- February digital edition 2024

- Volume 16

- Issue 02

A new era of assistive technology for patients with low vision

OrCam devices incorporate cutting-edge AI advancements that empower patients to live more independent lives.

As an occupational therapist working in low vision rehabilitation, I collaborate with a multidisciplinary team to provide the highest level of service possible to patients with visual impairments. Individuals of all ages can experience vision loss due to a variety of conditions—from eye disease to acquired brain injury. Our aim is to help patients maximize their remaining vision so they may participate as fully as possible in activities that are important to them.

Functional vision

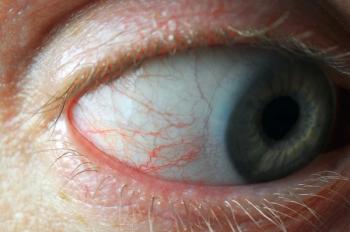

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, approximately 6 million Americans have vision loss (best corrected visual acuity of 20/40 or worse) and 1 million are legally blind (best-corrected visual acuity of 20/200 or worse). More than 1.6 million of these people are younger than 40.1

People with low vision are often told how much vision they have lost; our philosophy is to focus on the vision they have. To identify assistive devices that best match an individual's needs, we start with the simplest technology and work up to those that are more complex. If a person is looking to be able to read information, whether books, package directions, instructions, bills, or bank statements, we might start with traditional magnification. For patients whose vision loss has progressed from mild to moderate or severe, more advanced devices will be required. It is important to keep in mind that contrast sensitivity as well as visual acuity can be reduced. Vision tests in the clinic might be high contrast, but the world is not.

We concentrate on the functional component of patients' vision, no matter their visual acuity measurement, and how it can be improved with assistive technology. This means matching the choice of device to patients' goals and their ability to participate in activities that are important to them. We also consider comorbidities that go along with vision loss like arthritis or a tremor that can make it difficult to hold or stabilize a device. In addition, we need to understand a patient's cognitive ability and ensure a device is not too complex. In other words, we look at our patients holistically when we evaluate them for assistive technology.

Diagnostic tools

For our evaluation, we use several diagnostic tools that are not common in a standard eye examination. While traditionally clinicians measure patients' best-corrected visual acuity at a distance, we are more concerned with their near vision. By using a reading acuity test, we can assess the minimum print size a patient can read, as well as critical print size or the size at which one's reading skills are maximized. We measure contrast sensitivity function using charts that reveal how well a person can see print as it becomes fainter.

We perform microperimetry to determine macular integrity as many of our patients have reading difficulty due to common conditions like age-related macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy. We track the eye to precisely identify scotomas, localizing them to educate patients on potential workarounds to access more of their usable vision.

Changing technology

Assistive device technology has advanced well beyond traditional video magnifiers, what previously had been called closed-circuit televisions, to cutting-edge products that allow patients to bypass the use of their vision and rely on other senses instead. Some of these newer tools use increasingly sophisticated optical character recognition (OCR) software that recognizes and discerns characters and words so they can be read aloud. Some leverage artificial intelligence (AI), allowing devices to interpret data in real-time, even allowing users to ask clarifying questions for specific information that assists in not only reading but also in navigating and interacting with the world.

The demographic using sophisticated technology has also changed over time. Previous generations did not grow up using digital devices and, therefore, have been less willing to adopt new technologies. Today's baby boomer population prioritizes independence and is eager to continue doing the activities that they value. If this means learning how to use a new piece of technology, they are all for it.

Patients with moderate to severe vision loss require simple-to-operate devices. This means having a limited number of buttons so they can rely on feel and visual memory to guide them. Our facility has a variety of technologies available for patients to try. If an option we have on hand is not a good fit, we work to identify a more suitable technology, help patients order the product, and train them on its use.

Our patients are our priority; therefore, our goal is always to ensure that the assistive device we recommend is appropriate and usable. We do the research and legwork upfront to understand the available options, making sure we stay current on technology by attending conferences and meeting with vendors. My team is continuously updating what is available in our clinic for demonstration.

Leveraging AI: OrCam MyEye and the new Read 3

An excellent example of how assistive device companies are leveraging AI is OrCam’s MyEye device. We have long used MyEye, which is a wearable, voice-activated visual impairment solution for patients looking to navigate their environment in an interactive way. The latest AI-enhanced version can read text from books and screens, recognize faces, identify products and scan barcodes, verify monetary amounts, and recognize colors, communicating the information in real time. The device's AI Assistant feature provides users real-time assistance to maneuver around locations and in social situations by audibly describing what’s in a room. It responds to open-ended queries so users can obtain specific information and employs facial recognition software to assist with person-to-person communication. Its sophisticated features make MyEye appropriate for patients with very limited or no vision.

An AI-driven device that has been valuable to our patients with mild to moderate vision loss is the Read 3, also by OrCam. The Read 3 functions as a handheld reading companion, a smart magnifier, and a stationary reader that allows individuals to easily engage with printed and digital text and other visual materials.

Students, in particular, enjoy Read 3 because it pairs with AirPods or other earphones and allows them to keep up with their classmates when they need to read text. It helps them more fully participate in their schoolwork as well as the activities they enjoy outside the classroom. The device can be synced with any WiFi-enabled device, and its magnifier feature allows users to zoom in on text, handwriting, math equations, and images.

Read 3 also has been a valuable tool for our patients with a brain injury or reading disability. If, for example, reading is a challenge due to a brain injury that limits eye movements or causes eyes to fatigue easily, patients can rely more heavily on the audio while still following along with the text. The pause function is useful for patients with acquired brain injury who use it to follow directions. For example, while cooking, users can ask the Read 3 to read one step of a recipe, pause while they complete it, then restart and pick up at the next step. This is just one example of how assistive technology allows patients to perform daily activities that allow for more independence.

The Read 3 device can respond to voice commands, summarize text, and search text for specific information with its Just Ask feature. Imagine a patient with limited vision receives a bill containing superfluous verbiage when they only wish to know the amount and date due. Previously with OCR only, the user would have to listen to all the details to eventually get to the essential information. With the AI Smart Read function, the patient can ask it to look for specific information and read only that portion. This option saves time and effort, making patients more inclined to use the device.

Conclusion

From digital magnifiers to OCR to AI, assistive devices for patients with low vision have undergone a dramatic evolution. Today's tools empower patients with low vision to more easily read and navigate the world in ways that address their individual needs. The future application of these tools is limitless as machine learning increases in complexity, AI advances, and accuracy improves. I would encourage clinicians to partner with low vision services and providers in their area and make referrals. With the technology available today, low vision patients are able to live a rich and more independent life full of the activities that are meaningful to them.

Reference:

Prevalence estimates—vision loss and blindness. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. October 31, 2022. Accessed January 10, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/visionhealth/vehss/estimates/vision-loss-prevalence.html

Articles in this issue

almost 2 years ago

Meibomian gland dysfunction: At-home treatment devicesalmost 2 years ago

IKA Keratoconus Symposium: Traversing new groundalmost 2 years ago

As at-home dry eye treatments boom, the importance of compliance risesalmost 2 years ago

Annexon outlines 2024 strategy for ANX007 for geographic atrophyalmost 2 years ago

Multifocal contact lens optics optimize the patient experiencealmost 2 years ago

Beyond pharmaceuticals: Slowing the progression of AMD via nutritionalmost 2 years ago

What motivates you and your patients in myopia management?almost 2 years ago

How to get the most out of topical glaucoma therapiesNewsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.