Dry eyes: A price to pay for clear skin?

When oral acne treatments lead to ocular surface disease, the solution lies in office-based therapies.

Acne takes several common forms that can affect individuals of virtually any age. Approximately 9.4% of the global population has acne.1 In teenagers and pregnant women, hormone changes are the underlying cause. Rosacea, which affects approximately 5% of the global population,2 causes redness and papule breakouts, most commonly in patients 30 years and older.

And since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals of all ages have developed mask acne—or “maskne”—as protective face masks change the skin’s microbiome, triggering breakouts and exacerbating underlying acne or rosacea.3

As someone who had acne as a teenager, I’m happy there are now many therapies available to help patients achieve clearer skin. However, as a medical optometrist, I see the effects of acne treatments on the meibomian glands and the ocular surface. After all, acne medications need to reduce oil and dry up blemishes—2 goals at odds with the production of healthy, functioning tear film.

Here, I’ll share the complications seen from prescription treatments and over-the-counter (OTC) products, and how today’s in-office procedures are helping my patients have clear skin and comfortable eyes.

Isotretinoin effects

Isotretinoin medications— such as Accutane (Roche), Absorica (Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd), Claravis (Barr Laboratories), Myorisan (Akorn), Zenatane (Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories)— are oral retinoids prescribed on-label for severe nodular acne and off-

label for a plethora of skin problems, including rosacea.4

It works by shrinking the sebaceous glands, which significantly lowers production of oils in the skin and reduces acne. Unfortunately, because the meibomian glands are sebaceous, oil-producing glands, this systemic medication shrinks them as well.

My patients who are taking isotretinoin or have used it in the past present with typical signs and symptoms of meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD): intolerable evaporative dry eye, keratitis, low tear breakup time (TBUT), fluctuating vision, grittiness, foreign body sensation, styes, and contact lens discomfort. Meibography shows that the glands of these patients have been clogged or atrophied. When I express their glands, the meibum is often thick, toothpaste-like and opaque. In my experience, the longer the patient has used isotretinoin, the more likely it is that some glands are lost.

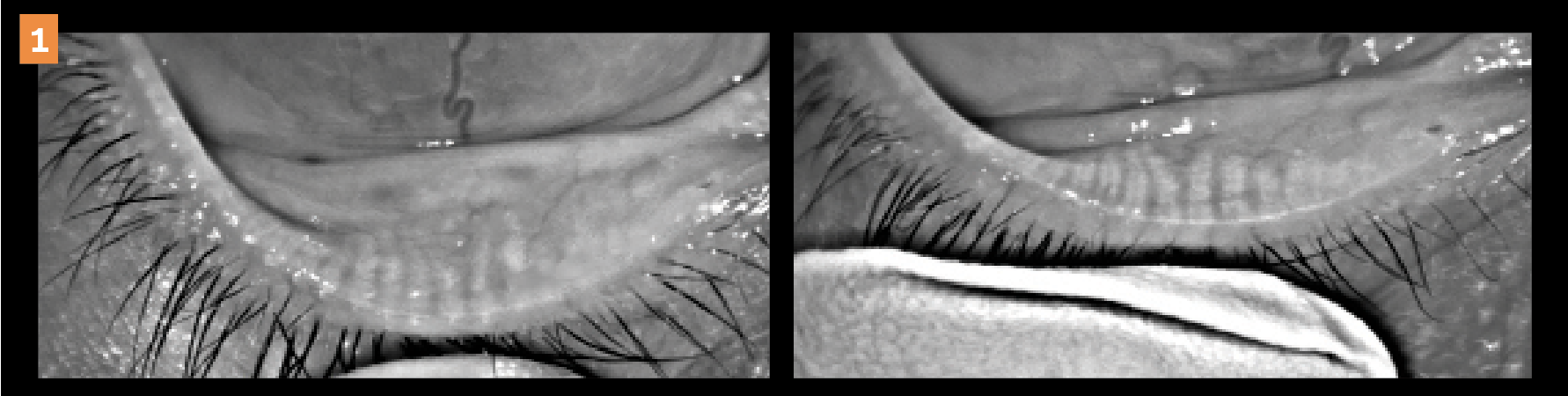

Figure 1: Meibography images show before (left) and after (right) in-office dry eye treatments of a 27-year-old female patient with a recent history of isotretinoin.

