- July digital edition 2021

- Volume 13

- Issue 7

Low vision rehab in diabetic vision loss

Refer patients who have reduced vision and functional vision goals

Eye care practitioners often talk about medical management of patients experiencing vision loss due to diabetic retinopathy. However, they don’t talk as often about how these patients can be helped by visual rehabilitation with assistive devices or other means. Also, the point at which referral to low vision specialists occurs for many of these patients is blurred. Part of the predicament with low vision referrals concerns the instability of a patient who is experiencing a chronic disease with fluctuations in visual acuity and functional vision.

Richard Shuldiner, OD, FAAO, who has low vision expertise, offers his input on the following case studies regarding an appropriate time to intervene and what can be done. These advanced cases, presented in summary form, may appear unusual. However, such cases are commonly encountered in our patient population.

Case 1: ANOTHER POOR ADHERENCE TO FOLLOW-UP

A 65-year-old White woman returns because of recent changes in vision in her right eye after being lost to follow-up for 6 years. She has type 2 diabetes and systemic hypertension. According to the patient, her blood sugar averages 125 mg/dL.

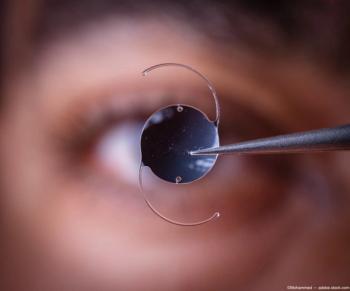

Four years ago, her visual acuities were OD 20/20 and OS 20/200. Her fundus examination, fluorescein angiography and optical coherence tomography (OCT) can be seen in Figure 1. She was undergoing intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) therapy during that time to manage her severe diabetic macular edema. She did not keep her follow-up appointments: She thought vision in her right eye had improved well enough despite the macular edema and the fact that vision in her left eye was not improving. However, the edema was improving upon OCT and clinical examination.

On her return, her best-corrected visual acuity was 20/200 OD and 20/400 OS. Her most bothersome symptom is seeing floaters caused by a vitreous hemorrhage (Figure 2).

As evidenced by her OCT scans, the patient continues to exhibit macular edema, which has worsened in both eyes. Additionally, chronic subretinal fluid from severe macular edema in the left eye has resulted in a large choroidal neovascular membrane and subretinal fibrosis.

Anti-VEGF therapy is recommended to eradicate the chronic macular edema. Panretinal photocoagulation is recommended for the proliferative disease in the right eye.

Although the right eye has a chance for improved vision, overall her prognosis is guarded. Is this a potential patient for visual rehabilitation and low vision evaluation? If so, when should she be evaluated, and what is recommended?

Low vision response

This case is interesting from a low vision perspective because it appears that her only complaint is not based on function. Had she commented that she cannot read small print, see facial expressions, or enjoy TV or any other visual activity, she would absolutely be a candidate for a low vision evaluation. It may be that functional questions are not part of the case history when treating medical eye problems. If not, perhaps they should be. One possible question to ask would be, “Is your level of vision preventing you from doing things you want to do?”

Low vision is defined as fully corrected vision that is insufficient to do what you want to do. Therefore, a patient with low vision must have both reduced vision and functional visual goals.

This patient should be referred to a low vision specialist so she learns what other help is available. I would confront the challenge of the instability of her condition, which would be considered in recommendations for low vision aids. We would discuss the possibility of the devices requiring changes as her vision changes as well as the cost of such aids.

Individuals come to eye doctors and endure an amazing number of procedures, most of which are uncomfortable. They do this for 1 reason: They want to see. Ultimately, eye care providers’ job is to keep the patient functioning; so, although low vision aids may offer a temporary fix, it is better than the patient being unable to do the tasks they want to do.

Case 2: SAD, BUT IT TRULY IS A BLINDING DISEASE

A 56-year-old Black woman has had type 2 diabetes since 1997. She was first seen in 2018, when her vision was 20/25 in each eye. Fundus photographs show findings indicative of proliferative diabetic retinopathy: preretinal hemorrhages noted through asteroid hyalosis in the right eye, and notable retinal neovascularization and preretinal hemorrhages (Figure 3).

