- April digital edition 2021

- Volume 13

- Issue 4

The coming presbyopia revolution

New technology may be able to help ODs’ most challenging patient segment

Worldwide, 1.8 billion presbyopes exist, 826 million of whom are visually impaired because of inadequate vision correction.1 Although most Americans have access to near vision correction, many are not satisfied with the experience of presbyopia—or their options for correcting it.

By far, the most common solution is OTC reading glasses, worn by 33 million Americans.2 As an optometrist, I consider them to offer low-level correction, typically of poor optical quality with significant visual and convenience tradeoffs. A 2018 market research survey conducted by Alcon found that presbyopes did not like them much, either. More than two-thirds (67%) said they would prefer to stop adjusting their lives around their vision and their need for reading glasses.3 The onset of presbyopia carries many negative connotations. It is an early sign of aging that can pack an emotional punch. Patients find the sudden need to wear reading glasses or carry multiple pairs of glasses inconvenient and cosmetically unappealing.

Few presbyopes are offered contact lenses, however. A Gallup research poll in 2015 found that only 9% of adults over 40 years with vision correction were offered multifocal or monovision contact lenses when they complained about near vision problems.4 Lined bifocals or trifocals and progressive addition lens spectacles are more frequently offered despite interest from patients in reducing the need for spectacles.

Although my practice fits many multifocal contact lenses, barriers to success exist, particularly with emmetropes. I admit that I cringe when I have a 45-year-old patient who sees 20/15 uncorrected at distance and is “interested in contact lenses” because I know I have a slim chance of satisfying that patient with our current options. Fortunately, new technologies that have recently hit the market or are on the horizon could revolutionize the way ODs treat presbyopes in their practices.

Contact lenses

One of the barriers to prescribing multifocal contact lenses has been the lack of options for patients with astigmatism. About half of all contact lens wearers have astigmatism,5 which becomes harder to mask with the onset of presbyopia. Dissatisfaction with vision is as much a factor as comfort when it comes to contact lens discontinuation among presbyopes.6

In the past year, 2 toric multifocal contact lenses were introduced and should help to overcome that barrier: Ultra Multifocal for Astigmatism (Bausch + Lomb) and Biofinity Toric Multifocal (CooperVision). Both are daily-wear soft lenses with a monthly replacement schedule, and they are available in a wide range of parameters that allow ODs to fit most patients (Table 1).

Surgical options

Although patients can have laser in situ keratomileusis (LASIK), photorefractive keratectomy, or small incision lenticule extraction monovision, there has never been a “no-brainer” surgical option—and the industry still lacks one for the younger presbyope.

For older presbyopes who already have lenticular changes, I am more likely now to recommend early lens surgery than I would have been a decade ago. Optometrists who were deterred by the lackluster results of first-generation presbyopia-correcting (PC) intraocular lenses (IOLs) such as Crystalens (Bausch + Lomb), ReZoom (AMO), and ReStor (Alcon) or even the second-generation multifocal IOLs, should look at the excellent results achieved with the latest PC IOLs.

These include the first trifocal, PanOptix (Alcon), and the first extended depth-of-focus (EDOF) lens, Tecnis Symfony (Johnson & Johnson Vision), in the United States. Both lenses overcame challenges with intermediate vision and night vision dissatisfaction that plagued earlier PC IOLs, providing high rates of patient satisfaction.7-9

In the coming year, eye care practitioners will see a continuation of PC IOL innovation with the introduction of Johnson & Johnson Vision’s Tecnis Synergy, an EDOF-multifocal hybrid that is expected to provide better near vision, and Alcon’s low-add Vivity EDOF lens, which was just launched. A small-aperture IOL from AcuFocus in the pipeline has also shown impressive results10 and may be helpful for patients with irregular corneas.

