Back to the basics: Understanding methods for measuring visual acuity

Visual acuity remains an important indication of ocular and visual health.

Image credit: AdobeStock/nenetus

Measuring visual acuity (VA) is one of the first skills that eye care professionals learn during their training, as it is among the most important measures of an individual’s ocular and visual health. Health care practitioners can more consistently assess a patient’s condition or visual status when they use standardized VA measurements, such as Snellen 20/20 or logMAR units.1 These data are essential for determining whether there are any underlying eye issues.

Most frequently, VA tests aid in identifying any refractive errors that require the use of spectacles or contact lenses to improve VA. The degree of myopia, hyperopia, astigmatism, or presbyopia could be assessed with the magnitude of visual acuity deficit. Corrective lenses should ideally completely restore the patient’s VA. If glasses or contact lenses fail to fully correct a patient’s eyesight, it is necessary to identify and adequately justify an ocular health deficit as the cause of the impaired vision.

For patients receiving treatments such as anti-VEGF injections,2 laser treatments,3,4 and therapeutic eye drops,5 tracking VA would test for the efficacy of these treatments. The goal of most ocular treatments is to maintain or improve a patient’s vision, so assessing the effectiveness can be done by measuring VA. In the case of decreasing VA, the physician could opt to either change the prescribed therapeutic treatments or provide additional treatments.

Assessing a patient’s VA also remains significant because a certain degree of visual acuity is necessary for many tasks, including driving and applying for jobs as a pilot or military personnel. To verify that a person can safely complete the required duties or to renew licenses, optometrists can assess VA.

All things considered, VA testing is an essential instrument for evaluating a patient’s eye health and, if necessary, for pursuing interventions to increase acuity.

Methods for assessing VA

VA can be assessed by many methods, which this article will provide a few examples of. When determining the most appropriate method, we consider aspects including age, necessity, clinical setting, and degree of VA impairment.

The Snellen chart is the most commonly utilized exam. It consists of rows of letters that diminish in size from top to bottom. Patients often read letters from a standard distance of 20 feet or 6 meters, with results documented using the commonly used notation of “20/20” or “20/40.”6

