How to determine treatment for a patient with a Roth spot

Discovering the underlying cause of a white-centered hemorrhage is key to management

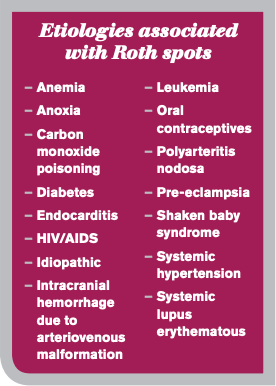

Occasionally, the primary-care OD may encounter a Roth spot, or a white centered hemorrhage. Classically associated with bacterial endocarditis, leukemia and anemia, these lesions are actually linked to a myriad of systemic conditions, often leaving the provider wondering what tests should be ordered or what systemic work-up is needed.

The following is a case of a patient who presented with a Roth spot and the subsequent management.

Case report

A 55-year-old male presented to the clinic for a comprehensive eye exam with a chief complaint of blurry vision at distance and near with his habitual bifocal glasses.

His pertinent medical history included hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus for approximately 10 years. He had been on medications for his diabetes previously but was taken off a few years ago; he now controled his diabetes with diet and exercise.

Incoming acuities were 20/20 OU with correction. Pupils were normal with no afferent pupillary defect, extraocular muscles were full OU, and full to finger counting on confrontation OD and OS. Slit-lamp examination of the anterior segment was unremarkable OU, and intraocular pressures (IOP) were 18 mm OD, OS.

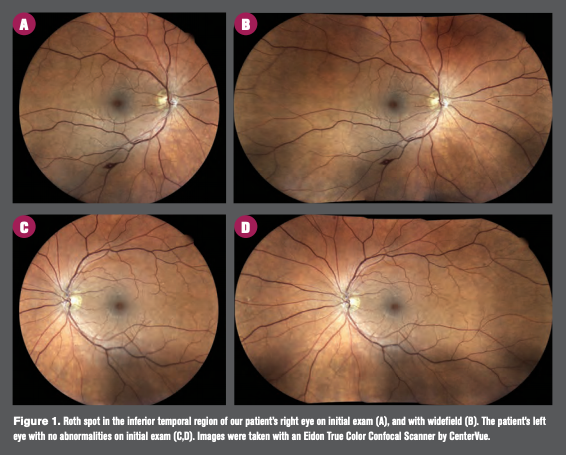

Dilated examination showed normal vessel caliber OU, rim tissue was pink and healthy, and margins were distinct OU with cup-to-disc ratio of 0.35 rd OU. Posterior pole revealed a few small dot blot hemorrhages OU with a solitary white centered hemorrhage in the inferior temporal arcade OD. Based on clinical appearance (Figure 1), it was diagnosed as a classic Roth spot.

Related: Roth spots show as initial presentation in multiple myeloma

Based on retinal findings, labs were ordered, including a complete blood count (CBC) and diabetes panel. Lab results showed an elevated A1c at 7.4 percent (normal range 4.2 to 5.8), glucose was also high at 137 mg/dL (normal range 70 to 110 mg/dL), and monocyte percentage was slightly elevated at 10.9 percent (normal range 2.0 to 10 percent). All other findings were normal.

His blood pressure was measured in-office as 131/84 mm Hg. The patient had a recent echocardiogram, performed approximately six months previously, which was normal per physician note. The patient was referred back to his primary-care physician who re-initiated oral treatment for his diabetes and discussed ways to lower the patient’s blood pressure.

The patient returned for dilated fundus examination (DFE) follow-up visit three months later with no subjective complaints. Upon dilated examination, the white centered hemorrhage had completely resolved. The patient also continued to deny fever, shortness of breath, or recent infections.

Based on the review of systems, lack of acute symptomology, medical history, and lab test results, it was determined the isolated white centered hemorrhage was likely associated with the patient’s diabetes. The patient was scheduled for a six-month return visit.

Discussion

A Roth spot is any round to slightly oval hemorrhage with a solitary, homogenous, paler, round center completely surrounded by the hemorrhage.1

Background

Early investigators thought the white centers represented infected embolic foci of septic infiltrates or represented a concentration of leukocytes, which is true in cases of leukemia and in some cases of bacterial endocarditis.2 However, the white center actually represents a fibrin-platelet thrombus.3 It typically results from the rupture of retinal capillaries and the extrusion of whole blood.

Under normal circumstances, retinal capillary endothelium is impermeable to the transmission of whole blood, but with any anoxic event or sudden elevation in venous pressure, or both, the capillaries rupture and whole blood is extruded.4

Subsequent reparation leads to platelet adhesion and coagulation cascade at the site of the damaged endothelium and results in the formation of a fibrin-platelet thrombus.3 Morphologically, this thrombus appears as a pale white lesion in the center of the hemorrhage.

A diverse list of conditions can lead to retinal capillary rupture and result in white-centered hemorrhages (see box). They can be subclassified according to underlying mechanism, such as thrombocytopenia, elevated venous pressure (Valsalva phenomenon), ischemia, or capillary fragility.2,4

Related: As seen on TV: Doing harm, not help, to the ocular surface

Thrombocytopenia is often associated with subacute bacterial endocarditis and acute leukemia, in which the body cannot produce ample platelets and leads to internal and external bleeding.5

Elevated venous pressure is seen with mothers who have undergone traumatic deliveries, neonatal birth trauma, battered children/shaken baby syndrome, intracranial hemorrhage from arteriovenous malformation, or prolonged intubation during anesthesia.6

Ischemic events can include anemia, anoxia, or carbon monoxide poisoning.4

Capillary fragility, as is the case with our patient, is often associated with diabetic retinopathy, hypertensive retinopathy, oral contraceptives, or idiopathic cases.6

Incidence with diabetes

White-centered hemorrhages are relatively common to see in cases associated with diabetes.

