- April digital edition 2023

- Volume 15

- Issue 04

The complicated ins and outs of pediatric glaucoma

Pediatric glaucoma, although rare, can cause irreversible vision loss and leave children visually impaired if not treated timely and adequately.

As a new parent, I now understand why parents constantly worry about their children. Will they be happy and healthy? Will they have any developmental delays? What if they fall and hurt themselves? What if they are bullied? The possibilities are endless, but as an eye care provider I also worry about conditions that could cause vision loss.

Pediatric glaucoma is one of these conditions that, although rare, can cause irreversible vision loss and leave children visually impaired if not treated timely and adequately. Primary congenital glaucoma accounts for 50% to 70% of all pediatric glaucoma, and its prevalence is approximately 1 in 10,000 births.1 Other types of pediatric glaucoma can be acquired (eg, through trauma, intraocular surgery) or secondary to a systemic condition, such as Sturge-Weber syndrome, or ocular anomaly, such as aniridia.

As optometrists we don’t often treat patients with pediatric glaucoma, but we identify the signs and symptoms and place the appropriate referral when necessary. This could be during a routine eye exam, InfantSEE exam or referral from a local pediatrician with concerns. Therefore, being knowledgeable and competent with the signs and symptoms of pediatric glaucoma, specifically primary congenital glaucoma, is very important.

According to the American Academy of Ophthalmology, only 25% of primary congenital glaucoma is present at birth, but it can develop anytime during the first year of life.2 Common symptoms that parents may notice are epiphora, blepharospasm, and photophobia, but these can be missed or confused with other conditions such as a nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Some signs to look for when examining infants with suspected primary congenital glaucoma are clouding of the cornea (corneal edema) secondary to elevated IOP. It often accompanies breaks in the Descemet membrane known as Haab striae. This elevation in the IOP also causes enlargement of the cornea in 1 or both eyes. In an infant younger than 12 months, a corneal diameter of greater than 12 mm is considered enlarged.3

Comprehensive care

A complete ophthalmic exam of a patient who may have glaucoma should include IOP, funduscopic exam, and cycloplegic refraction. The clinician also should initially assess the infant’s general appearance and visual behavior. Are they visually engaged? Are they exploring the room? Are they mobile? Do their eyes appear normal and clear or are they cloudy in appearance? Do both eyes look in the same direction? Is there any presence of nystagmus?

After completing a thorough history and observing the patient’s interactions, visual assessment should be completed. This can include whether each eye fixes and follows a toy or object. It should be checked whether a newborn blinks to light response. Teller cards or LEA Grating paddles could be used for quantitative visual acuity.

The examination of the cornea is crucial to determine the clarity, size, and any abnormalities of the anterior segment, which can be completed with the parent holding the infant with their face in a handheld slit lamp, or with an external 20D lens with external light source if the child will cooperate (Figure 1).

IOP assessment can be difficult to obtain but is vital to the exam. IOP can be completed via iCare, Goldmann applanation tonometry (the gold standard), or Tono-Pen. Central corneal thickness with pachymetry can supply more information but adjusting IOP secondary to pachymetry is not recommended because of other factors affecting corneal thickness (corneal scarring, corneal edema, etc). A funduscopic exam with the binocular indirect ophthalmoscope allows evaluation of the optic nerve for a progressive increase in cupping or asymmetric cup to disc ration of 0.2 microns or more secondary to elevated IOP.3 Along with optic nerve changes from an elevated IOP, there can be an associated elongation of the eyeball. This could result in an associated large myopic shift or progressive high myopia associated with primary congenital glaucoma highlighting why a cycloplegic dilation is essential.4

If it is determined that an infant has 2 or more of the above signs of glaucoma, then an urgent referral to a pediatric ophthalmologist is crucial with the diagnosis of primary congenital glaucoma. Unfortunately, medication management of primary congenital glaucoma does not show sustained efficacy as primary treatment and these patients often require surgical management, which is why the pediatric ophthalmologist needs to be involved quickly. Glaucoma medication, either topical or oral, can be used for temporary treatment prior to surgery to aid in clearing corneal edema for better ocular examination and surgical intervention. After surgical intervention, topical treatment may be implemented as an adjunctive therapy for aided control of IOP.

