Q&A: What role do optometrists play in the treatment geographic atrophy?

Diagnose, monitor, comanage—optometrists support patients throughout all stages of the disease.

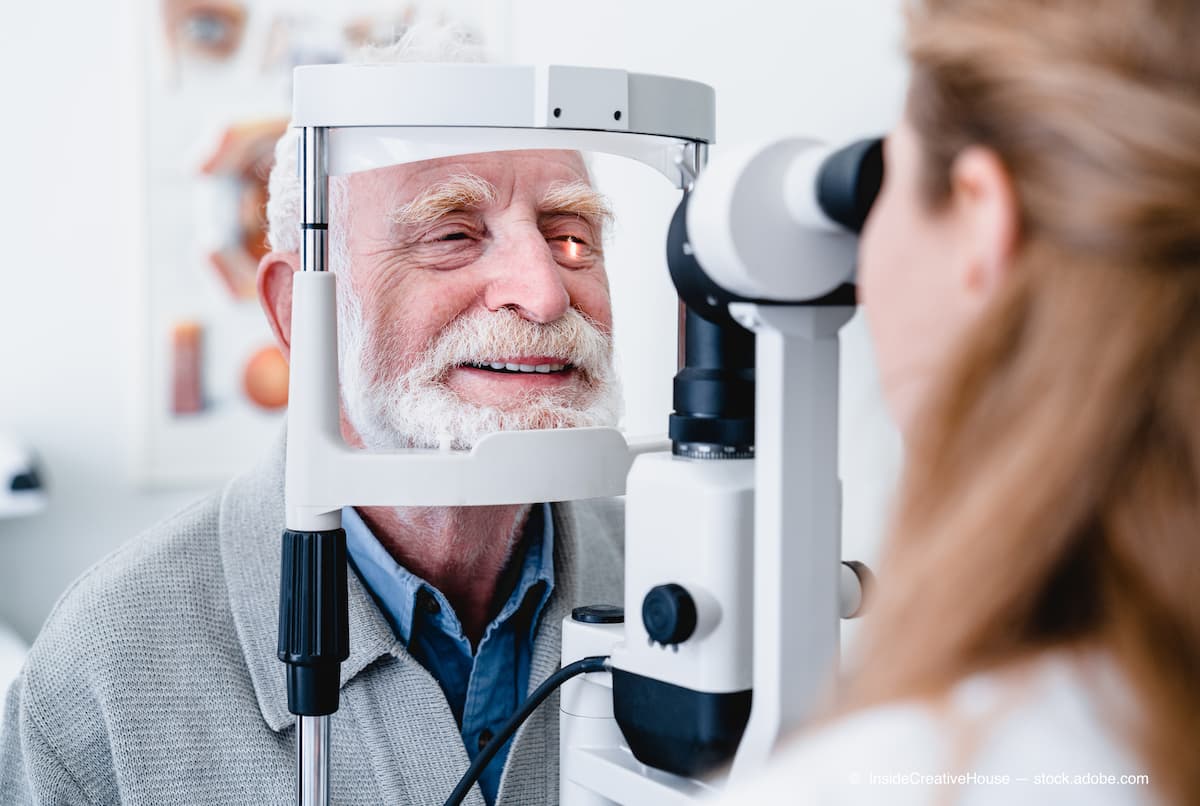

Optometrists have the most frequent touchpoints with patients and can identify candidates for treatment, and they are often the first to notice at-risk patients. (Adobe Stock/InsideCreativeHouse)

With the recent approval of pegcetacoplan (Syfovre; Apellis) and the pending review of intravitreal avacincaptad pegol (Iveric Bio), the treatment paradigm for geographic atrophy (GA) is shifting. Previously, there was no treatment available to slow lesion growth. Now that there are options entering the market, eye care must shift to meet the changing demands.

Steven Ferrucci, OD, FAAO, weighs in on how optometrists can lead the charge against geographic atrophy. From diagnosis to lesion growth monitoring, optometrists play a vital role in the management of the disease. Optometrists have the most frequent touchpoints with patients and can identify candidates for treatment, and they are often the first to notice at-risk patients.

Q: Can you tell me what optometrists can do to identify patients who are at risk for GA?

A: Patients at risk for GA would be very similar to those patients who are at risk for age-related macular degeneration (AMD) in general. Obviously, it would be older patients, patients with a family history of AMD or GA, patients with a history of smoking, and that sort

of thing. And after that, we would start to think about symptomatology.

