New guidelines in OSD evaluation before surgery

OSD evaluation remains imperative before cataract referral, even in asymptomatic patients.

With all of the recent publications concerning dry eye disease, as well as updates on technology and pharmacologic agents to diagnose and treat it, many practitioners are tuning out of the conversation.

Whether they are overwhelmed by the amount of information to decipher, tired of hearing about it, or think the condition is being overemphasized to create revenue for industry, many optometrists are not eager to hear more about dry eye disease.

With that being said, dry eye disease is still being undertreated by optometrists and ophthalmologists alike. One facet of the patient population that is particularly being underserved is those being referred or evaluated for cataract surgery.

Related: Common systemic conditions associated with dry eye disease

Guidelines

Recent publications have underscored the importance of screening all patients for ocular surface disease prior to cataract surgery. The American Academy of Ophthalmology’s Dry Eye Syndrome Preferred Practice Pattern,1 published in 2018, recommends that “all patients undergoing cataract surgery should be evaluated and managed for dry eye preoperatively.”

In May 2019, the Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery published an article proposing new guidelines for how to pre-operatively evaluate and manage ocular surface disease (OSD).2 Christopher Starr, MD, and his colleagues on the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery (ASCRS) Cornea Clinical Committee propose that it is imperative to fully evaluate the health of the ocular surface before considering cataract surgery in all patients, even those who are asymptomatic.

They outlined a clinical assessment algorithm to be sure that “visually significant” OSD is diagnosed and treated prior to surgery until it is well-controlled, or “non-visually significant.” In the article, the ASCRS claims that “by treating OSD preoperatively, postoperative visual outcomes and patient satisfaction can be significantly improved.”

Undiagnosed dry eye

Although experts agree that controlling dry eye pre-operatively is a must, it has previously been reported in literature that dry eye disease is often left undiagnosed prior to cataract surgery.

In a 2018 prospective study, Gupta et al found that 50 percent of asymptomatic patients evaluated for cataract surgery had an abnormal tear osmolarity or matrix metalloproteinase (MMP-9) levels, both positive indicators of OSD.3

The Prospective Health Assessment of Cataract Patients’ Ocular Surface study (PHACO), published in 2017, concluded that 15 to 20 percent of patients evaluated for surgery would have remained undiagnosed if they had not had a full ocular surface evaluation. Furthermore, they determined that it is necessary to perform multiple test in order to identify OSD.4

Cataract surgery and the ocular surface

But what is the harm to patients if they are not diagnosed and treated prior to cataract surgery? Can’t we just manage the side effects afterwards?

One important reason to treat prior to surgical evaluation is that unresolved dry eye disease results in poorer visual outcomes for patients. Precise preoperative measurement of the cornea is critical to minimizing refractive error postoperatively. The cornea is responsible for approximately 70 percent of the total refractive power of the eye, so accurately assessing its’ power is key to selecting the correct intraocular lens (IOL) power.5

Related: Recognize signs and treatment for patients with persistent PSP

Chuang et al published a review of recent studies in the Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery in 2017.6 They concluded that “an impaired ocular surface affects preoperative planning for cataract surgery.” They proposed that unresolved dry eye reduces the repeatability of keratometry and topography measurements, thereby reducing the accuracy of IOL calculations. They conclude that diagnosing and treating dry eye prior to surgery will result in better visual outcomes for patients.

Gibbons et al completed a retrospective review of patient cases over a five-year time period to determine the causes of patient dissatisfaction with presbyopia-correcting IOLs. They published their results in Clinical Ophthalmology in 2016, concluding that the leading cause of patient dissatisfaction with cataract surgery due to preoperative causes was dry eye disease. They also found that 57 percent of patient dissatisfaction due to postoperative causes was due entirely or in part to uncorrected refractive error.7

Another key reason to proactively identify and manage dry eye preoperatively is that cataract surgery has been shown to both cause and worsen dry eye disease. If eyecare practitioners identify, treat, and educate these patients prior to surgery, the patients will understand that postoperative symptoms are due to their disease. If practitioners do not address dry eye preoperatively, the patient is much more likely to place the blame on us for their symptoms.

