Look for small signs to prevent contact lens complications

Perhaps many complications with contact lenses wouldn’t become complications if patients were to pay closer attention. But since they’re so highly motivated to wear them, they often miss the signs.

The advances in designs and materials ODs and patients have seen from the contact lens (CL) industry have created a heightened awareness and buzz about contact lenses.

Patients perceive them as being healthier than in the past. They may even assume that now they can push the limits of CL wear even further, without the fear of consequences they had previously. ODs know this isn’t true, and risks are still very real.

Perhaps many complications wouldn’t become complications if patients were to pay closer attention. But because they are so highly motivated to wear their lenses, they tend to miss the signs.

Patients may tolerate and even ignore mild redness, discomfort, and blurriness. Some of this behavior might be subconscious or blatant, and some of it may not be their fault.

Related: 5 methods to drive contact compliance

CL wearers tend to have less corneal sensitivity than non-wearers, so their threshold for discomfort is often much higher than a non-CL wearer. Redness without pain is then overlooked as unimportant. This causes a delay in diagnosis and treatment and reduces their chance of having a favorable outcome.

Additionally, patients don’t often associate indiscretions in their lens care and wear regime with potential complications. They don’t realize the consequences until it’s too late.

Here are details surrounding a select number of CL complications.

CLARE

Contact lens-induced acute red eye (CLARE) is inflammatory. The problem with an inflammatory condition is that while ODs know it is a reaction to something, they don’t always know the underlying cause.

The patient often presents with circumlimbal injection, several small <2 mm nonstaining infiltrates, mild photophobia, and tearing, but no anterior chamber reaction.

Typical causes include: hypoxia, CL overwear (noncompliance), toxic effects from trapped tear debris, mechanical irritation from a poor-fitting lens, dehydration of the lens with extended wear, solution hypersensitivity or toxicity, or a reaction to bacterial toxins (blepharitis).

But because we often don’t know the cause, the initial course of action is to treat it, change the underlying wearing conditions, and monitor for recurrence.

In some cases, it is important to suspend lens wear immediately and initiate supportive treatments to include lubrication and mild steroids. ODs should ask patients detailed questions about past episodes and remedies they may have tried. This is often the patient who routinely dips into that leftover bottle of Tobradex (tobramycin/ dexamethasone, Alcon) from years ago.

Related: 5 tips to enhance the patient contact lens experience

After resolution, the lens material, fit, and solution need to be evaluated for their potential contribution to the inflammatory event. Ideally, the patient is converted to daily disposables.

Patient education is key for long-term resolution. Patients need to understand that the redness is a manifestation of unhealthy wearing conditions. It's not about fixing the red eye-it’s about changing the underlying conditions that created the red eye.

