Diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging—in practice

As efforts continue across the globe, optometrists need to take action in clinics.

Art by William Feriend

Diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging (DEIB): This has been a common and now familiar word group that has pierced the fabric of many academic and corporate institutions. Many of these organizations have hired DEIB strategists and consultants, created mission statements, hired people from diverse backgrounds, and promised to create a work environment that will allow folks to thrive. These words and this work are not new. Some original advocates of the Civil Rights era call this current time period a reawakening to social and racial injustice. Social unrest combined with a global pandemic highlighted health care’s role in the pursuit of equity and justice. COVID-19 revealed the disparity in access and outcomes across populations, particularly in those most vulnerable (poor, limited education, incarcerated, aged 65+ years, and specific racial and ethnic groups).

Within the realm of eye care, students rose up and demanded that their curricula include information about how to provide culturally competent care and inquired why their student body, educators, researchers, and administrators did not represent the broader population. Additionally, Black Eyecare Perspective—an organization cofounded by Adam Ramsey, OD, and Darryl Glover, OD—challenged all facets of the optometric industry, from our academic centers to the companies that produce the glasses and contacts we prescribe to our millions of patients, to commit to the 13% promise, thus publicly declaring to increase the representation of Black people in the industry to more closely align with their representation in the US population. Slowly but surely, the transformative work of DEIB has begun within the optometric profession. So what should that look like within a private practice setting?

First, let us consider how to define DEIB. Essentially, DEIB is the representation of groups of people from different backgrounds and lifestyles who are treated fairly and respected, have proportional access to opportunities and resources, and can contribute fully to an organization’s success because their emotional desire to be an accepted member of the group has been fulfilled. If that is an environment that is created, then all parties (staff, doctors, and patients) can expect to fully benefit from an inclusive practice.

The benefits of an inclusive work environment include the following:

» expands innovation, creativity, and productivity;

» leads to knowledge sharing and more resources at work;

» improves problem-solving;

» increases employee engagement and performance;

» results in better decision-making;

» increases accountability and transparency; and

» improves an organization’s reputations.

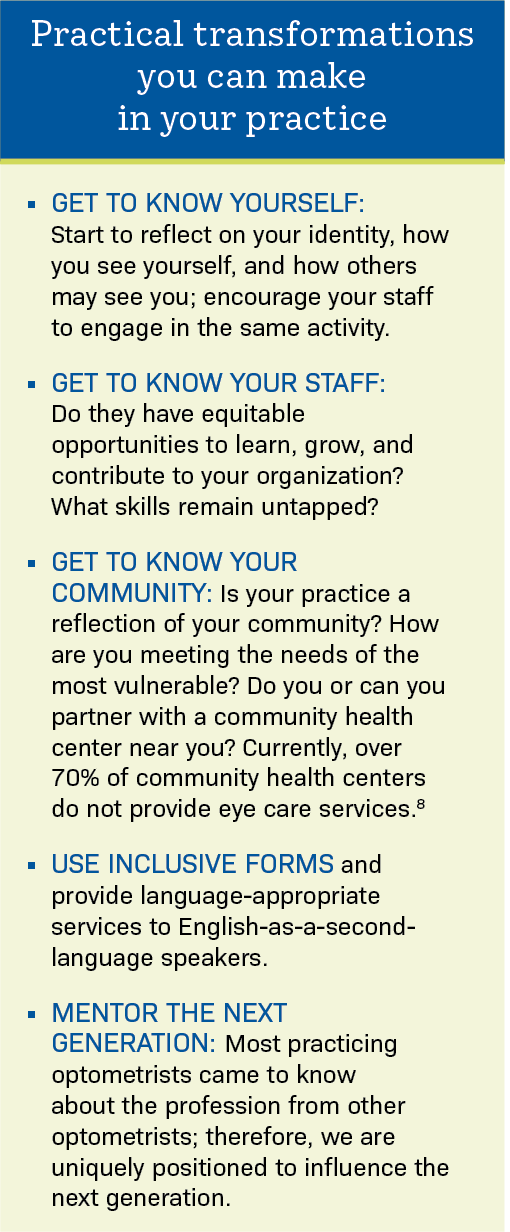

Steps needed to create an inclusive work environment are varied and can occur in no particular sequence. However, the following considerations should be made for your and your practice’s journey.

Bias awareness

Biases are the attitudes or prejudice in favor of or against one thing, person, or group compared with another, usually in a way considered unfair. There are generally 2 categories of bias1: explicit and implicit.