Related: Treat dry eye disease first, address comfort next

Dry eye post surgery

A recent study by Cetinkaya et al found that Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) scores, fluorescein staining, and tear break up time (TBUT) all worsened in the month following cataract extraction.8

In another study, Chuang et al found that 87 percent of dry eye patients became symptomatic after surgery, with half of these patients exhibiting corneal staining.9 Prospective studies found an increase in patient dry eye symptoms, a decrease in tear meniscus height and Schirmer’s test scores, a decrease in tear film break-up time (TBUT), an increase in corneal staining, and a loss of conjunctival goblet cell density within three months postoperatively.6

These studies report that symptoms occur as early as one day after surgery, peak between one week and one month, then diminish over time. Increased duration of the surgery correlated with worsened dry eye. Additionally, cataract surgery has been shown to worsen meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD).

A study by Han et al found that patients who had undergone cataract surgery exhibited a reduction in meibum secretion and increased meibomian gland obstruction, along with physiological changes at the lid margin such as vascular telangiectasia. These changes were noted at one month postoperatively and had not resolved at three months after surgery.9

There are many factors which contribute to dry eye disease after cataract surgery.

Chuang et al, in their 2017 review of studies, cite several mechanisms for the development or exacerbation of dry eye postoperatively, including:6

– Frequent use of topical ocular medications before and after surgery

– Use of povidine-iodine solution for sterilization

– Prolonged exposure of the ocular surface to a microscope light during surgery

– Damage to corneal nerves caused by incision

– Aggressive irrigation of the eye during surgery

Related: IPL treats rosacea and meibomian gland dysfunction

Cataract evaluation testing

The ASCRS Preoperative OSD Algorithm recommends that an OSD Screening include three elements:2

– Patient questionnaire

– Tear film osmolarity

– Ttesting for inflammatory markers (MMP-9)

Related: Go beyond medical treatment for recurrent corneal erosion

Step 1

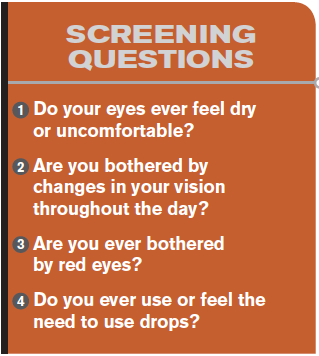

The first step in identifying patients with ocular surface disease is asking the right questions.

Dry eye patients often have been living with their symptoms for a long time and feel they are “normal.” They often do not report symptoms without prompting, so having a standard patient questionnaire is critical in finding these patients.

There are many options to assess patient symptomology, including Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI), Standard Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness (SPEED), and even the less complex Dry Eye Summit 2014 questions (see box).10

The ASCRS Guidelines recommended the use of a SPEED II Preop OSD Questionnaire, which was modified from the original SPEED specifically for use with preoperative patients.

Which method you use doesn’t matter as long as you utilize a thorough and uniform tool to elicit patient symptoms.

Step 2

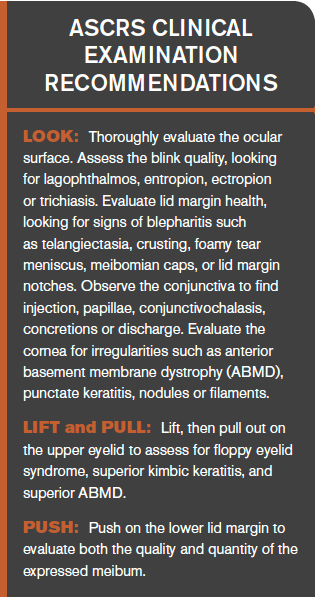

The second step is to make sure you are looking for signs of ocular disease with the slit lamp. The ASCRS algorithm considers tear film osmolarity and MMP-9 testing to be extremely “essential data” in diagnosing ocular surface disease.

