SD-OCT shows schisis advancements due to sickle cell

Retinoschisis can make diagnosing open-angle glaucoma especially difficult for optometrists.

Sickle cell disease is one of the most common genetic hemoglobinopathies in the United States, where it affects about 100,000 people.1

It is characterized by irregular and malfunctioning red blood cells which can cause anemia, vascular occlusion, and end-organ damage.1 The eye is both an end-organ and contains part of the central nervous system.

Potentially serious complications from sickle cell disease in the eye include ischemic retinopathy and subsequent neovascularization which can lead to retinal detachment and vitreous hemorrhage.2

An uncommon ophthalmic manifestation of this disease is retinoschisis, which is thought to be due to areas of relatively mild ischemia within the inner retina and subsequent intraretinal separation.3 Such a process may lead to glial proliferation and subsequent retinal traction, resulting in vision loss.4

Related: Year in review of optometric advancements

Case example

I have one patient whom I have been following as a suspect for primary open-angle glaucoma for about a decade who also has a diagnosis of sickle cell trait. Sickle cell trait means she inherited one copy of the normal hemoglobin (HbA) gene and one copy of the mutated hemoglobin

(HbS) gene.5

This 65-year-old African-American female is originally from the Caribbean. Her medical history is remarkable for chronic back pain and systemic hypertension, for which she is currently medicated with oxycodone-acetaminophen and hydrochlorothiazide, respectively. She also daily takes a 1 mg folic acid supplement and a 50,000 unit vitamin D capsule.

Her family history is significant for cataracts, open-angle glaucoma, diabetes, and hypertension. She has an uncle with glaucoma and several siblings who reportedly do not have glaucoma.

The patient is a low hyperope with moderate astigmatism for which she wears spectacles. Best-correct visual acuity to date is 20/20 OD and 20/25 OS. She exhibits a mild degree of eccentric fixation OS.

Her anterior segments have always been unremarkable, and she has a mild amount of nuclear sclerosis and cortical spoking in each lens.

Related: ODs: Redefine your role in glaucoma collaborative care

Back of the eye

I inherited this patient as a referral on the grounds of suspicion of glaucoma. Her initial presenting intraocular pressures (IOP) were 17 mm Hg OD and 18 mm Hg OS in the mid-morning. Those have been, to date, the highest IOPs I have measured, with IOPs typically running between 11 mm Hg and 15 mm Hg.

Since 2009, when I initially began seeing this patient, her optic nerves and retinal nerve fiber layers have not declined. Periodic visual field testing has also failed to show any frank glaucomatous defects. She has a central depression in her visual field OS which has been relatively stable.

Her optic nerves are of average size with vertical cup-to-disc rations of approximately 0.5. Her central corneas are of average thickness with values of 557 μm and 566 μm for the OD and OS, respectively. Her angles are open to ciliary body with flat approaches and mild to moderate pigment for all quadrants of each eye.

I last saw this patient in October 2019, and, to date, she has not converted to glaucoma.

When I first examined her in 2009, her entering visual acuities with her habitual spectacle correction were 20/25 in each eye. I documented her optic nerves with fundus photography and invited her back for ancillary glaucoma testing.