Figure 1 shows meibography images of a 27-year-old female patient with dry eye

disease (DED) before and after receiving in-office dry eye treatments.

A thorough history asking about medications is important, as our practice often sees patients of all ages that were prescribed isotretinoin (due to various skin problems). Some patients took isotretinoin years ago as teenagers, and it left a lasting impact on the meibomian glands. Even our older dry eye patients report increased frequency and severity of ocular symptoms after being prescribed isotretinoin for maskne or for post-pregnancy acne.

Likewise, patients are more likely to develop dry eye as they age, so isotretinoin raises the already high risk of MGD in older patients.

Topical medications and skin care products

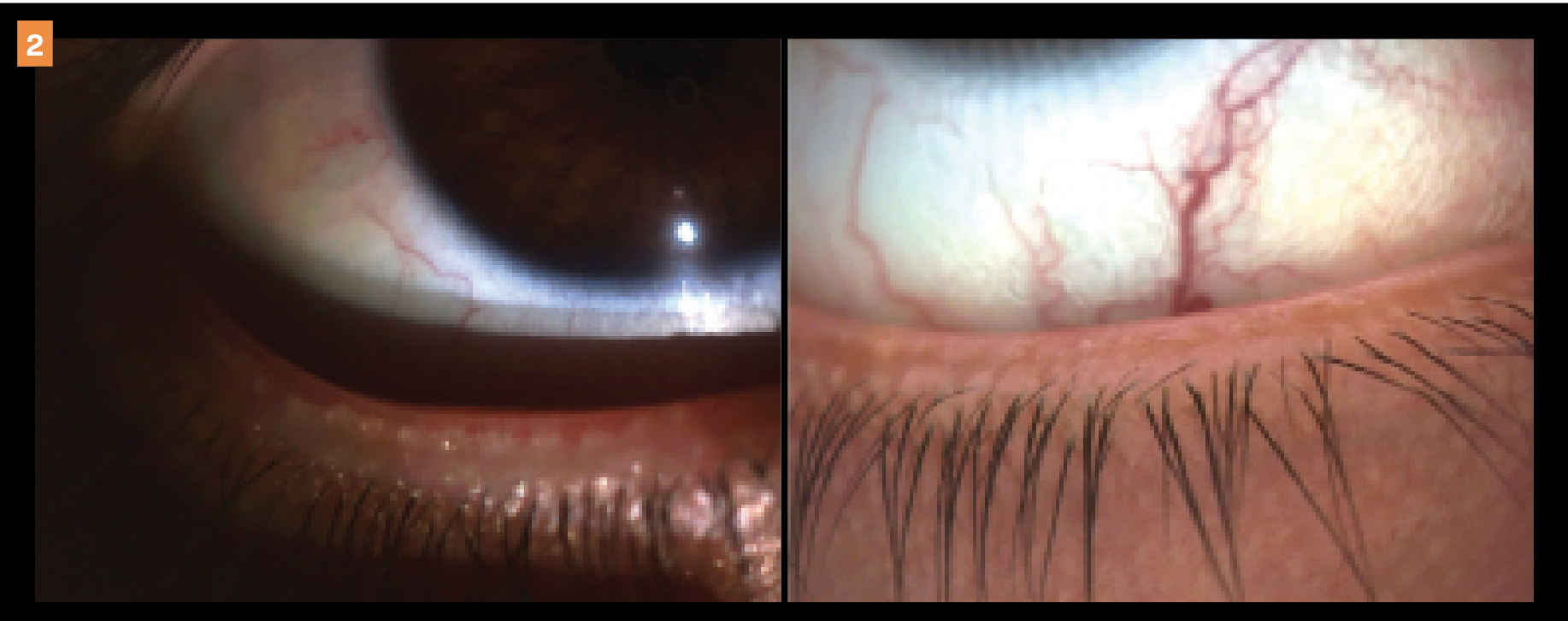

Although topical acne medications are applied directly to the skin, they must be used with care to avoid contributing to DED (Figure 2).

Patients should not use such topical medications near the eyes or when handling contact lenses.

Figure 2. Patient with a recent history of taking oral isotretinoin, which led to dry eye disease and meibomian gland dysfunction. Images show before (left) and after (right) in-office treatments, where the lid margin integrity and meibum function can be seen improving after office-based treatments.

Unfortunately, I also see patients with dry, irritated eyes who have been less careful with medications or other skin care products.