However, if these tests aren’t available, you can still find many of these patients with a thorough inspection of the ocular surface. Look carefully at the lid margins for signs of meibomian gland dysfunction, such as telangiectasia, erythema, fine crusting of the lashes, or changes in lid morphology like notching or loss of lashes.

Press on the lid margin with your finger tip, a cotton swab, or a tool such as a Korb evaluator (Tear Science/Johnson & Johnson Vision) to assess gland function and the quality of the meibum. Observe the quality of the tears, especially looking for foamy tear meniscus, a sign of MGD.

Finally, use fluorescein to look for staining of the cornea and/or conjunctiva. Also, evaluate the tear meniscus height to look for aqueous deficient dry eye disease. The ASCRS developed a helpful mnemonic for clinicians evaluating cataract patients preoperatively: “Look, Lift, Pull, and Push” (see box).2

Do not refer the patient for cataract evaluation until the corneal surface is healthy and the patient is comfortable.

Treat the patient prior to referral if:

– There is any ocular surface damage (staining)

– The patient has dry eye affecting the quality of vision (e.g. has to blink to see clearly

– The patient has significant symptoms (SPEED>8)

The ASCRS committee considers OSD to be “non-visually significant” once the cornea is smooth and free of staining or irregular astigmatism and the patient’s vision no longer fluctuates.

Once you feel certain the patient’s dry eye is “non-visually significant,” it is important to educate the patient prior to referral. Advise her that her dry eye is likely to worsen after surgery, but that you will help her to manage it so she remains comfortable throughout the postoperative period.

Related: How the blink affects contact lens wear

Case report

A 58-year-old white female presented with complaints of blurred vision and her eyes being dry, red and burning, especially after prolonged video display or monitor use. Pertinent exam findings were:

– Best-corrected visual acuity 20/60- OD and OS

– 2+ nuclear sclerotic cataracts

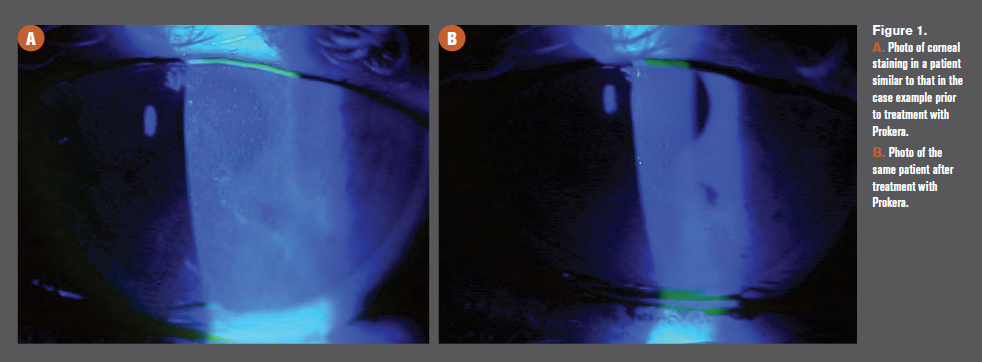

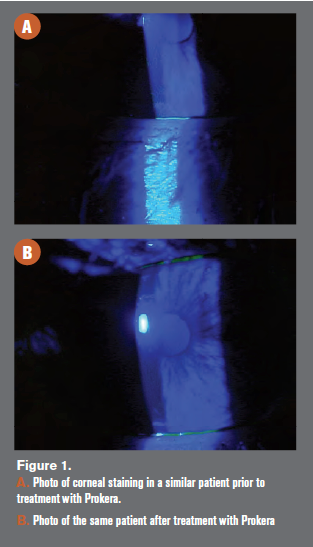

– 1+ superficial punctate keratitis OU, > inferiorly

– Tear film break-up time 3 to 4 seconds

She was started on an initial therapy of Retaine MGD Q1-2H, warm compresses, and blink exercises (frequent breaks with intentional, firm blinking), especially while using the video display terminal and was scheduled for a full dry eye evaluation.