PC IOL technology has reached a level that makes me confident in encouraging patients with cataract and those who are closer to needing cataract surgery to make this choice. But a clear lensectomy is still a big jump for a 45-year-old with residual accommodation who is frustrated with near vision. As far as PC IOLs have come, they still would not be my choice for most patients under age 60 years.

Pharmacological approaches

A number of pharmacological treatments for presbyopia are in phase 2 or 3 US clinical trials (Table 2), with several expected to become available within the next year. The potential for a topical treatment is very exciting. The drops in development are primarily miotic agents. These drugs, including pilocarpine, carbachol, and aceclidine, have well-established mechanisms of action and safety records. They increase depth-of-focus through the pinhole effect and activate the ciliary body for some accommodative effect, as well.

Some pupil-modulating agents, such as Allergan’s pilocarpine product (AGN-190584), are expected to be single-agent drops, whereas others combine the miotic agent with other drugs to mitigate adverse effects. Visus Therapeutics, for example, has been investigating a fixed combination of carbachol and brimonidine, which has the potential to prolong the pinhole effect to 8 hours, reduce the brow aches and headaches that have been associated with cholinergic agonists in the past, and whiten the eye at the same time.11,12

The great news is that pupil-modulating drops will likely be low risk and reversible, making them an easy option for patients to try. My expectation is that optometrists will be able to prescribe and, in some states, dispense pupil-modulating drops, which is a tremendous opportunity. Many patients who will be good candidates for these drops—emerging presbyopes in their 40s, post- LASIK emmetropes, those who cannot wear contact lenses or could not adapt to progressive lenses, and even pseudophakes who are not happy with reading glasses. Until ODs have more clinical data from the ongoing studies, exactly how presbyopia drops will fit into the armamentarium is difficult to predict, but I can envision the market being very broad.

Another category of topical therapies under development, most notably by Novartis, has the potential to alter crystalline lens proteins to soften the lens or prevent the effects of aging. Although these drops are still in the pipeline, investigators hope they will delay the effects of presbyopia and cataract.

As these innovative new drops come to market, ODs will need to learn more about their mechanisms of action, duration, and adverse effect profiles. ODs will also need to try them with their own patients to discover variability in patient response and determine how to counsel patients on drop frequency and administration.

Perhaps most exciting is that presbyopia drops have the potential to bring a whole new patient segment into optometric offices—emmetropic adults who haven’t had an eye exam in years (maybe never) because they didn’t need vision correction or were able to get by with drugstore readers. Not only is addressing this patient population a great practice growth opportunity, it is also a public health opportunity. Those emmetropes might have untreated dry eye, glaucoma, or macular degeneration. Their eyes may provide a clue to undiagnosed systemic conditions, such as diabetes or hypertension. Losing near vision may be what motivates emmetropic individuals to come into optometric offices, but presbyopia treatment is just the start of the care ODs can provide.

Refractive cross-linking

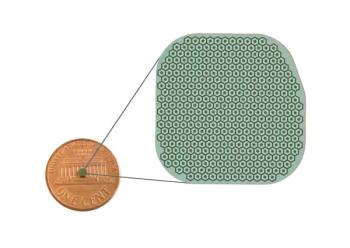

Corneal collagen cross-linking is now accepted as the standard treatment for progressive keratoconus and post-refractive ectasia. Outside the United States, cross-linking has been investigated for a range of applications, including myopia control, corneal stabilization prior to corneal refractive surgery, and presbyopia correction. Photorefractive intrastromal cross-linking for presbyopia is a monocular treatment in which a ring of tissue in the midperiphery of the cornea is cross-linked to produce central steepening for near vision.13 The procedure, which is performed with the Mosaic system (Glaukos), has been studied and performed commercially in Europe and Asia but will likely not be available for some time in the United States.

Conclusion

The future for presbyopia care is bright. Optometrists have new multifocal contact lenses and presbyopia-correcting IOLs, as well as multiple pharmacological agents in the pipeline for this previously underserved affected patient population. I believe eye care is on the cusp of a renaissance in presbyopia management, so this is a great time to start talking with patients about new and emerging developments.

