- January/February digital edition 2025

- Volume 17

- Issue 01

Debunking myths about keratoconus

Misconceptions often lead to missed diagnoses.

I have been caring for patients with keratoconus (KC) for 30 years. During that time, technology and the standard of care have improved. However, the nuances of early diagnosis can still be tricky to understand. One way to address this is by debunking some of the myths and misconceptions regarding KC.

Myth 1: Patients with 20/20 vision can’t have KC.

Vision worse than 20/20 can be a red flag for KC, but it isn’t the only factor, just like IOP isn’t the only factor relevant to a glaucoma diagnosis. In fact, diagnosing and treating KC before the patient has lost vision is the ideal scenario. Snellen visual acuity tells us only about visual quantity—how many black letters the patient can read on a white screen. However, what our patients really care about is their quality of vision, which can be affected quite early in the disease. A patient with monocular diplopia from KC may miss critical information on signs, for example, even though they can technically discern enough letters to read 20/20 on an eye chart. Visual acuity is not part of the definition of KC, and falling below a certain threshold of acuity requirement is not a qualification for treatment with corneal collagen cross-linking.

Myth 2: You can’t detect KC without topography/tomography.

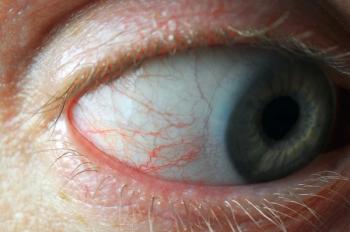

It is true that the gold standard for diagnosing KC is tomography, which can measure both the front and back surfaces of the cornea.1 Not every optometric office has tomography (or topography), but that doesn’t mean optometrists aren’t empowered to detect KC. A good history and simple tools that optometrists routinely use, such as refraction, keratometry, and retinoscopy, can provide all the necessary clues (Table). If indicators are present (Figure 1), the patient can then be referred for further testing to confirm the diagnosis.

Once you suspect KC, ensuring that you refer the patient to the right person is the most important next step. Ideally, the patient should be referred to an ophthalmologist who performs iLink cross-linking (currently the only cross-linking procedure that is FDA approved) or to an optometrist who fits specialty contact lenses. Both of these types of providers will have the advanced diagnostic tools needed to monitor progression, be well versed in documenting progression for insurance, and be able to either schedule the patient for cross-linking (if indicated) or send them to a partner who can. Too often, I have seen patients get stuck in a chain of referrals to providers who don’t fit specialty contact lenses or perform cross-linking. By the time they get to the right person, they may have had multiple appointments, each of which required several weeks of wait times, and their condition may have progressed further. I’ve even seen it take years for patients to find their way to a treating practitioner.

Myth 3: If you suspect KC, it’s OK to wait and follow up with your patient over time, especially if they are older.

Progression can occur at any age, so a “wait-and-see” approach is not recommended. Instead, schedule a follow-up visit in a timely fashion. Although rapid progression is most likely to occur in young patients, Kollros et al recently reported on significant progression in patients older than 48 years.5Several reports have demonstrated that a substantial proportion of patients can progress very quickly, losing lines of vision within 6 to 12 months or even sooner.6-9 For this reason, it is important to quickly refer patients to a cross-linking or a specialty contact lens provider for further evaluation if advanced imaging is not available in-house. Once progression is observed, prompt treatment with corneal cross-linking is needed to reduce or stop further progression and preserve good visual acuity, according to the American Academy of Ophthalmology’s Corneal Ectasia Preferred Practice Pattern guidelines.10

Myth 4: Rigid contact lenses stop the progression of KC.

Patients will often tell me that their doctor sent them to me for “hard” lenses that will prevent their KC from getting worse. Although a contact lens can temporarily flatten the cornea, it cannot prevent a genetic condition from further manifesting. For example, it is commonly understood that the reason cataract surgeons require those who wear gas-permeable (GP) lenses to stay out of their lenses for several weeks before surgery is that the impact of the GP lens on the cornea is not permanent. The only way to prevent permanent corneal changes is with corneal collagen cross-linking. In a recently published study, 100% of the KC eyes treated with iLink corneal cross-linking remained stable 10 years after treatment.11

GP lenses neutralize much of the distortion or optical aberration of the anterior corneal surface. They do an excellent job of correcting irregular astigmatism in patients with KC. However, there is evidence that a flat-fitting corneal GP lens can actually harm an ectatic cornea12—and it won’t arrest the progression of KC.

Myth 5: Scleral lenses are sufficient for KC treatment.

As compared with corneal GP lenses, scleral lenses can provide superior vision and allow for better centration, a larger optical zone, and less corneal desiccation.13 Most importantly, for a KC eye, they don’t touch the cornea. In short, scleral lenses can do an excellent job of optimizing fit and vision for patients with KC (Figure 2). Patients may mistakenly conflate good vision with good ocular health. It is our job to educate them that KC is a progressive corneal disorder that will get worse if left untreated. The appropriate treatment for progressive KC is cross-linking.14 Although cross-linking and scleral lens fitting can be performed in any order—depending on life circumstances, time needed for insurance review, or provider availability—the urgency to intervene before additional progression is paramount.15

Myth 6: Corneal cross-linking is a cash-pay procedure.