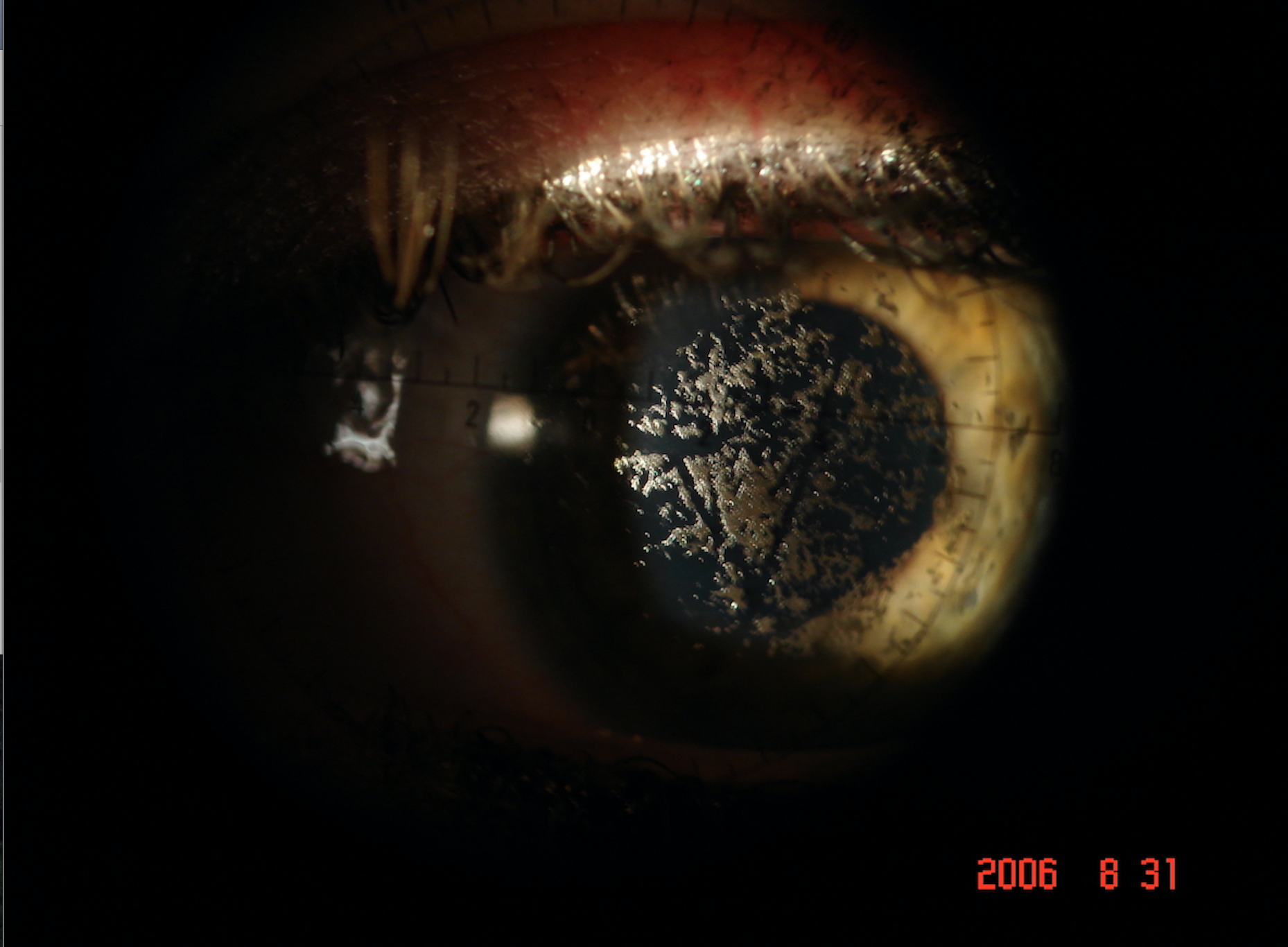

Figure 2. Corneal infiltrate/impending ulceration in a noncompliant soft contact lens patient. Image courtesy Michael W. Ohlson, OD, FAAO

SEAL

Superior epithelial arcuate lesion (SEAL) typically presents as an arcuate erosion that occurs in the superior cornea under the upper lid. The lesion can consist of coalescent or diffuse staining, with or without infiltrates. It can be just inside the limbus or further down, corresponding to the lid margin.

A patient may complain of a foreign-body sensation or be completely asymptomatic. The lesion might be due to mechanical offense by the contact lens, making it essential that the patient discontinues CL wear immediately. The condition could also be heavily influenced by the properties of the lens.

Even if a patient is asymptomatic, the problem should be identified and fixed because any epithelial break is an opportunity for bacteria to get a foothold into the cornea.

SEAL is influenced by lens material, lens modulus, lens design (back surface change or optic zone junction), and lid force that can trap tear debris and create a dry area.

Lubrication is typically helpful to soothe patient symptoms and speed epithelial healing. If the abrasion is particularly large or deep, an antibiotic ointment may be incorporated as a prophylaxis. The lesion typically resolves within one week without scarring.

Patients must be refitted into a different lens, preferably of a different design and softer material. An ideal lens for patients experiencing SEALs may be a hydrogel daily disposable with its typically low modulus and thin design.

Because this condition is not induced by a lack of oxygen, it is not essential that a patient wears silicone hydrogel silicone hydrogel (sihy)lens. In fact, it may be more important that patients wear a particularly soft and thin lens that will induce less mechanical irritation.