Image credit: AdobeStock/magr80

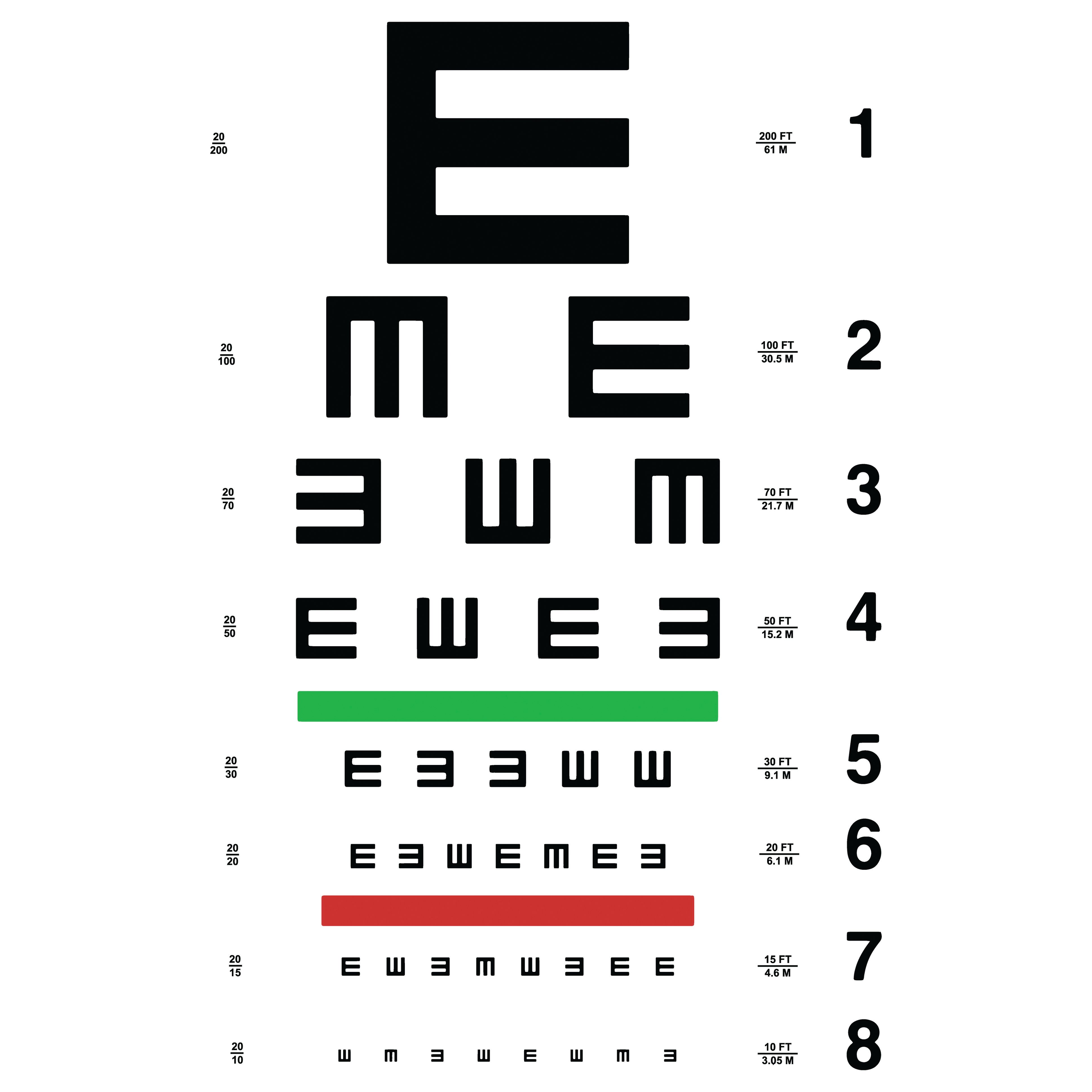

Another often-used chart is the logMAR chart, which decreases in size similarly to the Snellen chart but has more uniform letter progression and spacing (Figure 1). It is utilized more frequently in research or clinical trials than in clinical environments due to the more reliable systematic variations in font size and spacing. Low-vision clinics frequently utilize logMAR charts, as Snellen charts typically lack sufficient optotypes for larger letters.7

Image credit: AdobeStock/magr80

The Tumbling E chart and Landolt C charts are analogous techniques that employ various orientations of the letters E and C, and are suitable for patients who are nonverbal, illiterate, or nonnative speakers, or those who struggle to read letters on conventional Snellen or logMAR charts. Patients can vocally or physically indicate the orientation of the E or the position of the gap in the C (ie, up, down, left, or right) (Figure 2).