For patients with health insurance, the FDA-approved iLink cross-linking is typically a covered service. When an unapproved device or riboflavin is used to perform transepithelial cross-linking, patients are unable to use their insurance and may incur significant out-of-pocket costs. In addition, the safety and efficacy of unapproved drugs or devices have not been established. A meta-analysis suggests that non–FDA approved transepithelial cross-linking has been inferior in efficacy to the standard epithelial-off protocols approved for use in the US.16 Among pediatric patients treated with transepithelial cross-linking, 50% had to be retreated due to significant deterioration and/or functional regression after 12 months.17 New cross-linking systems under development may successfully address the weaknesses of transepithelial cross-linking, but it is important that these systems go through the FDA investigational new drug vetting process to ensure patients are treated effectively. Referring to doctors who perform unapproved, cash-pay cross-linking may have risks for the patient and could incur medicolegal risks for the referring doctor.

References

1. Gomes JA, Tan D, Rapuano CJ, et al. Global consensus on keratoconus and ectatic diseases. Cornea. 2015;34(4):359-369. doi:10.1097/ICO.0000000000000408

2. Asimellis G, Kaufman E. Keratoconus. StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

3. Santodomingo-Rubido J, Carracedo G, Suzaki A, Villa-Collar C, Vincent SJ, Wolffsohn JS. Keratoconus: an updated review. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2022;45(3):101559. doi:10.1016/j.clae.2021.101559

4. Hashemi H, Heydarian S, Hooshmand E, et al. The prevalence and risk factors for keratoconus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cornea. 2020;39(2):263-270. doi:10.1097/ICO.0000000000002150

5. Kollros L, Torres-Netto EA, Rodriguez-Villalobos C, et al. Progressive keratoconus in patients older than 48 years. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2023;46(2):101792. doi:10.1016/j.clae.2022.101792

6. Shah H, Pagano L, Vakharia A, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on keratoconus patients waiting for corneal cross linking. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2021;31(6):3490-3493. doi:10.1177/11206721211001315

7. Chatzis N, Hafezi F. Progression of keratoconus and efficacy of pediatric [corrected] corneal collagen cross-linking in children and adolescents. J Refract Surg. 2012;28(11):753-758. doi:10.3928/1081597X-20121011-01

8. Goh Y, Gokul A, Yadegarfar ME, et al. Prospective clinical study of keratoconus progression in patients awaiting corneal cross-linking. Cornea. 2020;39(10):1256-1260. doi:10.1097/ICO.0000000000002376

9. Romano V, Vinciguerra R, Arbabi EM, et al. Progression of keratoconus in patients while awaiting corneal cross-linking: a prospective clinical study. J Refract Surg. 2018;34(3):177-180. doi:10.3928/1081597X-20180104-01

10. Jhanji V, Ahmad S, Amescua G, et al. Corneal ectasia preferred practice pattern. Ophthalmology. 2024;131(4):P205-P246. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2023.12.038

11. Greenstein SA, Yu AS, Gelles JD, Huang S, Hersh PS. Long-term outcomes after corneal cross-linking for progressive keratoconus and corneal ectasia: a 10-year follow-up of the pivotal study. Eye Contact Lens. 2023;49(10):411-416. doi:10.1097/ICL.0000000000001018

12. Korb DR, Finnemore VM, Herman JP. Apical changes and scarring in keratoconus as related to contact lens fitting techniques. J Am Optom Assoc. 1982;53(3):199-205.

13. Bergmansson JP, Walker MK, Johnson LA. Assessing scleral contact lens satisfaction in a keratoconus population. Optom Vis Sci. 2016;93(8):855-860. doi:10.1097/OPX.0000000000000882

14. Cortina MS, Greiner MA, Kuo AN, et al. Safety and efficacy of epithelium-off corneal collagen cross-linking for the treatment of corneal ectasia: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2024;131(10):1234-1242. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2024.05.006

15. Deshmukh RS, Das AV, Vaddavalli PK. Evolving trends in the diagnosis and management of keratoconus over 3 decades. Cornea. Published online July 16, 2024. doi:10.1097/ICO.0000000000003635

16. Nath S, Shen C, Koziarz A, et al. Transepithelial versus epithelium-off corneal collagen cross-linking for corneal ectasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2021;128(8):1150-1160. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.12.023

17. Caporossi A, Mazzotta C, Paradiso AL, Baiocchi S, Marigliani D, Caporossi T. Transepithelial corneal collagen crosslinking for progressive keratoconus: 24-month clinical results. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2013;39(8):1157-1163. doi:10.1016/j.jcrs.2013.03.026

Articles in this issue

11 months ago

Education should be current, relevant, useful11 months ago

How do GLP-1 receptor agonists affect ocular health?Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.