Related: The possible connection among kids, devices, and myopia

This evaluation yielded the following results:

– SPEED 15/28

– Tear osmolarity normal (293 OD and OS)

– MMP-9 positive

– Tear film break-up time 2 to 3 seconds

– 2+ superficial punctate keratitis

– Cloudy meibum

The patient was prescribed Xiidra (lifitegrast, Novartis) bid and 2,000 mg omega-supplement daily. At her follow -visit in six weeks, the patient’s symptoms had improved (SPEED 4/28), but she still had 2+ superficial punctate keratitis and reduced tear film break-up time, with a positive InflammaDry test (Quidel).

The patient was eager to resolve her dry eye quickly so she could have the cataracts removed, so it was decided to place a Prokera Slim (BioTissue) amniotic membrane graft to promote corneal healing. The Prokera was placed in one eye at a time for three to four days each.

At the final visit to remove the Prokera, her superficial punctate keratitis was resolved entirely in both eyes and her best-corrected visual acuity had improved to 20/40 OD and 20/50 OS. The patient was referred for cataract evaluation. Postoperatively, she achieved OD 20/20- and OS 20/25+ unaided visual acuity, was satisfied with the results and had no complaints of ocular discomfort.

Related: Blood-derived serum tears go beyond conventional therapy

References:

1. Akpek EK, Amescua G, Farid M, Garcia-Ferrer FJ, Lin A, Rhee MK, Varu DM, Musch DC, Dunn SP, Mah FS; American Academy of Ophthalmology Preferred Practice Pattern Cornea and External Disease Panel. Dry Eye Syndrome Preferred Practice Pattern. Ophthalmology. 2019 Jan;126(1):P286-P334.

2. Starr CE, Gupta PK, Farid M, Beckman KA, Chan CC, Yeu E6, Gomes JAP, Ayers BD, Berdahl JP, Holland EJ, Kim T,

Mah FS; ASCRS Cornea Clinical Committee.An algorithm for the preoperative diagnosis and treatment of ocular surface disorders. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2019 May;45(5):669-684.

3. Gupta PK, Drinkwater OJ, VanDusen KW, Brissette AR, Starr CE. Prevalence of ocular surface dysfunction in patients presenting for cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2018 Sep;44(9):1090-1096.

4. Trattler W, Majmudar P, Donnenfeld D, McDonald MB, Stonecipher KG, Goldberg DF. The Prospective Health

Assessment of Cataract Patients’ Ocular Surface (PHACO) study: the effect of dry eye. Clin Ophthalmol. 2017 Aug 7;11:1423-1430.

5. Courville CB, Smolek MK, Klyce SD. Contribution of the ocular surface to visual optics.. Exp Eye Res. 2004 Mar;78(3):417-25.

6. Chuang J, Shih KC, Chan T, Wan KH, Jhanji V, Tong L. Preoperative optimization of ocular surface disease before cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2017 Dec;43(12):1596-1607

7. Gibbons A, Ali TK, Waren DP, Donaldson KE. Causes and correction of dissatisfaction after implantation of presbyopiacorrecting intraocular lenses. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016 Oct 11;10:1965-1970.

8. Cetinkaya S, Mestan E, Acir NO, Cetinkaya YF, Dadaci Z, Yener HI. The course of dry eye after phacoemulsification surgery. BMC Ophthalmol. 30 Jun 2015;15(68):1-5.

9. Han KE, Yoon SC, Ahn JM, Nam SM, Stulting RD, Kim EK, Seo KY. Evaluation of dry eye and meibomian gland dysfunction after cataract surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014 Jun;157(6):1144-1150.e1

10. Caffery B, Devries D, Dunbar M. Improving the Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Dry Eye Disease: Recommendations From The 2014 Dry Eye Summit. Rev Optom. Available at: https://www.reviewofoptometry.com/

publications/improving-the-screening-diagnosis-andtreatment-of-dry-eye-disease. Accesed 1/17/19.

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.