Tretinoin (Retin-A Cream, Janssen Pharmaceuticals) is a common prescription acne medication that tightens the skin. However, if it comes in contact with the eyelids and is absorbed, it can damage epithelial cells in the meibomian glands5 and cause significant dry eye symptoms. Common ingredients in OTC acne products—such as benzoyl peroxide and salicylic acid—can have similar effects.6

Synergistic treatments

While we can’t cure dry eye or MGD, we can reduce flare-ups and major episodes as well as provide patients more comfort by reducing the impact of the condition on our patients' quality of lives and daily activities.

We accomplish this by addressing the key contributing factors and the root cause of dry eye with office-based therapies—rather than relying solely on pharmaceuticals—because the goal is to remove or minimize patients’ treatment burden.

For patients who have used isotretinoin, I have the added goal of preserving the anatomical structure of the meibomian glands, as well as regenerating damaged glands, if possible. Three in-office therapies help in meeting these goals: eyelid exfoliation, thermal expression, and light-based therapy.

These work synergistically as a combined 3-step plan, or they may also be used independently, depending on a patient’s specific needs or presentation.

Step 1: Eyelid exfoliation

The BlephEx (Alcon) device and Zocular Eyelid System Treatment (ZEST) system are 2 ways to deep clean and remove eyelid scurf, plaque, bacterial biofilm, and demodex mites from the base of the eyelashes and at the opening of the meibomian glands.

For those patients with significant signs or symptoms of blepharitis, consider repeating 1 of these therapies 2 to 4 times a year.

Step 2: Advanced thermal expression

Immediately after eyelid exfoliation, I perform advanced thermal expression with LipiFlow (Johnson & Johnson Vision), Systane iLux (Alcon), or TearCare (Sight Sciences). This step warms and melts the meibum so it can be easily expressed from the clogged glands.

Removing the blocked unhealthy oils helps restore healthy tear quality, consistency, and stability. This can be repeated every 6 to 12 months, or patients can have it done sooner if their glands are prone to clogging.

Step 3: Light-based therapy

I perform OptiLight (Lumenis) light-based therapy during the same visit as thermal expression, and then continue every 2 to 4 weeks for a total of 4 sessions. OptiLight is the first and only light-based therapy that is FDA approved for dry eye management. It restores the function of the meibomian glands, improves TBUT, and breaks the cycle of inflammation that characterizes DED.

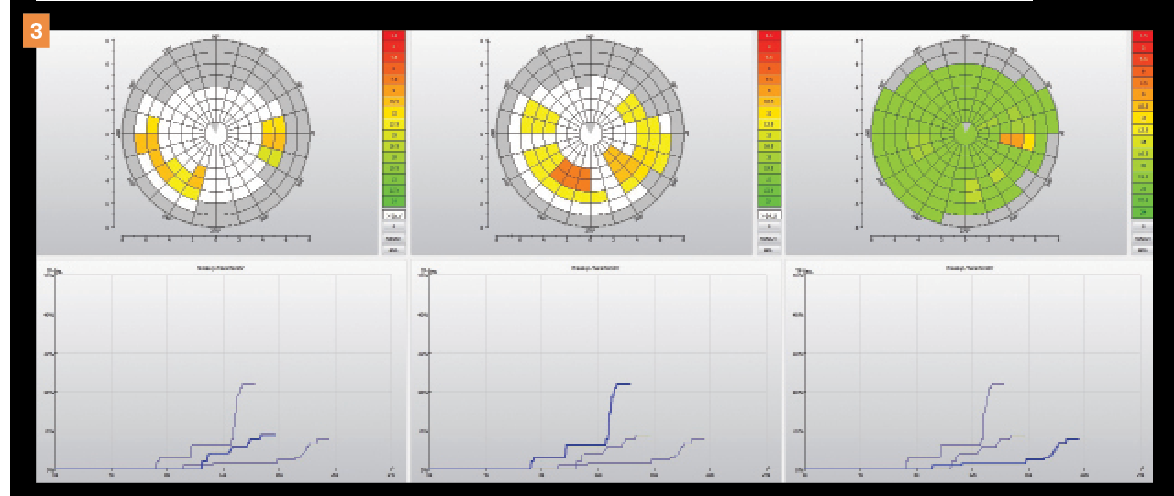

Figure 3 depicts noninvasive TBUT progress of a patient with DED over different visits (post-treatment), where significant improvement can be seen.