In explicit, or conscious, bias, a person is very clear about their feelings and attitudes and related behaviors are conducted with intent. Conscious bias, in its extreme, is characterized by overt negative behavior that can be expressed through physical and verbal harassment or through more subtle means such as exclusion.

Implicit, or unconscious, bias operates outside a person’s awareness and can be in direct contradiction to a person’s espoused beliefs and values. What is so dangerous about implicit bias is that it seeps into a person’s affect or behavior and is outside the full awareness of that person.

Bias is the basis of discrimination,2 stereotypes, microaggressions (with macro impact), and the consortium of “isms” (racism, sexism, classism) and phobias (homophobia, xenophobia). Combatting implicit3 bias begins with acknowledgment and awareness. We all have biases and act on them. Cultivating self-awareness begins with first understanding yourself: How do you identify yourself? What do you think are the most important parts of your identity? How do you think other people view you? How do other people treat you based on how they view you?

Next, we want to identify and name biases and assumptions we have about specific groups of people by reflecting on messages we have received from family members, friends, educators, the media, etc, that have impacted our beliefs about people. To mitigate bias as clinicians, we want to conceptualize implicit bias as a “habit of mind” to facilitate intentional behavioral change, challenge automaticity (slow down, see each patient as an individual), and challenge stereotypes and associations we have created over the years through individuation and stereotype replacement (would you treat that person the same way if they were a different gender, race, ethnicity, etc?).4 Once that understanding is cemented, then we can begin the work of understanding the way we view other people—how do you identify them and how do you treat them based on how you identify them?

Communication

As providers, we may presume that our experience and reputation precede us and that is what creates a great patient-provider relationship. However, patients’ top priorities are good communication and interpersonal manner.5 They expect their provider to make a personal connection, listen to and address their concerns empathetically, and communicate honestly about diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment options in clear language. Services (both written and oral) must be provided in a patient’s preferred language. To do otherwise would be in violation of the federal Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services standards.6 At a minimum, these standards require the availability of interpreters and translated documents.

Representation

We have heard the phrase “representation matters” and it continues to be used frequently and urgently in both public and private circles because it really does matter. Seeing oneself adequately represented inside and outside the exam room has proven to be critical to improving health care outcomes. Academically referred to as physician-patient concordance, the relationship between a doctor and their patient has emerged as an important dimension that may be linked to health care disparities or, inversely, health equity.7 Conceptually, concordance can be defined as a having similar or shared identity based on a demographic attribute, such as race, ethnicity, gender identity, or language.7 While it is atypical for a patient and their doctor to have many shared attributes, the cultural gap can be bridged by having this representation within your staff, or what I’ve coined as practice-patient concordance. Your staff should adequately reflect the community that you serve, most importantly, culturally, linguistically, racially, and ethnically.

Representation can also be demonstrated through the use of intake forms that use gender-inclusive language (ie, parent/guardian and nonbinary pronouns), diverse advertisements, and a diverse frame selection that will fit a variety of faces.

We must find purpose in and commit to the transformation that diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging can have in our practices. As the late, great Octavia Butler wrote, “Purpose unifies us: It focuses our dreams, guides our plans, strengthens our efforts.”

References

1. UCLA Office of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion YouTube page. Implicit bias lesson 4: explicit v. implicit bias. Accessed November 7, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5S7Je6kbGDY&t=1s

2. UCLA Office of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion YouTube page. Implicit bias lesson 2: attitudes and stereotypes. Accessed November 7, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7FgqGAXvLB8&t=1s

3. TED YouTube page. Verna Myers: how to overcome our biases? Walk boldly toward them. Accessed November 7, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uYyvbgINZkQ&t=2s

4. UCLA Office of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion YouTube page. Implicit bias lesson 6: countermeasures. Accessed November 7, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RIOGenWu_iA&t=4s

5. Elam AR, Lee PP. High-risk populations for vision loss and eye care underutilization: a review of the literature and ideas for moving forward. Surv Ophthalmol. 2013;58(4): 348-358. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2012.07.005

6. National culturally and linguistically appropriate services standards. US Department of Health & Human Services. https://thinkculturalhealth.hhs.gov/clas/standards

7. Street RL, O’Malley KJ, Cooper LA, Haidet P. Understanding concordance in patient-physician relationships: personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(3):198-205. doi:10.1370/afm.821

8. Shin P, Finnegan B. Assessing the need for on-site eye care professionals in community health centers. Policy Brief George Wash Univ Cent Health Serv Res Policy. 2009;1-23. Accessed November 7, 2022. https://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1021&context=sphhs_policy_briefs

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.