- November digital edition 2024

- Volume 16

- Issue 10

Rate my management: Diving deep into a case of glaucoma

Puzzle-piecing a new patient’s medical history together takes many forms.

What would you do? I do not mean for that question to be taken rhetorically. I would truly like to know what you would practically and tangibly do in the clinical vignette I will now lay before you. So, gather ‘round, children: It’s story time!

About a month and a half before I penned this column, a patient presented to me as a new glaucoma referral. He had recently moved to a suburb of my hometown from Atlanta, Georgia, and he had sought care at an optical chain on the other side of town. He was referred to my clinic because of his advanced glaucoma. When he was being taken from my waiting room for preliminary testing, I did what I like to do from time to time: I greet the patient casually in the hallway and pleasantly converse while I nonchalantly observe their gait, awareness of where they are in space, and their general movement. This man almost ran into more than one wall on his way to get pretested. I noted that he had been driven to his appointment that day.

When I got my eyes on his chart, he was noted to be a 68-year-old African American man with an approximate 20-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, a “longtime” history of systemic hypertension, and a “longtime” history of high cholesterol. He was taking metformin, hydrochlorothiazide, amlodipine, and atorvastatin as per a review of his e-prescribed medications, and he reported good medication adherence. He also reported good control of his blood chemistry, but didn’t check his blood sugar levels and thought the result of his last hemoglobin A1C test was somewhere around 7. He believed his last physical examination that included bloodwork was sometime earlier this year.

A review of the patient’s e-prescribed medications did not reveal any glaucoma medications. However, he stated he took 1 drop of an eye medication at nighttime and 2 drops a day of another one. After questioning him regarding the colors of the caps of these bottles, I determined that he used a prostaglandin analogue at bedtime and a β-blocker-containing combination drop in the morning and at bedtime in both eyes. He reported no known lung conditions or difficulty breathing and no known medication allergies. His pulse was 74 beats per minute at a regular rhythm.

Entering visual acuities through the patient’s habitual spectacle correction were 20/30 in each eye. He refracted to 20/20 in each eye with a low myopic astigmatic correction. Extraocular muscle testing showed a full range of motion for each eye, and confrontation visual fields showed constriction in all quadrants for each eye. Careful confrontation field testing with a penlight showed central visual field preservation and some temporal preservation for each eye. IOPs by means of Goldmann applanation and rebound tonometry were 8 mm Hg in the right eye and 9 mm Hg in the left eye at 10:15 am. The patient’s anterior segments were essentially unremarkable, shown to be open by means of the Van Herick method. The dilated posterior segment examination showed mild nuclear cataracts, a few areas of arteriovenous nicking, and optic nerves that were just about cupped out in their entirety.

I obtained optic disc photos, gave the patient an updated prescription for spectacles with polycarbonate lenses to be worn full-time, and pulled my chair back to have a brief conversation with him. The patient did not know how long ago he had been diagnosed with glaucoma, but he recalled it being well more than 20 years. He reported good adherence with his drops, but stated he went without his drops for “a while” several years ago due to lengthy hospital stays for his “heart issues.”

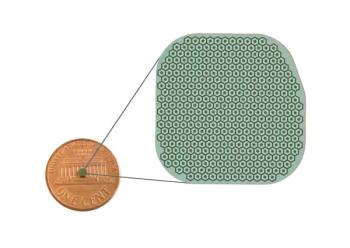

So, what did I decide on for this patient’s treatment? With what is currently clinically available for treatment, his IOPs are essentially about as low as IOPs can get. This is end-stage glaucoma, however, and this patient may progress despite having very low IOPs. We need to keep those low IOPs consistently low. I invited him back in a few weeks at a different time of day for another IOP check and baseline visual field testing. Thankfully, his IOP remained below 10 mm Hg in each eye at that second visit, which was in the afternoon. His angles were open to the ciliary body in each eye with mild pigment in his trabecular meshwork. His 24-2 visual field study was an unreliable blackout field, and I have invited him back again for a 10-2 visual field study. I think that will be the best way to stage his glaucoma moving forward. I made no changes to his medications and arranged for him to get established with a local primary care physician for his ongoing systemic health care. I also arranged for a low vision clinic to contact him. As of this writing, he has not yet had his 10-2 visual field study.

My relationship with this patient is in its infancy, and I have yet to be able to attain records from previous eye examinations. Given all of this information we have so far, would you manage this patient differently? Is there a variable we are not accounting for here? I will keep you apprised about this patient’s glaucoma; there are several medications coming down the pipeline that will be mentioned in my next column that may be of particular interest with respect to this patient’s care. In the meantime, reach out and let me know your thoughts.

Articles in this issue

about 1 year ago

Is there a relationship between keratoconus and diabetes?about 1 year ago

EnVisioning the future of eye careabout 1 year ago

The white cane and beyond: Part 2about 1 year ago

Understanding blue light: Making sense of the spectrumabout 1 year ago

The ABC's of cornea healthabout 1 year ago

Semifluorinated alkanes in dry eye diseaseNewsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.