In one particular study, 215 diabetic patients (430 eyes) with early proliferative retinopathy, moderate to severe non-proliferative retinopathy, and/or diabetic macular edema in each eye were evaluated for the presence of such white-centered hemorrhages.7

The study found that 15.6 percent of these eyes demonstrated at least one white-centered hemorrhage, and 4.9 percent of the eyes showed five or more white-centered hemorrhages. In addition, there was no statistically significant difference in incidence of macular capillary injury between those with and without concurrent white-centered hemorrhages.7

Related: AI may be the answer for early disease detection

The study also found that there was no significantly higher prevalence of systemic or hematologic disorders in patients with diabetic retinopathy and white-centered hemorrhages.7

More specifically, there was no statistically significant difference between patients with and without white-centered hemorrhages in regard to the presence of increased systolic or diastolic pressure, hemoglobin levels, leukocyte counts, platelet numbers, increased serum creatinine values, or abnormal coagulation profiles.7

Differential diagnosis

Even though our patient’s Roth spot presented other retinal findings consistent with diabetic retinopathy, it is still imperative to rule out all other possible etiologies for the isolated white-centered hemorrhage before concluding capillary fragility as a result of diabetes mellitus as the most likely culprit.

Owing to the plethora of possible etiologies for the white-centered hemorrhage, it is imperative to match symptomatology, ocular signs, laboratory tests, and confirmatory results in order to reach a proper underlying diagnosis.

Related: Dry eye signs may signal risk for diabetic foot ulcers

For example, symptoms including fever, weakness, ecchymosis, hematuria, and/or infections along with ocular signs of white-centered hemorrhages, tortuous engorged vessels, vitreous hemorrhage, retinal detachment, retinal edema, and cotton wool spots, would indicate necessary lab testing with CBC with white blood cell (WBC) differential to rule out acute leukemia. A normal or decreased WBC count and WBC differential showing predominantly immature cells would definitively confirm such diagnosis.1

Common diabetes symptoms include weakness, weight loss, polyphagia, polydipsia, and/or polyuria. Ocular signs include diabetic retinopathy, fluctuations in refractive error, diplopia, optic atrophy, optic neuritis, and white-centered hemorrhages. Lab tests imperative to perform include fasting blood sugar and glucose tolerance test.1

Management

Given our patient’s lab results of elevated blood glucose, personal medical history, and lack of acute infectious symptoms, it was appropriate to assume the underlying etiology was diabetes mellitus for the isolated white-centered hemorrhage.

The primary-care physician was notified of this retinal finding to consider the possibility of re-initiating medication for his diabetes, which is what ultimately happened.

Management for Roth spots is influenced by their underlying cause. The optometrist should refer patients to the appropriate physician in order to treat the underlying disease process.

However, there is no specific treatment for the white-centered hemorrhage itself; it usually self resolves within six weeks.8 Patients who present with these non-specific lesions require a prompt comprehensive evaluation to determine the cause. Once it is determined, treatment for the underlying etiology is the priority.9

Conclusion

Our patient’s isolated presentation of a Roth spot showcases the strong link between ocular and systemic health. Although there is no specific treatment for the lesion itself, it is of paramount importance that the clinician promptly performs a thorough review of systems and orders the appropriate lab testing to determine the lesion’s underlying etiology and initiate treatment for that condition.

More by Steven Ferrucci: AMD genetic testing could lead to early diagnosis, better treatment

References:

1. Erneston AG, Bradford MB. Clinical laboratory analysis of white-centered hemorrhages. J Am Optom Assoc. 1986 Aug;57(8):617-20.

2. Fred HL. Little black bags, opthalmoscopy, and the Roth spot. Tex Heart Inst J. 2013;40(2):115-6.

3. Ling R, James B. White-centred retinal haemorrhages (Roth spots). Postgrad Med. J. 1998 Oct;74(876):581-2.

4. Duane TD, Osher RH, Green WR. White centered hemorrhages: Their significance. Ophthalmology. 1980;87(1):66-9.

5. Cleveland Clinic. Thrombocytopenia. Available at: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/14430-thrombocytopenia. Accessed 10/30/19.

6. Törnqvist G, Mártenson PA. Retinal white-centered hemorrhages in infectious mononucelosis. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1997 Feb;75(1):99-100.

7. Catalano RA, Tanenbaum HL, Majerovics A, et al. White centered retinal hemorrhages in diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmology. 1987 Apr;94(4):388-92.

8. Dell’Arti L, Barteselli G, Pinna V, et al. Sudden occurrence of Roth spots and retinal hemorrhages following endoscopic adhesiolysis: an SD-OCT evaluation. Eur J Opthalmol. 2015 Dec 1;26(1):e11-3.

9. Javaheri M, Bertoni B, Eliott D. White-centered retinal hemorrhages. Consultant 360. 2012; 52(8). Available at: https://www.consultant360.com/article/white-centered-retinal-hemorrhages. Accessed 10/30/19.

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.