- July digital edition 2024

- Volume 16

- Issue 07

Keeping patient care personalized

An introduction to cerebral visual impairment.

Cerebral visual impairment (CVI) encompasses an extensive range of visual impairments resulting from complications in the visual centers and pathways inside the brain, as opposed to dysfunctions in the eye itself.1 This impairment can occur due to a range of diseases, including neurological disorders such as cerebral palsy, head trauma, infections, and birth complications.1,2

CVI includes several kinds of visual manifestations, including reduced visual acuity, restricted visual field, challenges in visual attention and identification, and limited visual processing.2 The severity and nature of visual symptoms can significantly differ across individuals and may not always be evident during routine eye examinations.

Addressing CVI

The visual impairments reported by patients with CVI may not be adequately addressed by conventional vision correction treatments such as glasses or contact lenses, as the condition primarily affects the brain. As a result, treatment interventions frequently prioritize implementing techniques intended to maximize the individual’s residual visual capacity. These strategies encompass the utilization of visual aids, adjustments to the environment, and therapeutic approaches designed to enhance visual processing and functional vision abilities.3

Often, a multifaceted approach is required, incorporating the expertise of optometrists, pediatric ophthalmologists, teachers, occupational therapists, social workers, and neurologists. These medical and nonmedical professionals collaborate to provide comprehensive care tailored to each patient’s needs.

A range of risk factors can lead to CVI, with many of these variables involving disorders or events that affect brain development. Several prevalent risk factors linked to CVI include birth complications such as premature birth and perinatal hypoxia or ischemia.1 Postbirth circumstances can also lead to CVI, such as head trauma, stroke, or the development of neurological conditions.

It is crucial to remember that not all patients who have 1 of these risk factors will develop CVI.

Furthermore, it is important to note that CVI can manifest even in the absence of recognized risk factors, with the specific manifestations and severity of the condition varying significantly among affected patients. Early diagnosis of these risk factors leads to appropriate medical intervention to alleviate the potential impact of these factors on visual development.2

Assessment and diagnosis

A proper assessment is needed to obtain a formal diagnosis, starting with a thorough evaluation of a patient’s visual capabilities and limitations conducted by health care specialists with CVI knowledge. Exams specifically designed for individuals with CVI include functional vision examinations.2 Professionals who can aid in this process include pediatric ophthalmologists, low-vision optometrists, and neurologists.4

After obtaining a diagnosis, assisting patients with CVI requires a comprehensive strategy that tackles their unique visual difficulties and enhances their overall growth and well-being. The following are several methods and interventions that have demonstrated potential benefits for those diagnosed with CVI:

Reduction of visual clutter. One of the most common characteristics of CVI is difficulty with visual clutter. This can be observed from a very young age. Optimizing a patient’s environment by reducing visual clutter and complexity can enhance their capacity to navigate their surroundings.

These measures may involve reducing interruptions, employing uniform and simplified visual signals, and guaranteeing optimal lighting conditions.5 For example, a child’s toys can be separated by color into different bins, or reading materials can be equipt with larger font and more space between letters and sentences.

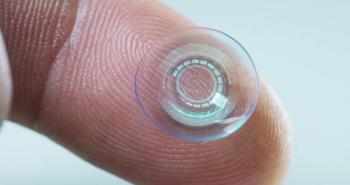

Introduction of visual aids. Patients with CVI can enhance their visual capabilities with visual aids and assistive devices such as Humanware Connect handheld and digital magnifiers. These devices that allow the student to see words written on the board more easily by enhancing contrast with the colors used on digital and printed material, and filters can cut glare and increase contrast.6

Integration of mobility training. Orientation and mobility training for patients with CVI can augment their capacity to navigate various surroundings safely and independently. This process may encompass several strategies, including spatial awareness training, learning different landmark cues, and using mobility aids such as canes or tactile indicators. A common struggle for those with CVI is going down the stairs due to visual neglect or deficiencies in the inferior portion of their visual field.1 Practicing this skill with an orientation and mobility specialist can help patients increase their confidence.

Participation in therapy programs. Vision therapy programs that are customized to address the unique requirements of individuals with CVI have the potential to enhance many visual abilities, including visual attention, tracking, and visual processing.3 These programs may incorporate exercises to increase visual capabilities and improve visual integration. Some patients with CVI can struggle with following movement or tracking a complete sentence when reading, and vision therapy can aid with that.1

The patient’s community must be involved to optimize their lifestyle. First, educational assistance is necessary for pediatric patients. Engaging in collaborative efforts with educators and specialists to design personalized education plans can effectively address the academic requirements of those diagnosed with CVI. This may entail adapting instructional methodologies, offering alternative media for educational resources, and integrating visual aids into the curriculum. Optometrists, ophthalmologists, and neurologists can write a detailed letter of recommendation for the patient to advocate for their needs.

Recommendations include but are not limited to the following:

- Adjusting the size and type of font used for educational material.

- Increasing contrast for printed and digital material.

- Having the student sit at the front of the classroom.

- Having a separate toy bin.

- Designing cues around the school building if the patient struggles to go down stairs or bumps into doors and walls.

Second, providing information, resources, and support to caregivers is crucial for the distinct requirements of individuals with CVI. Having written instructions and verbal conversations helps family members properly advocate for the patient. It is also important to stress that CVI is not a one-time diagnosis and resolution, as there is no cure for the disorder. As the patient’s needs inevitably change, the interventions must also be modified. There should be continuous collaboration with teachers, eye care providers, therapists, and caretakers for an optimal outcome.

Implementing these methods and interventions in a manner tailored to the patient’s specific needs would be highly beneficial. It is imperative to assist those with CVI in maximizing their visual potential and improving their overall functioning and quality of life.

References

Cortical visual impairment. Boston Children’s Hospital. Accessed June 18, 2024. https://www.childrenshospital.org/conditions/cortical-visual-impairment#symptoms--causes

Cerebral visual impairment (CVI). National Eye Institute. Updated November 15, 2023. Accessed June 18, 2024. https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/eye-conditions-and-diseases/cerebral-visual-impairment-cvi

6 steps to take after a CVI diagnosis. CVI Now/Perkins School for the Blind. Accessed June 18, 2024. https://www.perkins.org/6-steps-to-take-after-a-cvi-diagnosis/

How to find a doctor who is able to evaluate for and diagnose CVI. CVI Now/Perkins School for the Blind. Accessed June 18, 2024. https://www.perkins.org/how-to-find-a-doctor-who-is-able-to-evaluate-for-and-diagnose-cvi/

Bennett R. CVI: impact of clutter. CVI Now/Perkins School for the Blind. Accessed June 18, 2024. https://www.perkins.org/cvi-impact-of-clutter/

Connect 12 – smart portable HD magnifier, 10x distance viewing. HumanWare. Accessed June 18, 2024.

https://store.humanware.com/hus/connect-12-smart-portable-hd-magnifier-10x-distance-viewing.html

Articles in this issue

over 1 year ago

A beginner’s guide to dry eye treatment integrationover 1 year ago

Infrared imaging is an aid for patient education about GAover 1 year ago

Optometrists sing to the tune of advocacy in 2024over 1 year ago

Global dry eye by the numbersover 1 year ago

Stability is an important quality in toric lensesNewsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.