Toxoplasmosis shows varied diagnosis

Controversy surrounding treatment guidelines plays role in patient case

A 39-year-old male attended the clinic seeking a second opinion for a right-eye problem for which he had been treated elsewhere. The

complaint that brought him initially was blurry vision centrally in the right eye. He reported being treated with oral clindamycin (150 mg, three times a day [tid]).

This treatment had been initiated along with an oral steroid approximately six weeks prior, but he had self-discontinued the steroid after three weeks because he claimed that he disliked the side effects.

He denied taking any prescription medications as well as systemic problems. On clinical examination, best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/200 (OD) and 20/20(OS).

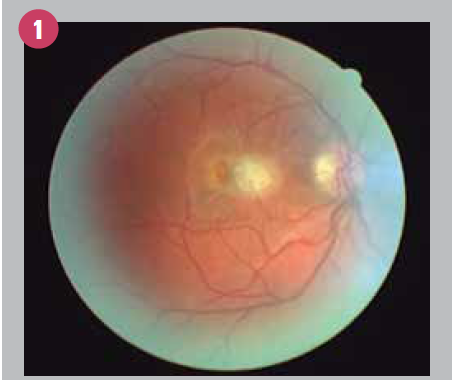

Remarkably, slit-lamp examination showed the absence of an anterior-chamber reaction in either eye, along with mild vitritis involving the right eye only. The fundus appearance (OD) is shown in Figure 1.

Previously by Dr. Semes: Vision loss diagnosis presents potential complications Diagnosis

A working diagnosis of ocular toxoplasmosis was made. Because the clindamycin appeared to be ineffective and the patient denied sulfa allergy, Bactrim DS (trimethoprim/sulfmethoxazole; Roche; 160/800 mg) was prescribed empirically, twice a day (bid), dosing orally. The patient was asked to return in two weeks.

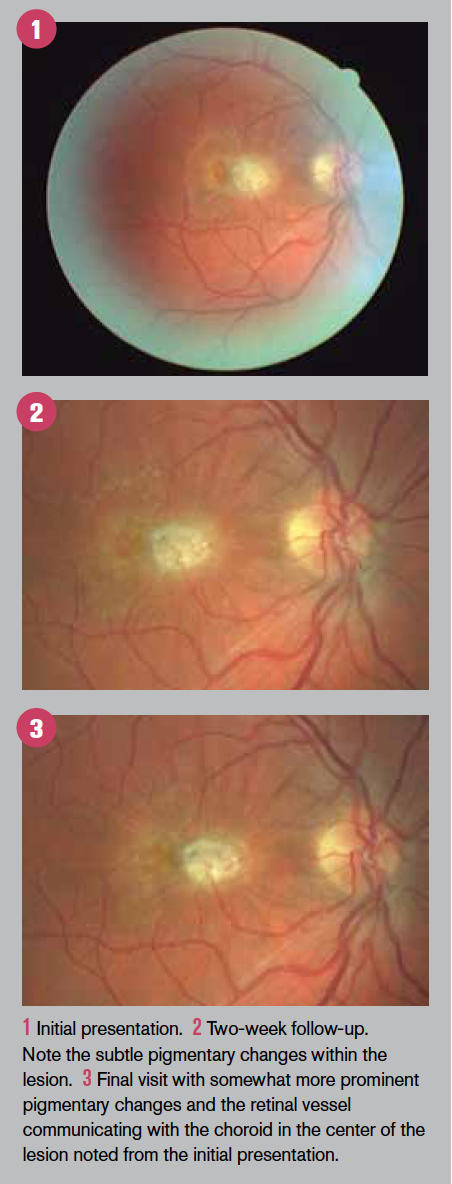

The two-week fundus appearance is shown in Figure 2.

While there appears to be little improvement, the emergence of subtle pigmentary changes can be seen with careful comparison with baseline. The patient was monitored biweekly for the next month.

Following this course of the trimethoprim/sulfmethoxazole combination, the fundus appearance is shown in Figure 3.

