Treating inflammation tackles filamentary keratitis

Corneal filaments frequently recur after removal, and resolution occurs only by treating the patient’s underlying inflammation. This case illustrates the need to move to atypical therapies, such as N-acetylcysteine.

Editor's note: This case report is the first in a series by members of Intrepid Eye Society.

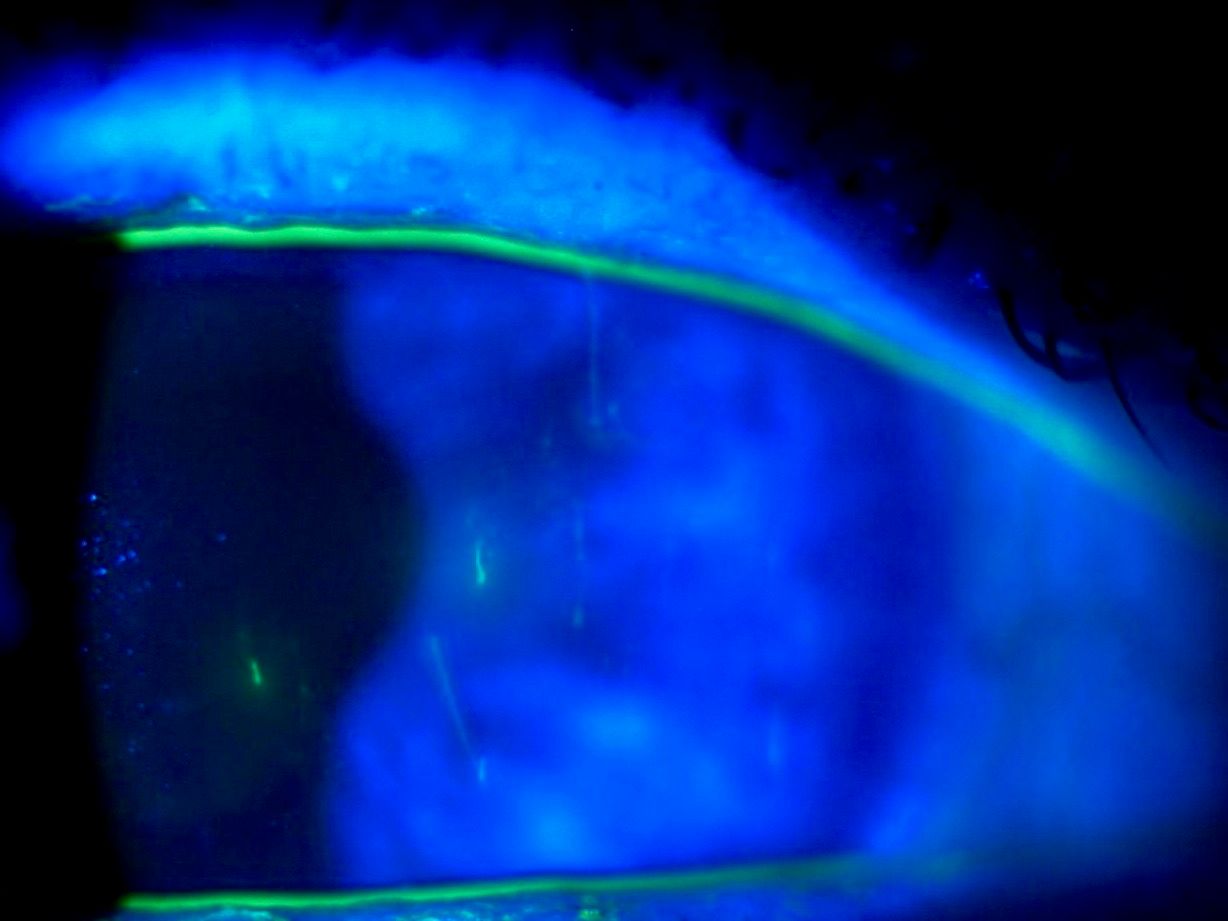

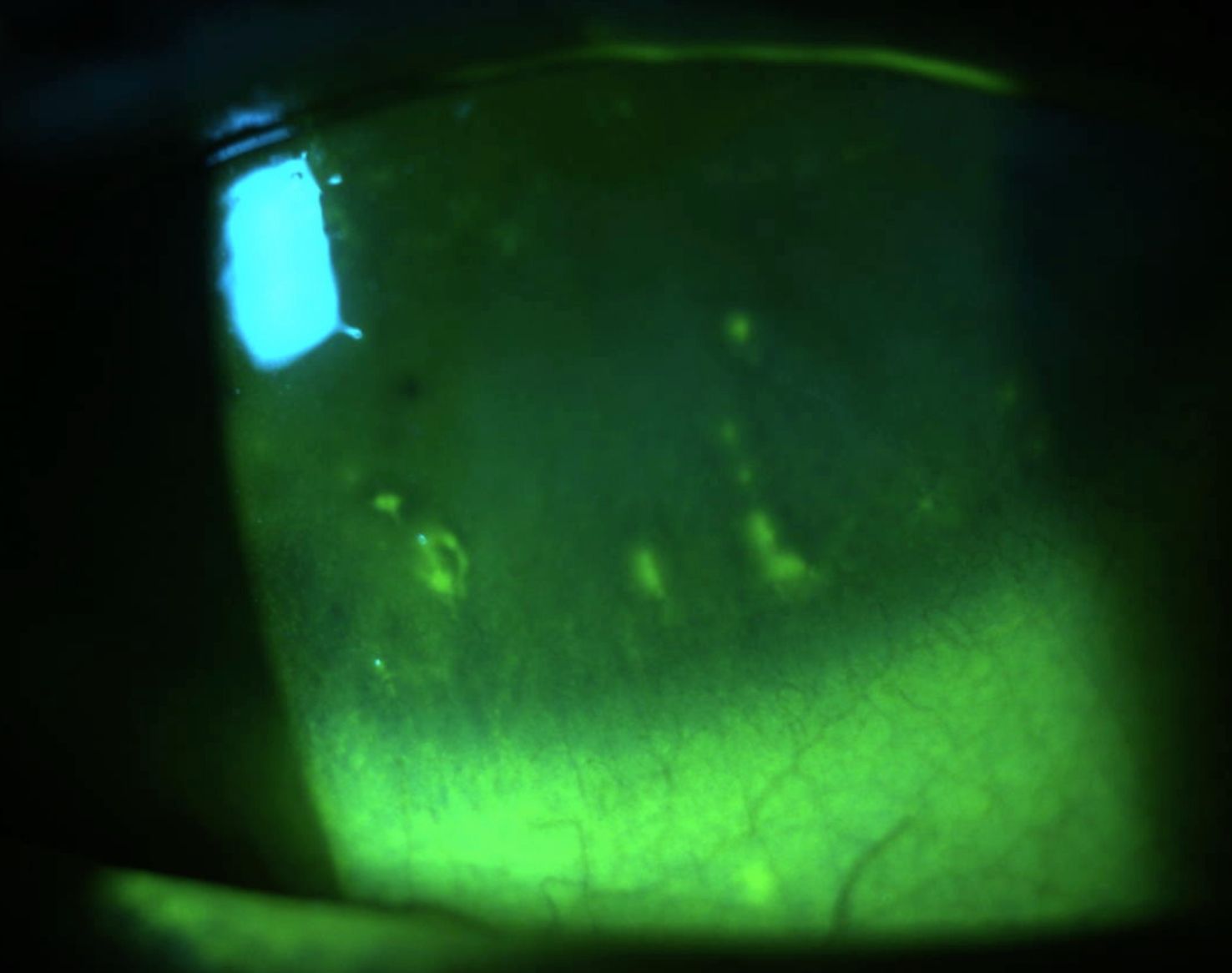

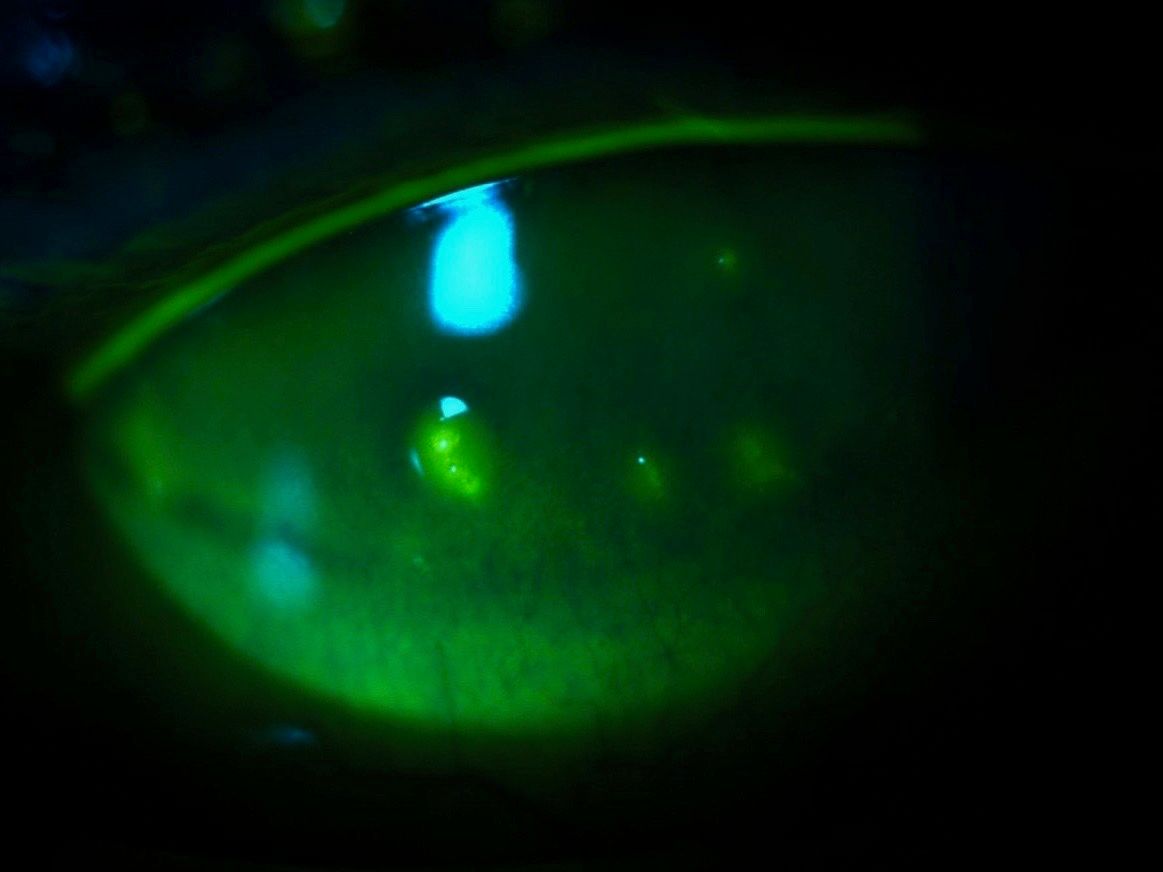

Fluorescein staining comes in many different patterns and presentations. Although corneal filaments tend to stand out when stained with fluorescein, they can be missed and mistaken for excessive tear debris, which is common in ocular surface disease.

Adherence of these mucus strands to the corneal basal epithelium or basement membrane can be a differentiating feature of filamentary keratitis that can help lead the clinician down the right path in the treatment and management of this condition.

Case

A 56-year-old female patient presented to our clinic for consultation. She was referred from an outside optometrist for severe dry eye disease. The patient presented with complaints of a sandy, gritty feeling in both eyes, especially at night and before bed. She also complained of fluctuating vision, worse in the morning and evening.