Figure 3. Progression of noninvasive tear breakup time over different visits reveals significant improvement. Pretreatment (left and middle) and after treatment (right) images are shown. Yellow, orange, and red on the graph indicate areas of tear instability. Green shows areas of normal tear stability. (All images courtesy of Kambiz Silani, OD.)

In patients who have impaired gland function from isotretinoin use, I have seen modest regeneration starting approximately 6 months after treatment, which is remarkable. It’s a relief to have this therapy for isotretinoin patients—without it, the meibomian gland damage is much more difficult to overcome, and patients would be less likely to see improvement.

After the initial 4 sessions, patients often ask to continue OptiLight maintenance

sessions because they appreciate the effects. My patients with milder cases do well with 3- to 6-month OptiLight maintenance, whereas patients with moderate to severe DED often need more frequent treatments.

After these treatments, I customize a home routine for patients to follow, which often complements and prolongs the benefits of the in-office treatments.

A typical dry eye kit may include a reesterified triglyceride omega-3 supplement; a warm compress; a high-quality preservative-free, lipid-based artificial tear; and a lid hygiene product (Avenova, NovaBay Pharmaceuticals).

(As an optional approach, there are even some at-home devices now available for patients to use safely and effectively, including NuLids and iTear neuro-stimulation.)

In addition to evolving both our in-office and at-home protocols, I also share tips regarding cleaner cosmetics, proper contact lens wear, optimal visual ergonomics, healthier diet, moderate exercise, and other lifestyle habits.

Switching skin treatments

It’s important to note that I never tell patients to stop using prescription medications such as isotretinoin. But I do educate them about how the medication is affecting their meibomian glands and may be contributing to their dry eye symptoms. I offer to connect with their dermatologist and discuss alternatives.

For example, I recently had a case where the patient had stopped driving because of fluctuating, blurry vision from MGD related to isotretinoin use. I discussed the problem with her prescribing physician, and the patient was happy to change skin treatments.

Alternatively, some patients enjoy how their skin looks when they take isotretinoin. Even though they experience discomfort in the eyes, these patients prioritize the aesthetic benefits. If they choose to continue with isotretinoin, I still offer to manage their dry eye symptoms. (Thankfully, isotretinoin is not a lifetime medication; patients are usually prescribed a 6-month course of the drug.)

To cut down on pharmaceuticals that contribute to dry eye, dermatologists may offer in-office procedures for acne and rosacea, including chemical peels or microdermabrasion. Moreover, photobiomodulation can help—in fact, OptiLight has an intense pulsed light handpiece that allows physicians to target the telangiectasia and reduce rosacea inflammation.

DED is such a multifactorial disease that even when optometrists identify major contributors such as acne medication, we have to check for other factors as well.

I’ve had patients with isotretinoin-driven MGD who spend long hours working on computers, wear face masks, overwear their contact lenses, and take common drying pharmaceuticals such as birth control pills, antihistamines, or antidepressants. I educate patients about all these factors and recommend behavioral and lifestyle changes when possible.

But for patients with acne, it’s important to let them know that they can get clear skin and still have comfortable eyes.

REFERENCES

1. Tan JKL, Bhate K. A global perspective on the epidemiology of acne. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172(suppl 1):3-12. doi:10.1111/bjd.13462

2. Gether L, Overgaard LK, Egeberg A, Thyssen JP. Incidence and prevalence of rosacea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179(2):282-289. doi:10.1111/bjd.16481

3. Damiani G, Gironi LC, Grada A, et al. COVID-19 related masks increase severity of both acne (maskne) and rosacea (mask rosacea): multi-center, real-life, telemedical, and observational prospective study. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(2):e14848. doi:10.1111/dth.14848

4. Nickle SB, Nathan Peterson N, Peterson M. Updated physician’s guide to the off-label uses of oral isotretinoin. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7(4): 22-34.

5. Periman LM, O’Dell LE. When beauty doesn’t blink. Ophthalmology Management. August 1, 2016. Accessed July 20, 2022. https://www.ophthalmologymanagement.com/issues/2016/august-2016/when-beauty-doesn-8217;t-blink

6. O’Dell LE, Sullivan AG, Periman LM. If I could turn back time. Advanced Ocular Care. November/December 2016. Accessed July 20, 2022. https://www.dryeyediva.com/_files/ugd/0f73d1_d63272a18a3e4921948cfe31a901c866.pdf

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.