These patients should be followed closely to monitor for recurrence in the new lens.

Educate these patients to look under the upper lid for redness and be aware of any slight irritation.

Infiltrates

Infiltrates can be infectious or non-infectious. Non-infectious infiltrates can vary in presentation and appear multiple or singular.

When multiple, infiltrates are typically spread across the cornea. When singular, they tend to be localized in the periphery near the limbus. They may not stain depending on the severity.

When there are multiple infiltrates, a diffuse injection is likely. However, when there is a single infiltrate, the injection is likely localized to that region. The patient may be asymptomatic or may have significant photophobia.

Read Optometry Times' contact lens department

Infiltrates are an immune driven response initiated by a corneal insult that initiates an inflammatory cascade. Inflammatory cells invade the cornea, creating a dense, focal accumulation.

If the infiltration in dense enough, it will cause a secondary epithelial defect above the infiltrate. This is more common when it is a singular event. Because the treatment protocol is significantly different, it is essential that the overlying defect is differentiated as infectious or non-infectious in nature.

Extended wear of any lens increases the risk of noninfectious infiltrates.1 A higher incidence of infiltrates was also seen in those wearing sihy lenses versus hydrogels on a daily wear basis, and in younger patients.

Daily disposables reduce the risk of infiltrates. For patients sleeping in their lenses, sihy lenses caused fewer infiltrates and less severe events when compared to sleeping in hydrogel lenses.2

Infectious etiologies

Infectious infiltrates can have various etiologies: bacterial, fungal, protozoan (Acanthamoeba), and viral (herpetic). Because these require immediate and intense medical treatment, it is essential for ODs to ensure their staffs knows what combination of signs and symptoms indicate the need for immediate attention.

Infectious ulcers are a disruption of the epithelial surface with a secondary necrosis of the surrounding tissue. Unlike noninfectious infiltrates, these start on the surface and invade deeper into the cornea.

There is usually an insult to the outer epithelium that allows the organism to get a foothold into the cornea. However, patients with chronic conjunctivitis or keratitis are also at higher risk.

Read more from Crystal M. Brimer, OD, FAAO

Infectious ulcers cause intense pain and an extremely red eye. The patient will likely have photophobia, discharge, reduced vision, focal epithelial defect with surrounding corneal haze, and an anterior chamber reaction.

Remind staff that if a CL patient calls in reporting a white dot on her eye, or if the patient has significant pain and a questionable reduction in vision, the patient should see a specialist immediately.

Treatment

Ulcers are treated with anti-infective drops and ointments specific to the causative organism. Cycloplegic drops dilate the eye and decrease the pain from iris movement and prevent potential lens adhesion, which can occur with an inflamed eye.

In the case of bacterial ulcers, steroids are sometimes used once the antibiotic is showing successful regression of the infection (typically after 48 hours of antibiotic use). The purpose of the steroid is to potentially reduce residual scarring.

Ulcers will scar and can potentially reduce the patient’s vision permanently. If the ulcer is not treated successfully in a timely manner, it can cause a corneal perforation, iritis, or even endophthalmitis.

With fungal ulcers, the patient has typically had exposure to vegetation, or the individual may work in a nail salon. Acanthamoeba ulcers usually involve a contaminated water source (or a heating, ventilation and air conditioning source), and almost always CL usage.

What can ODs do to better influence the CL patient’s mindset? Perhaps patients would identify symptoms and be quicker to report them if ODs were to routinely ask purposeful questions before there is an actual problem.

ODs should encourage staff to ask patients at routine visits, in small talk, picking up their lenses, whenever there is an opportunity.

Ultimately, looking for complications will allow ODs to identify problems sooner, causing a speedier recovery and positive overall outcome for the patient and the patient’s vision.

References:

1. Chalmers, RL, Keay L, McNally J, Kern. Multicenter case-control study of the role of lens materials and care products on the development of corneal infiltrates. Optom Vis Sci. 2012 Mar;89(3):316-25.

2. Steele KR, Szczotka-Flynn L. Epidemiology of contact lens-induced infiltrates: an updated review. Clin Exp Optom. 2017 Sep;100(5):473-481.

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.