Medication management

When considering starting infants on topical or oral medication for eye pressure, there are some systemic considerations that could be lethal if not prescribed correctly. Adverse reactions can also present atypically in children, and because they are not able to communicate symptoms and parents may not readily recognize them, close monitoring is important.

β-blockers such as timolol can provide a 20% to 25% IOP reduction. It is typically prescribed at 0.1% or 0.25% in smaller children because of the risk of bronchospasms and bradycardia. β-blockers should be avoided in patients with reactive airways. When unable to avoid, selective betaxolol should be considered in patients with asthma. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors offer a 25% reduction with topical medication and 40% reduction in IOP with oral medication. The topical form is systemically safer and better tolerated but not as effective. When prescribing carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, it is important to avoid in patients with compromised corneas and sulfa drug allergies.

Metabolic acidosis, poor feeding, and minimal to no weight gain are systemic concerns with oral acetazolamide (Diamox) and even possible with topical treatment in newborns so it should be avoided when possible. α-Agonists such as brimonidine can cause a 2 to 6 mmHg reduction in IOP but should be avoided in small children and infants because of potential central nervous system suppression. In infants and children less than 40 lb, it can cause bradycardia, hypotension, hypothermia, hypotonia, and apnea. Apnea has an even higher incidence if paired with a β-blocker such as timolol. Therefore, brimonidine should be avoided in all small children because of the potentially fatal adverse events of the medication.

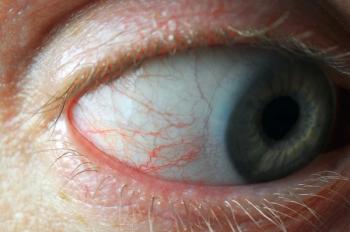

Prostaglandins can provide a 25% to 30% reduction in IOP and has minimal adverse events. Prostaglandins can result in increased eyelash growth and/or eye redness, so if only using it in 1 eye it may be worth mentioning to the parent. Prostaglandins should be avoided when inflammatory properties present, such as uveitic glaucoma (Figure 2).5,6

Combination drops are convenient for the patient and parent, especially when more than 1 medication is required to manage IOP, but they are considered off label for use in children. Because of the risk of adverse events, there are limited options for combinations drops; brimonidine is present in brimonidine 0.2%/timolol 0.5% (Combigan) and brinzolamide 1%/brimonidine 0.2% (Simbrinza).

Conclusion

It is the role of the primary eye care provider to diagnose these patients and urgently refer when necessary to reduce the potential amount of vision loss and optic nerve damage. Early detection can be key in preventing these patients from requiring low-vision services. Management of IOP reduction can be very tricky given risk of systemic adverse events and often requires surgical interventions. Effective communication with the ophthalmologist and building trust can aid in the primary eye care provider’s ability to treat these patients and better care for our pediatric patients.

References

1. Karmel M. Childhood glaucoma: the challenges inherent in treating a vulnerable population. EyeNet Magazine. 2016:45-49.

2. Okorie A, Madu A. Diagnosis and treatment of primary congenital glaucoma. American Academy of Ophthalmology. 2010. Accessed February 2023. https://www.aao.org/eyenet/article/diagnosis-treatment-of-primary-congenital-glaucoma

3. Bagheri N, Wajda B, Calvo C, Durrani A, eds. The Wills Eye Manual. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2016.

4. Mandal A, Chakrabarti D, Chakrabarti R. Primary congenital glaucoma—pathogenesis, clinical features, diagnosis, differential diagnosis and management. Diagnosis and Management of Glaucoma. 2013:442. doi:10.5005/jp/books/11801_40

5 Dorkowski M, Williamson J, Rixon A. A guide to applying IOP-lowering drugs. Review of Optometry. 2018;155(7):24.

6. Giaconi JAA, Coppens G, Zeyen T. Pediatric glaucoma: glaucoma medications and steroids. Pearls of Glaucoma Management. 2016:481-486. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-49042-6_51

Articles in this issue

over 2 years ago

Silicon Valley Bank failure: What physicians need to knowover 2 years ago

Increase your capture rate with tiered pricingover 2 years ago

Being a woman in optometryover 2 years ago

Amniotic membranes: Clinical use for anterior segment diseasealmost 3 years ago

Maintaining eye health in 4 simple stepsalmost 3 years ago

Q&A: How is the landscape of geographic atrophy changing?almost 3 years ago

A pregnancy sleep-OSA-dry eye triadNewsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.