She received intravitreous anti-VEGF therapy in both eyes, followed by panretinal photocoagulation in each eye soon after. She was given a 1-month follow-up appointment. Instead, she returned 2 years later, in early 2020, with significant worsening of retinopathy, including macular involved tractional retinal detachment and visual acuity of counting fingers at 2 ft OD and 20/200 OS (Figure 4). Following intervention including pars plana vitrectomy, she reached nearly maximum therapeutic effect with visual acuities of hand motion OD and 20/200 OS. The limitation of vision recovery is primarily due to damage to the inner retinal ischemic alteration as well as irreparable damage to the outer segment as seen in the final OCT scan (Figure 4). What can be done for this patient in terms of visual rehabilitation and assistive devices?

Low vision response

Patients with 20/200 best-corrected visual acuity are usually easy to work with. Believe it or not, those with 20/40 are the most difficult. With 20/200, the patient cannot read small print and will have difficulty with medicine bottles and diabetic treatments such as insulin syringes. They will complain about watching TV and recognizing faces. Kitchen work as well as grocery shopping will be difficult. Mobility might be affected. Low vision rehabilitation is indicated. Magnification aids should be well accepted and help with near vision tasks. Handheld stand magnifiers and electronic magnification devices will help with the near challenges of reading mail and food labels, seeing medicine bottles, and filling syringes. Moderate plus lenses will help with kitchen work and hand crafts. Higher-power plus lenses will help the patient to read small print. Low-power spectacle telescopes, prescription or OTC, will increase her enjoyment of TV and seeing facial expressions.

Various filters might help with mobility and glare. In addition, the low vision doctor might suggest a referral to an occupational therapist for home modifications and nonoptical aids. Large print telephones, calculators, watches, and all kinds of kitchen devices are available. Bump dots on oven dials are useful for setting temperatures.

If mobility is questionable, a referral to a certified orientation and mobility instructor would be advisable. These instructors can teach cane travel and suggest other means for safe, independent travel.

At 20/200, being legally blind, this patient is eligible for services for the blind and visually impaired from the State Department of Rehabilitation, to which a referral would be made.

Conclusion

Referring patients with vision loss for low vision rehabilitation is now the standard of care, recommended by the American Academy of Ophthalmology in 2016.1 People want to see. Patients will travel and take time away from other activities to visit their eye doctors as often as necessary. They tolerate burning eye drops, very bright lights, and annoying “Which is better?” questions. They allow injections into their eyeballs and other procedures for 1 reason: They want to see. When eye care providers cannot prevent vision loss, they must not say, “Nothing more can be done” when the profession has experts who can help. The field of low vision rehabilitation is able to help those with any amount of vision loss, from low vision to no vision. Low vision specialists help with optical aids, electronic aids, nonoptical aids, and other rehabilitative methods to keep individuals functioning and independent. Eye care providers should ask 3 simple questions of every patient with vision loss:

– How does your vision problem affect your

daily activities?

– Has your vision problem caused you to give

up activities that are important to you?

– Would you like me to refer you to a doctor

who may be able to help you see better? These questions will guide eye care providers in knowing when to refer a patient for low vision rehabilitation. It is not the amount of visual acuity or visual field that determines the low vision referral. It is the loss of abilities that counts. For example, patients with 20/30 visual acuity may have lived with 20/15 all their lives. Now they must get twice as close to see signs when driving and are very uncomfortable. Low vision aids can help. Low vision rehabilitation is about function, independence, and the quality of life.

Reference

1. The Academy’s initiative in vision rehabilitation. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Accessed June 16, 2021. https:// www.aao.org/low-vision-and-vision-rehab

Articles in this issue

over 4 years ago

Quiz: OCT helps diagnose macular pathologyover 4 years ago

Gain new technology insight by partneringover 4 years ago

Komono brings new suns to its Illusions lineover 4 years ago

Moving beyond refractive error correctionover 4 years ago

How plant oils may help dry eyeover 4 years ago

Ongoing COVID-19 protocolover 4 years ago

OCT helps diagnose macular pathologyNewsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.

.png)