References

1. Fricke TR, Tahhan N, Resnikoff S, et al. Global prevalence of presbyopia and vision impairment from uncorrected presbyopia; systematic review, meta-analysis, and modelling. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(10):1492-1449. doi:10.1016/j. ophtha.2018.04.013

2. Organizational overview. The Vision Council. Accessed February 28 2021. https://www.thevisioncouncil.org/sites/ default/files/TVC_OrgOverview_sheet_0419.pdf

3. Presby-what? new Alcon surveys show patients have fuzzy understanding of presbyopia; eye care professionals agree. News release. Alcon. April 5, 2019. Accessed February 11, 2021. https://www.alcon.com/media-release/presby-what-new-alcon-surveys-show-patients-have-fuzzy-understanding-presbyopia-eye

4. Review of Optometric Business/Bausch + Lomb. Capturing the presbyopic opportunity. 2016. Accessed December 22, 2020. https://www.bausch.com/Portals/77/-/m/BL/ United%20States/Files/Downloads/ECP/Vision%20Care/ BL-Multifocal-Supplement.pdf?ver=2016-07-28-103547-817

5. Young G, Sulley A, Hunt C. Prevalence of astigmatism in relation to soft contact lens fitting. Eye Contact Lens. 2011;37(1):20-25. doi:10.1097/ICL.0b013e3182048fb9

6. Rueff EM, Varghese RJ, Brack TM, Downard DE, Bailey MD. A survey of presbyopic contact lens wearers in a university setting. Optom Vis Sci. 2016;93(8):848-854. doi:10.1097/ OPX.0000000000000881

7. Pedrotti E, Carones F, Talli P, et al. Comparative analysis of objective and subjective outcomes of two different intraocular lenses: trifocal and extended range of vision. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2020;5(1):e000497. doi:10.1136/ bmjophth-2020-000497

8. Choi M, Im CY, Lee JK, Kim HI, Park HS, Kim TI. Visual outcomes after bilateral implantation of an extended depth of focus intraocular lens: a multicenter study. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2020;34(6):439-445. doi:10.3341/ kjo.2020.0042

9. Kohnen T, Herzog M, Hemkeppler E, et al. Visual performance of a quadrifocal (trifocal) intraocular lens following removal of the crystalline lens. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;184:52-62. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2017.09.016

10. Ang RE. Visual performance of a small-aperture intraocular lens: first comparison of results after contralateral and bilateral implantation. J Refract Surg. 2020;36(1):12-19. doi:10.3928/1 081597X-20191114-01

11. Abdelkader A, Kaufman HE. Clinical outcomes of combined versus separate carbachol and brimonidine drops in correcting presbyopia. Eye Vis (Lond). 2016;3:31. doi:10.1186/ s40662-016-0065-3

12. Stamper R, Lieberman M, Drake M. Becker-Shaffer’s Diagnosis and Therapy of the Glaucomas. 8th ed. Mosby Inc.; 2009.

13. Kanellopoulos AJ, Asimellis G. Presbyopic PiXL cross-linking. Curr Ophthalmol Rep. 2015;3:1-8. doi:10.1007/ s40135-014-0060-6

Articles in this issue

almost 5 years ago

Biologic medications: The basics that every OD should knowalmost 5 years ago

Should ODs get a COVID-19 vaccine and require staff to get vaccinated?almost 5 years ago

How to fit scleral lenses with confidence and cautionalmost 5 years ago

Quiz: How to fit scleral lenses with confidence and cautionalmost 5 years ago

Investigational agent aims to eradicate Demodex mitesalmost 5 years ago

Where golf and optometry meetings intersectalmost 5 years ago

News updates April 2021almost 5 years ago

5 glaucoma management mythsalmost 5 years ago

Treating sight-threatening retinopathy using OCTANewsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.