Of note is that the central lesion, ascribed to ocular toxoplasmosis, showed an increased pigmentation-indicating further retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) remodeling secondary to the inflammatory process as well as communication of a retinal blood vessel with the choroid as another component of remodeling.

Related: How inflammation may play a role in retinal diseaseTreatment

There has been considerable controversy over the decades concerning the treatment of ocular toxoplasmosis.

What has emerged is a general guideline for recommending treatment, broadly if the infectious nidus involves the posterior pole; that is, if the macular is involved or the optic nerve is threatened.1

While a significant proportion of literature regarding treatment is from outside the U.S., current consensus recommendations for treatment underscore this template by suggesting trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole in combination orally alone in the absence of vitritis and the addition of an oral steroid (prednisone, 40 to 80 mg/day) in the presence of vitritis with biweekly follow-up.2

The clinical presentation of ocular toxoplasmosis is varied. This is likely due to the latency after the initial infection and inflammatory process begins, and if the patient becomes symptomatic or presents for ophthalmic evaluation.3

This spectrum extends from the central lesion presenting initially as a primary retinitis with extension posteriorly (choroiditis) and anteriorly (vitritis). A variety of features consistent with a primary retinitis have also been reported from optical coherence tomography evaluations.4-6

While the diagnosis is typically made from clinical findings, laboratory investigations for systemic involvement can be undertaken.

Related: Case: New protocol for macular hole treatment Analysis

A number of vectors have been identified for the transmission of this obligate intracellular parasite (T. gondii). Those at risk include meatpacking workers, those consuming raw mollusks (oysters, clams, mussels) or locally cured meat, those who may be immunocompromised, or owning three-plus kittens.7

This list is derived from the national toxoplasmosis clearinghouse laboratory at Stanford University. Its purpose it to alert clinicians of potential risks for susceptible patients.

Recurrences of ocular toxoplasmosis are possible. While this risk appears to decrease with age, increasing age makes continued surveillance for recurring vision-threatening recurrences a necessity.8Related: How to diagnose a swollen optic nerve

Finally, the consideration of prophylaxis against future infection must be addressed. One template has suggested that a discussion of a one-year antibiotic regimen should be proposed to any patient with an active lesion.

With frequent recurrences (<2 year), a one- to two-year antibiotic prophylaxis course should be recommended.9 Acknowledgement: The patient was also attended by K. Prezgay, OD.Read retina content here

References:

1. Stanford MR, Gilbert RE. Treating ocular toxoplasmosis: current evidence. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009 Mar;104(2): 312-5.

2. Lima GS, Saraiva PG, Saraiva FP. Current therapy of acquired ocular toxoplasmosis: a review. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2015 Nov;31(9):511-7.

3. Commodaro AG, Belfort RN, Rizzo LV, Muccioli C, Silveira C, Burnier MN Jr, Belfort R Jr. Ocular toxoplasmosis: an update and review of the literature. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009 Mar;104(2):345-50.

4. Monnet D, Averous K, Delair E, Brézin AP. Optical coherence tomography in ocular toxoplasmosis. Int J Med Sci. 2009;6(3):137-8.

5. Chen KC, Jung JJ, Engelbert M. Single acquisition of the vitreous, retina, and choroid with swept-source optical coherence tomography in acute toxoplasmosis. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2016 Summer;10(3):217-20.

6. Vezzola D, Allegrini D, Borgia A, fl. Swept-source optical coherence tomography and optical coherence tomography angiography in acquired toxoplasmic chorioretinitis: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2018 Dec 4;12(1):358.

7. Jones JL, Dargelas V, Robets J, Press C, Remington JS. Montoya JG. Risk factors for Toxoplasma gondii infection in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2009 Sep 15;49(6):878-84.

8. Holland GN, Crespi CM, ten-Dam Loon N, Charonis AC, Yu F, Bosch-Driessen LH, Rothova A. Analysis of recurrence patterns associated with toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008 Jun;145(6):1007-1013.

9. Reich M, Mackensen F. Ocular toxoplasmosis: background and evidence for antibiotic prophylaxis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2015 Nov;26(6):498-505.

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.