Methods for pediatric visual acuity testing

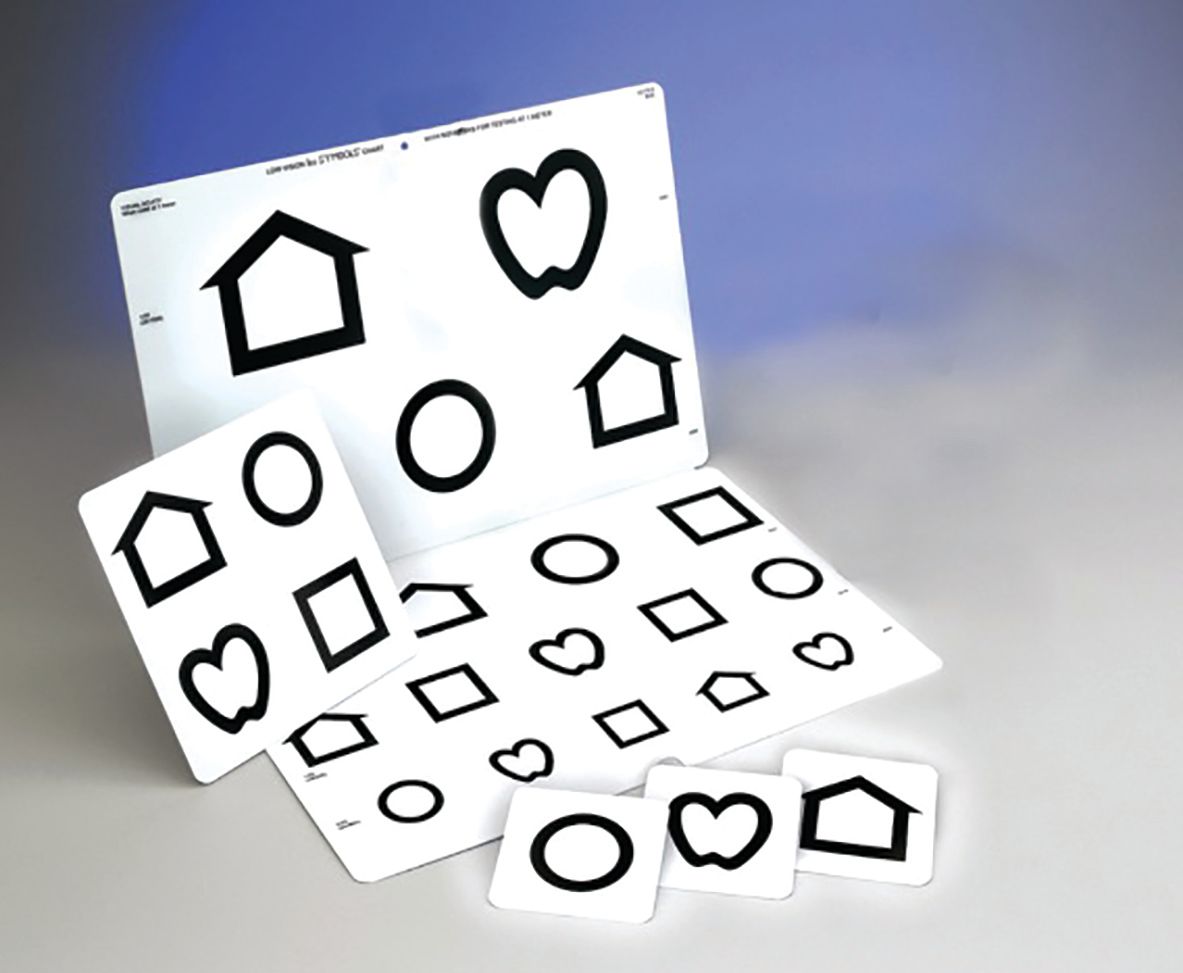

Image credit: Bernell

Because infants and toddlers cannot read letters, picture charts such as LEA Symbols (circle, square, apple, home) are employed for verbal identification or matching by the patient. It offers a child-centric methodology that facilitates engagement for children (Figure 3).

The Teller Acuity Cards offer a specialized method for assessing VA in infants and toddlers, generally for patients younger than 2 years old or those who are unable to communicate verbally. The principle of preference staring posits that newborns and early children are inclined to gaze at visually stimulating patterns (specifically high-contrast designs such as stripes).8

Image courtesy of Candice E. Clifford-Donaldson, MPH; Breann M. Haynes, BSN; and Velma Dobson, PhD.

Each card features 1 striped side and 1 blank side, enabling the examiner to evaluate the child’s gaze direction. It assesses spatial resolution (the capacity to discern fine detail) without necessitating verbal communication or sign recognition from the pediatric patient. It is valuable for assessing visual function in infants, children with developmental disabilities, or anyone unable to complete traditional VA assessments (Figure 4).

The future

The measurement of patients’ VA will likely remain an essential component of patient care for the foreseeable future. However, the technique used to acquire this information may gradually transform as technology continues to rapidly evolve in the digital age.

Testing for visual acuity remotely is becoming more and more common, and it was particularly prevalent in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.9 There are a variety of methods available for testing visual acuity through video chat during remote eye exams and follow-up visits. It is no longer necessary to bring bulky, cumbersome VA charts when visiting underserved or rural areas because there is a plethora of apps available for both iOS and Android platforms that enable calibrated visual acuity testing on smartphones and tablets.10

Virtual reality headsets will likely create an immersive testing environment for VA, contrast sensitivity, stereo, visual field, and other skills. Similarly, the optometric field anticipates the use of smart glasses, which may integrate with electronic health record systems to streamline data transfer.

The bottom line

The objective of improved acuity testing methods and adaptive technologies is to facilitate more accessible patient care across various language barriers and disabilities. The future of visual acuity assessment is expected to be more accurate, user-centric, and tailored to individual requirements. These innovations will promote the early diagnosis of visual impairments, optimize vision correction, and eventually improve quality of life by allowing practitioners to offer highly individualized and accessible eye care. The future of eye care will undoubtedly incorporate methods to foster a more inclusive and equitable approach, beginning with more flexible techniques for assessing VA.

References:

Schwiegerling J. Field Guide to Visual and Ophthalmic Optics. SPIE Press; 2004.

Wykoff CC, Garmo V, Tabano D, et al. Impact of anti-VEGF treatment and patient characteristics on vision outcomes in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Opthalmol Sci. 2024;4(2):100421. doi:10.1016/j.xops.2023.100421

Ivandic BT, Ivandic T. Low-level laser therapy improves vision in patients with age-related macular degeneration. Photomed Laser Surg. 2008;26(3):241-245. doi:10.1089/pho.2007.2132

Durrie D, Stulting RD, Potvin R, Petznick A. More eyes with 20/10 distance visual acuity at 12 months versus 3 months in a topography-guided excimer laser trial: possible contributing factors. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2019;45(5):595-600. doi:10.1016/j.jcrs.2018.12.008

Ohira A, Hara K, Jóhannesson G, et al. Topical dexamethasone γ-cyclodextrin nanoparticle eye drops increase visual acuity and decrease macular thickness in diabetic macular oedema. Acta Opthalmol. 2015;93(7):610-615. doi:10.1111/aos.12803

Levenson JH, Kozarsky A. Visual acuity. In: Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, eds. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 3rd ed. Butterworth Publishers; 1990.

Oduntan AO. A practical logMAR near reference table for low vision practitioners: Design and applications. S Afr Optom. 2006;65(4):157-162. https://doi.org/10.4102/aveh.v65i4.271

Joo HJ, Yi HC, Choi DG. Clinical usefulness of the teller acuity cards test in preliterate children and its correlation with optotype test: a retrospective study. PloS One. 2020;15(6):e0235290. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0235290

Massie J, Block SS, Morjaria P. The role of optometry in the delivery of eye care via telehealth: a systematic literature review. Telemed J E Health. 2022:28(12):1753-1763. doi:10.1089/tmj.2021.0537

Suo L, Ke X, Zhang D, et al. Use of mobile apps for visual acuity assessment: systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2022;10(2):e26275. doi:10.2196/26275

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.