- Vol. 10 No. 07

- Volume 10

- Issue 7

GPC leads to contact lens instability

Giant papillary conjunctivitis is a mechanical irritation, and it can masquerade as other conditions. This case illustrates how contact lens instability leads to a diagnosis of GPC.

A 29-year-old female presented for new glasses with a secondary complaint of recent intermittent blur at all distances with and without contact lenses. She reported that her contact lenses have been excessively moving and that her vision seems best immediately after blinking.

Although there had been no changes in the type or modality of contact lens worn successfully for over a decade, her best corrected visual acuity fluctuated at 20/25 in both eyes with minimal improvement after removing her monthly contact lenses and instilling artificial tears.

Upon slit lamp examination, noted in both eyes were corneal chaffing and inflammation superiorly, bilateral bulbar conjunctival injection, and moderate superficial punctate keratitis.

Additionally, there were numerous large papillae along the tarsal conjunctiva of the lower lids. Confirmed with lid eversion, it was clear that this patient was suffering from giant papillary conjunctivitis (GPC).

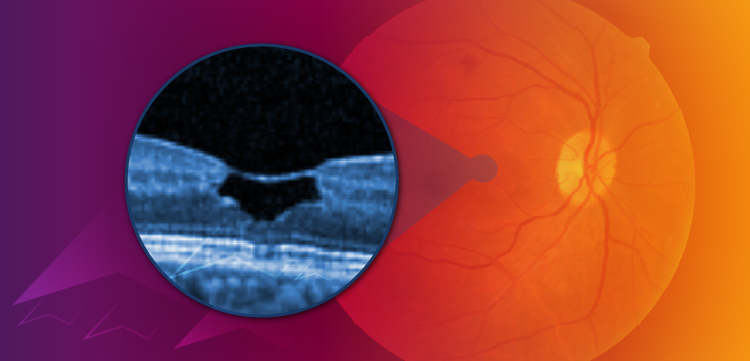

Corneal staining showed superficial punctate keratitis in both eyes at the first visit, which was more evident on the initial baseline tangential topography map. (See Figure 1.)

Treatment

At the initial exam, this patient was prescribed a combination of Lotemax (loteprednol etabonate 0.5%, Bausch + Lomb) for an immediate response and Bepreve (bepotastine besilate 1.5%, Bausch + Lomb) for a more long-term treatment.

At the follow-up visit two weeks later, the patient claimed minimal change in comfort; however, corneal topography exhibited slight improvement (Figure 1).

Once the patient fully committed to following the treatment regimen as directed and discontinued contact lens wear for several months, each subsequent visit showed improvement in corneal topography stability. With most long-time contact lens patients suffering from GPC, the hardest part of their advised regimen is to discontinue contact lens usage. As seen in the topographical scans, the ocular surface seems to improve each time the patient returned, enhancing most when she completely discontinued contact lens wear.

Despite successfully wearing monthly lenses for more than 15 years, the patient was switched to a daily disposable lens after six months of consistently not wearing contact lenses. Since making the switch to a daily lens, the patient has had no problems with contact lens instability related to GPC.

Discussion

The initial corneal insult that begins GPC’s inflammatory cascade usually starts with an ill-fitting contact lens edge or deposits on the lens that have mechanically irritated the conjunctival surface. However, GPC can also be caused by exposed sutures, blebs, extruding scleral buckles, elevated corneal scars, and even ocular prosthetics.1

As this case illustrates, the mechanical irritation from the lens edge irritated the patient’s steeper-than-average corneas that led to chronic corneal inflammation.

Unfortunately, GPC can be difficult to diagnose because patients with the condition can simultaneously exhibit other forms of allergy. Regardless, when a patient mentions chronic contact lens instability, it is an opportunity to dive deeper and re-evaluate contact lens modality and/or recommend discontinued use of contact lenses for a period.

GPC often occurs as a response to chronic, mechanical trauma that causes mast cells to be hyperactive and promote other immune cells to form small conjunctival papillae that coalesce into larger papillae.2

Often known as contact lens-induced papillary conjunctivitis, GPC has been associated with all types of contact lenses materials, including rigid, hydrogel, and silicone hydrogel.3

Complaints of excessive tearing, foreign body sensation, hyperemia, and contact lens instability are common signs and symptoms associated with GPC.

Unlike other allergy diagnoses, such as vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) and atopic keratoconjunctivitis (AKC), GPC is not an allergic reaction, and the patient complaint of itching is generally absent.1 By understanding that GPC is an inflammatory condition caused by repeated mechanical irritation, optometrists can better identify and treat these patients.

It is important for optometrists to discuss with patients that spectacle correction may offer a much-needed break from contact lens wear. As evidence shows, patients wearing a monthly contact lens had an increased rate of GPC, but switching to a more frequent contact lens replacement schedule decreased the incidence from 36 percent to 4.5 percent.4

Topography shows detail

Using topography to help identify and monitor ocular surface disease, optometrists can assess the cornea on a more detailed level to obtain a better understanding of the affected corneal areas.

Although both axial and tangential maps provide good data, tangential maps show more detailed information while axial maps display the average corneal changes.5

Often, a baseline topography scan reveals the missing puzzle piece to the final diagnosis. After all, GPC is estimated to affect 1 to 5 percent of the 12 million wearers of soft contact lenses in the United States and perhaps 1 percent of the 8 million wearers of rigid contact lenses.6

GPC masquerade

Technology can be useful to help diagnose corneal disease, but it is imperative to recognize that GPC can be masquerading as an allergic reaction, conjunctivitis, or as a pseudo-ectasia when assessed with a topographer. Furthermore, understanding that the underlying culprit of diagnosis and treatment of GPC is chronic inflammation secondary to mechanical trauma instead of an allergic process can help optometrists to be more efficient and accurate when managing the primary etiology.

References:

1. Chin T. GPC: Don’t call it an allergic reaction. Rev Optom. 2006;143(11). Available at: https://www.reviewofoptometry.com/article/gpc-dont-call-it-an-allergic-reaction. Accessed 6/7/18.

2. Greiner JV, Abelson MB, ed. Giant Papillary Conjunctivitis In: Allergic Disease of the Eye. New York: WB Saunders; 2001:140-60.

3. Porazinski AD, Donshik PC. Giant Papillary Conjunctivitis in Frequent Replacement Contact Lens Wearers: A Retrospective Study. CLAO J. 1999 Jul;25(3):142-147.

4. Donshik PC, Porazinski AD. Giant Papillary Conjunctivitis in Frequent Replacement Contact Lens Wearers: A Retrospective Study. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1999;97:205-220.

5. Anderson D, Kojima R. Topography: A Clinical Pearl. Optom Manag. 2007;42(2):35. Available at: https://www.optometricmanagement.com/issues/2007/february-2007/topography-a-clinical-pearl. Accessed 6/7/18.

6. Allansmith M. National Research Council (US) Working Group on Contact Lens Use Under Adverse Conditions; Ebert Flattau P, editor. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1991. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK234094/. Accessed 6/12/18

Articles in this issue

over 7 years ago

Eyelid taping may offer temporary alternative to blepharoplastyover 7 years ago

Resveratrol may be key in AMD stroke patient treatmentsover 7 years ago

Peroxide lens care effective for GP lens wearersover 7 years ago

Use MIGS prior to late-stage glaucomaover 7 years ago

Why documenting target IOP helps ODsover 7 years ago

Demand for optometry projected to growover 7 years ago

4 tips to help staff identify contact lens candidatesalmost 8 years ago

3 tips to upgrading astigmatic contact lens patientsNewsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.

.png)