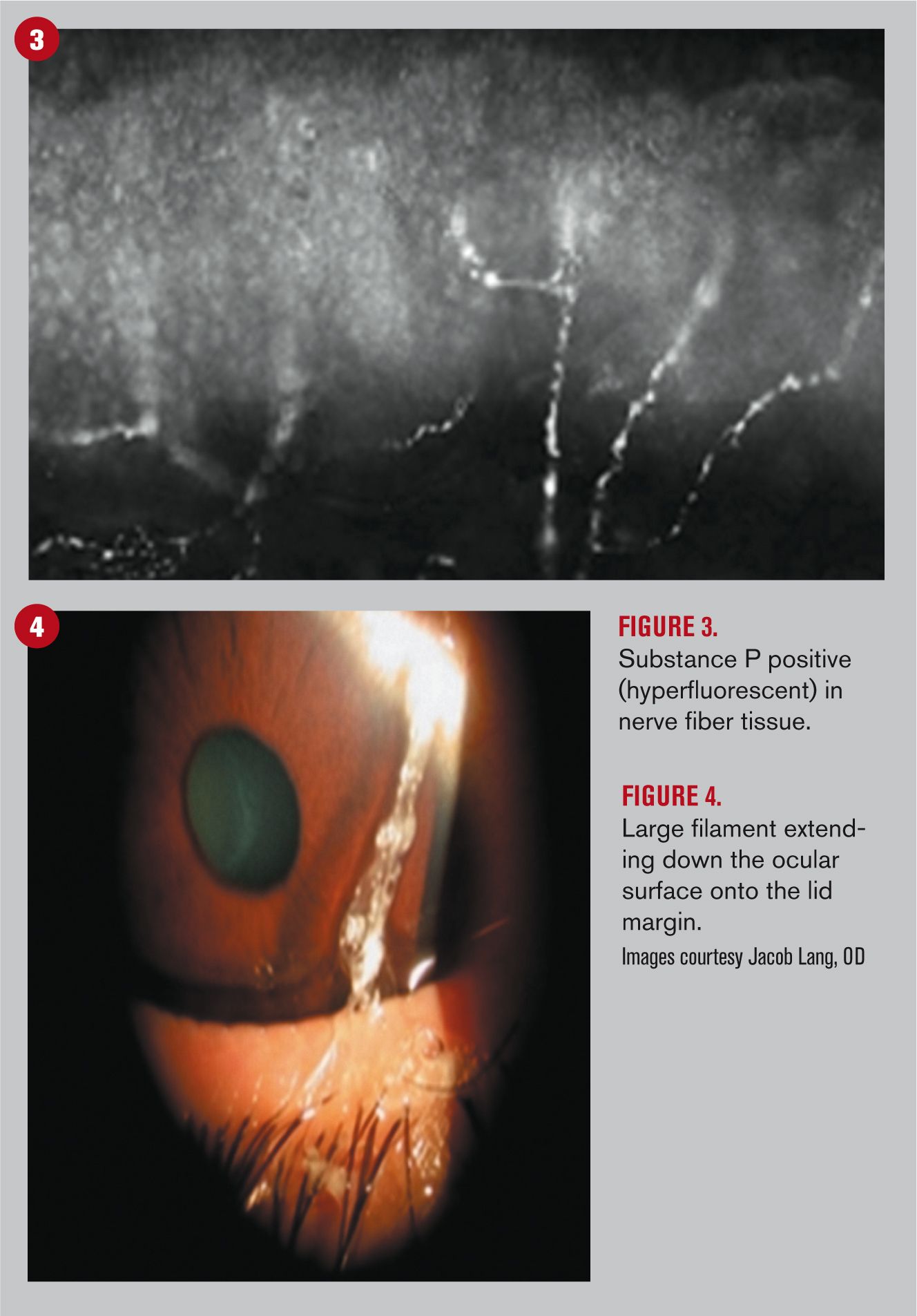

With regard to dry eye disease, the chronic inflammatory response impacts nociceptors in the damaged dendritic space to initiate a sensation of pain. In turn, these receptors are stimulated after impairment due to a release of tachykinins such as Substance P and RNA-derived Calcitonine gene-related peptide (CGRP) to which they are sensitive.7