To look for geographic atrophy, we’re going to do a comprehensive eye exam, with dilation, optical coherence tomography (OCT), and other ancillary tests, photos, etc, as needed. Some of the symptoms that patients report that might tip us off that the patient has GA, and they’re typically symptoms of impaired visual function such as scotomas, difficulty reading or losing their place when they’re reading, impaired facial recognition, reduced dark adaptation, and decreased contrast sensitivity. Visual acuity can be affected as well, but that tends to happen a little later in the disease, and visual acuity itself is probably not a good measure of geographic atrophy—especially early in the disease—because these patients will complain of visual function deficits before they start to complain about visual acuity reduction.

Q: Can you tell us how optometrists can leverage imaging in GA diagnosis?

A: There are multiple imaging techniques that can be used to look for GA. Fundus photography, OCT, and fundus autofluorescence are probably the 3 most common. Fundus photography is probably the most common because every optometrist I know has a retinal camera. You can obviously see the lesions in the loss of the RPE [retinal pigment epithelium] on the photography, but that’s probably not the best way to look for GA.

The best way is through OCT. These days most optometrists have OCT, which is good. There are 2 ways in my mind to do it. One is to look at the regular cross-sectional images that we typically look at, looking for any signs of what we call transmittance or transmission defects. Some [individuals] also call it a waterfall defect. That’s when you can see that the light from the OCT will penetrate more in the area where you have the GA lesion because you have loss of the retinal layers and loss of the RPE. So you’ll see more transmissions of light underneath a lesion. It’s a very easy way to find a GA lesion. You can also use the en face or the near-infrared imaging as well to look for lesions, and in my mind, that’s a good way to see [whether] they’re increasing in size.

The last thing is fundus autofluorescence, which is not as common and might not be used as commonly in the optometric practice, but it’s a good way to differentiate between inactive vs active lesions as well. But to me, OCT is the easiest way to look for lesions.

Q: What can optometrists do to improve partnerships with retina specialists in the care of patients with GA?

A: It’s important to have open communication. Now that we have an approved treatment for geographic atrophy, it’s going to facilitate even more comanagement between optometrists and retina specialists. If you always use the same retina specialist, talk to them. How do they see themselves using this in their practice? What type of patients with GA would they like to see?

I’m sure the retina specialists are going to be excited about the pegcetacoplan approval; they’re going to want to start treating these patients with GA. The majority of patients with GA are probably in optometric practices right now because there was previously no treatment for the disease, so there’s no reason that these patients would be referred to a retina specialist. But now that we have treatment, it’s important to diagnose GA and determine which patients might be best served by referral to the retina specialists and which patients might be good candidates for treatment.

I read an article about pegcetacoplan, and the headline mentioned that the drug slowed lesion growth but didn’t have a positive effect on visual acuity. While that may be true, it's somewhat misleading and doesn't tell the whole story. It’s important to note that the goal is to slow down progression of lesion size. And findings from the study showed it could be…up to 36% in 2 years. The real goal is to prevent lesion growth, which is going to decrease the number of visual symptoms patients have and help them be more independent over time. The goal isn’t necessarily better acuity, because a lot of these patients with geographic atrophy might not even have decreased acuity. So using acuity as a landmark for whom you should or shouldn’t refer or whether or not the patient’s benefiting from the treatment might not be the best thing. We have to think about visual function more so than visual acuity.

Q: Do you anticipate that the approval of pegcetacoplan will change the comanagement of patients with GA, and how do you expect it to change the treatment paradigm?

A: I do. In the past, if we had a patient with geographic atrophy, there was nothing we could do; we would watch their lesions get larger and watch their visual function decrease. But now we have an option for a patient. So if we see patients whose lesions are progressing, if they’ve already lost vision in 1 eye from geographic atrophy and we want to think about protecting the other eye, or if they have a family history of vision loss from geographic atrophy, these are going to be red flags for us.

It’s going to facilitate a lot more communication between optometry and ophthalmology. Retina specialists are already overwhelmed with the number of injections they’re doing for wet AMD, diabetic retinopathy, and vein occlusions. The pegcetacoplan approval is going to add even more patients. So we can help them comanage these patients, see the patients between visits, talk to the patients, look at their GA, check whether it is progressing more quickly. It’s going to be even more important as retina specialists get busier, and it opens the door for optometrists to be of assistance.

I was always under the impression that geographic atrophy was a relatively slow progressive disease. But findings from some of the studies that they’ve done looking at the natural history of GA point out that it’s not as slowly progressing as many of us might have thought. So you may think you have a lot of time to watch these lesions before thinking about treatment, but that might not be the case. I encourage optometrists to start looking for patients with GA and have a discussion with them that there is a treatment now. Again, really think about those types of patients who might benefit from early treatment.

Q: Do you have any thoughts on the upcoming Prescription Drug User Fee Act goal date of avacincaptad pegol from Iveric?

A: It’s always nice to have multiple treatment options. Time will tell which treatment option is the better treatment option, but it’s nice to have more tools for our patients, which will lead to better care of our patients overall.

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.