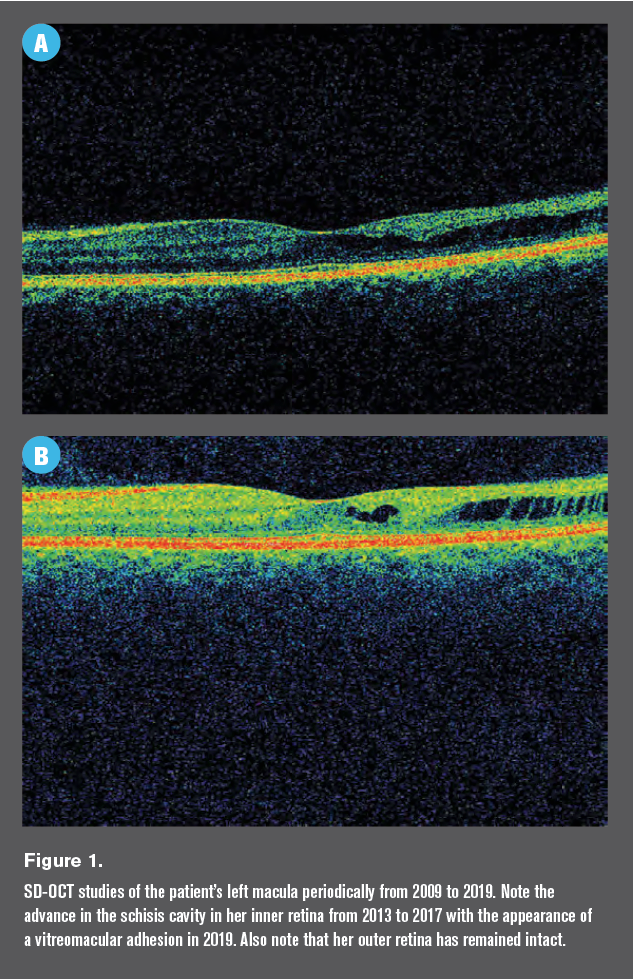

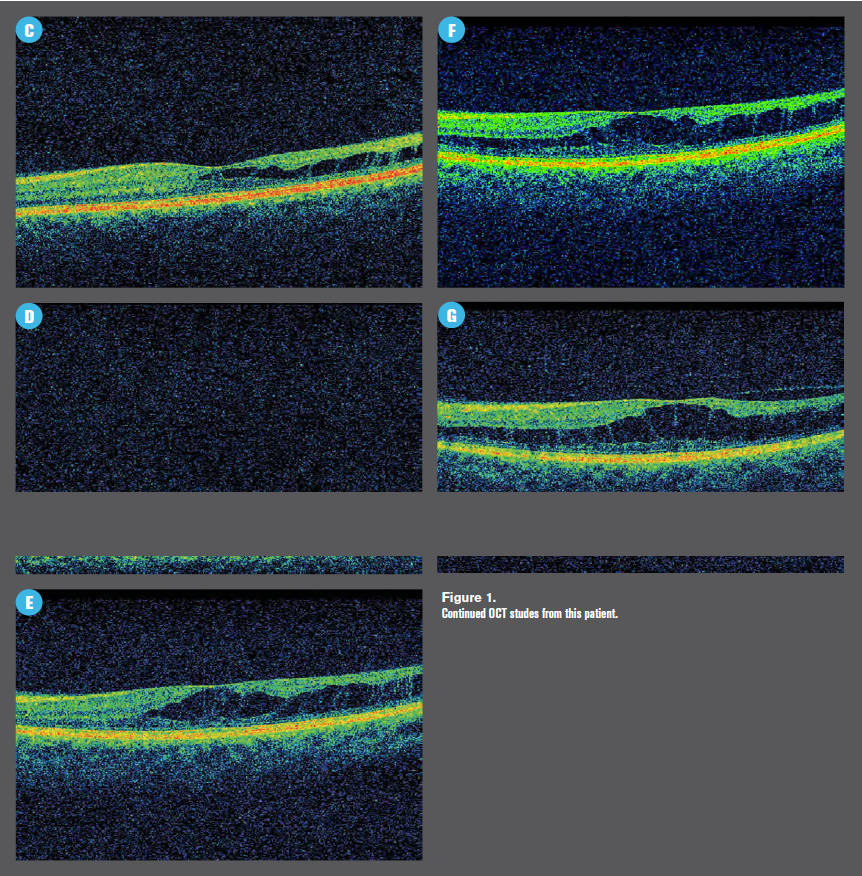

It was on spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) testing that I noted a mildly disorganized inner retina on the temporal aspect of her left macula (Figure 1).

Related: New research highlights how data is processed to detect glaucomatous optic neuropathy

Follow-up

I did not yet have SD-OCT software which included quantification of the ganglion cell complex, but I was performing macular scans on all glaucoma patients and glaucoma suspects with the notion that when I attained the software, it would be retroactive.

I advised that she check her vision in each eye independently every day and call me as soon as possible should any visual distortions occur.

I followed up with her every six months or so until 2013, when an unfortunate family event kept her away from receiving health care for several years.

Related: How ODs should break bad news to patients

When this patient presented again for follow-up care in 2017, her visual acuity was unchanged with entering corrected acuities of 20/25 in each eye. She had no complaints.

Her SD-OCT study at this visit was more impressive than her previous studies (Figure 1) with a high degree of inner retinal disorganization.

I obtained a consultation with a retina specialist in order to ensure that no treatment was necessary, and he referred her back to me for continued optic nerve monitoring; he sees her annually. Her last visit with him was June 2019.

Note that her SD-OCT study from 2019 shows an area of vitreomacular adhesion as well.

The retina specialist and I are in agreement that although schisis cavities are relatively rare complications of sickle cell trait, there is likely a connection between her left macula and her blood disorder.

More by Dr. Casella: Look at more than the optic nerve head in glaucoma patients

References:

1. Shah N, Bhor M, Xie L, Paulose J, Yuce H, Kamolz L-P. Sickle cell disease complications: Prevalence and resource utilization. PLoS One. 2019 Jul 5;14(7):e0214355

2. Shukla P, Verma H, Patel S, Patra PK, Bhaskar LVKS. Ocular manifestations of sickle cell disease and genetic susceptibility for refractive errors. Taiwan J Ophthalmol. 2017 Apr-Jun; 7(2):89-93.

3. Schubert HD. Schisis in sickle cell retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005 Nov;123(11):1607-9.

4. Carney M, Jampol L. Epiretinal membranes in sickle cell retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1987 Feb;105(2):214-7.

5. Gibson JS, Rees DC. How benign is sickle cell trait? EBioMedicine. 2016 Sep;11:21-22.

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.