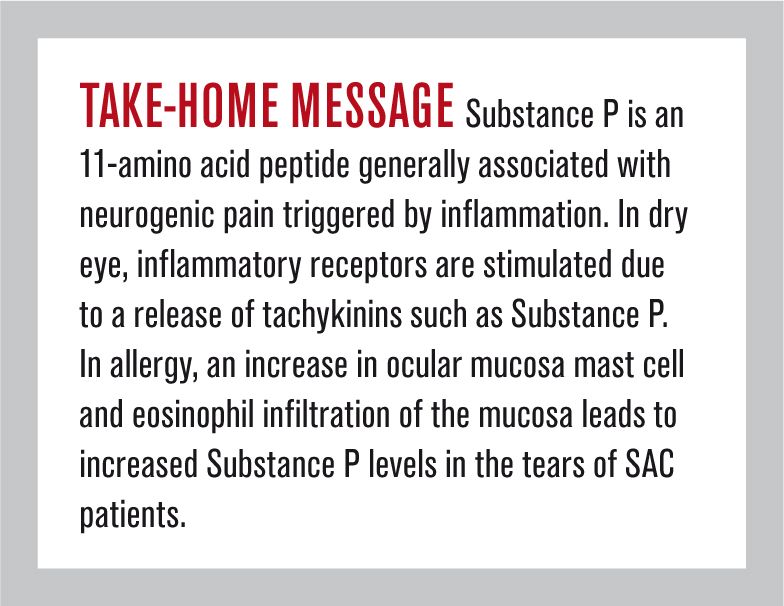

For the cornea, these receptors are primarily chemical sensors, but they are interrelated to mechanical and thermal stimuli in reference to recalcitrant superficial keratopathy, increased pH levels, and elevated tear osmolarity.8,9

Evidence of such involvement of neuromediation affecting the ocular surface has been growing in the last two decades, suggesting that neuropeptides released from sensory and autonomic sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves may influence the pathogenesis and progression of dry eye and other autoimmune diseases.10

Consequently, the increased secretion of these compounds may lead to a widespread chronic inflammatory response in which the ocular surface reaches a breaking point, causing meibomian glandular structure to undergo some level of hyperkeratinization, dysregulation of tear production by the lacrimal gland, and mucin decompensation due to deficient conjunctival goblet cells.11-13

Related: How palynology and aldehydes affect allergy treatment

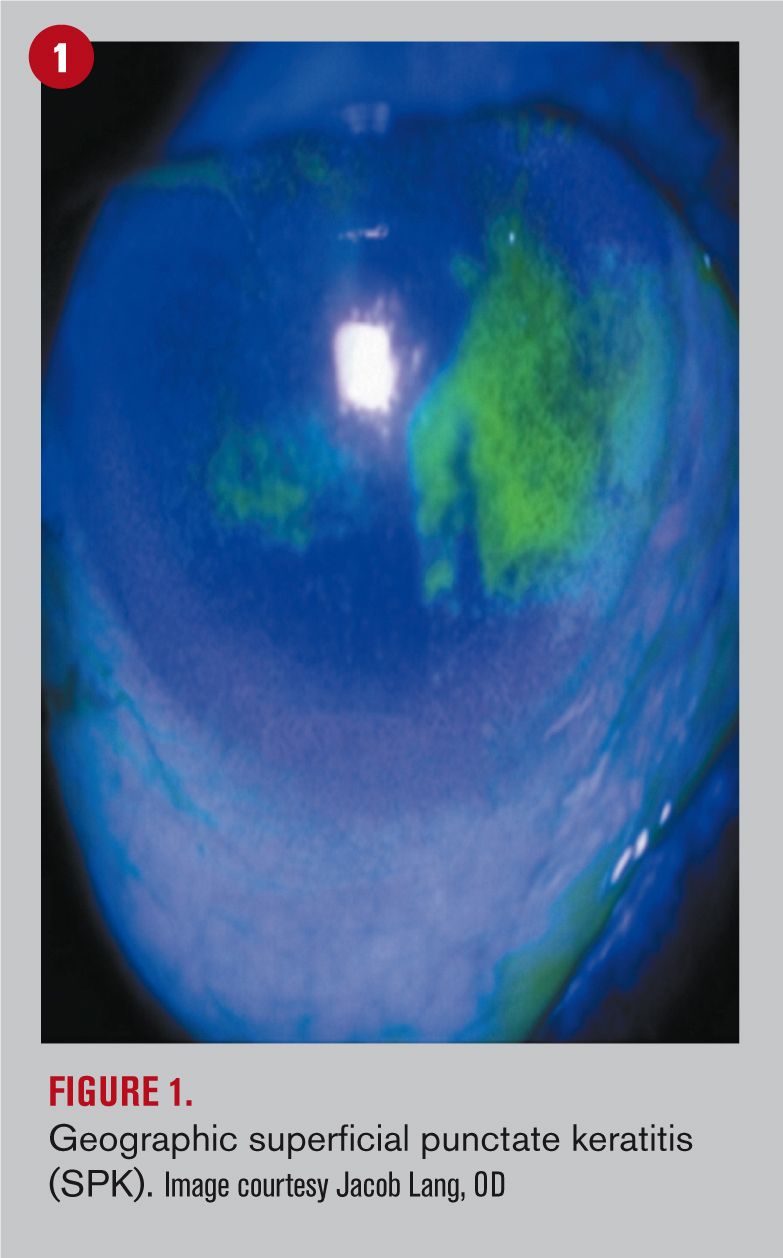

Switching gears to allergic conjunctivitis, the hallmark inflammatory response is a delayed Type IV hypersensitivity. Diving deeper into the ocular surface mucosa, both mucin-secreting goblet cells and a fine network of sensory nerve terminals are found in allergic diseases such as seasonal or perennial allergic conjunctivitis (SAC and PAC), atopic (AKC), and vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC).14

By virtue of an increase in mast cell and eosinophil infiltration of the mucosa, it has been reported that Substance P levels are increased in the tears of patients with SAC compared with healthy individuals, suggesting that the compound may contribute to the pathogenesis and severity of allergic conjunctivitis.15

With specific focus to the itching sensation, it is postulated that the peripheral nervous system could play a major role in its pathophysiology. With the symptom being triggered and maintained by stimulation of the nerve endings, inflammatory neuropeptides such as Substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptid (CGRP) foment the inflammatory cascade.16 A broadened molecular investigation of the neuropeptide effect is clearly required to gain a greater understanding of their involvement as to the presence, release, and specific roles played in ocular allergic reactions.

Conclusion

Succinctly, inflammation may lead to heightened peripheral sensitization and stimulation through a developing concept in which neuroimmune cross-talk causes the confounding interplay of both signs and symptoms in dry eye and allergic disease.

Furthermore, this cascading response may propagate a neurogenic amplification of the inflammatory responses in a vicious loop that could have both protective and detrimental effects depending on the levels of a single neuropeptide entity.

Therefore, it can be hypothesized that by peering into the mechanisms behind neurogenic inflammation this will hopefully soon dispel the ocular version of Lucy vs. Ardi in order to yield better treatment and stabilization of the disease activity through appropriate modulation of specific neuropeptides.

References

1. Shreeve J. Oldest Skeleton of Human Ancestor Found. Nat Geo. 2009 Oct 01. Available at: http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2009/10/091001-oldest-human-skeleton-ardi-missing-link-chimps-ardipithecus-ramidus.html. Accessed 7/30/17.

2. Clark, G, Henneberg M. Ardipithecus ramidus and the evolution of language and singing: An early origin for hominin vocal capability. Homo. 2017 Mar;68(2):101-121.

3. Müller LJ, Marfurt CF, Kruse F, Tervo TM. Corneal nerves: structure, contents and function. Exp Eye Res. 2003 May;76(5):521-42.

4. Richardson JD, Vasko MR. Cellular Mechanisms of Neurogenic Inflammation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002 Sep;302(3):839-45.

5. Bonini S, Lambiase A, Bonini S, Levi-Schaffer F, Aloe L. Nerve growth factor: An important molecule in allergic inflammation and tissue remodelling. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1999 Feb-Apr;118(2-4):159-62.

6. Lai JP, Douglas SD, Wang YJ, Ho WZ. Real-Time Reverse Transcription-PCR Quantitation of Substance P Receptor (NK-1R) mRNA. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005 Apr;12(4):537-41.

7. DeVane CL. Substance P: A new era, a new role. Pharmacotherapy. 2001 Sep;21(9):1061-9.

8. Farris RL, Stuchell RN, Mandel ID. Tear osmolarity variation in the dry eye. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1986;84:250-68.

9. Tomlinson A, Khanal S, Ramaesh K, Diaper C, McFadyen A. Tear film osmolarity: determination of a referent for dry eye diagnosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006 Oct;47(10):4309-15.

10. Beuerman RW, Stern ME. Neurogenic inflammation: a first line of defense for the ocular surface. Ocul Surf 2005; 3(4 Suppl):S203–S206.

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.

.png&w=3840&q=75)