Her only medications were omega-3 supplements. The referring provider prescribed fluorometholone 0.1% (FML, Allergan) three times per day into her right eye; however, she reported no improvement in symptoms after using this medication for 10 days. Her medical history was unremarkable.

Related: New products, advancements in dry eye

Entering visual acuity was 20/40 OD and 20/20 OS with a recent spectacle correction. Entrance tests and intraocular pressure (IOP) were normal, as was her dilated fundus exam.

Anterior segment exam revealed mild meibomian gland disease (MGD) in both eyes, a minimal tear meniscus in both eyes, and 2+ injection in both eyes. A significant amount of superficial punctate keratitis in both eyes (3+ and 2+, OD and OS, respectively) was also noted. In addition, several small filaments were seen attached to the inferior cornea in the right eye.

After suspicion of an underlying systemic etiology, a rheumatology consult and a Sjögren’s lab panel was ordered in coordination with the patient’s primary-care physician. This patient’s tentative diagnosis of Sjögren’s syndrome and secondary dry eye was confirmed by rheumatology. The patient began systemic therapies, including oral pilocarpine (Salagen, Eisai) and hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil, Sanofi-Aventis).

Figure 1.

The patient was diagnosed with severe dry eye disease and filamentary keratitis. Initial treatment included removal of the filaments, aggressive lubrication, and prednisolone acetate 1% (Pred Forte, Allergan) steroid drops six times daily in both eyes.

Once the anti-inflammatory medications were on board and there was noted stabilization of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP9) levels with InflammaDry (Quidel) testing, we opted to perform complete punctal occlusion to maximize tear volume on the ocular surface.

As our patient’s condition improved with the initial therapy, the patient was changed to Lotemax (loteprednol etabonate, Bausch + Lomb) to minimize the side effect profile and Xiidra (lifitegrast, Shire) for long-term anti-inflammatory therapy.

Unfortunately, filaments recurred after several months of treatment. Consequently, filaments were again removed at their base, and 10% N-acetylcysteine (Mucomyst, Cumberland Pharma) was added three times daily.1 The patient continues to improve on this therapy.

Discussion

Filamentary keratitis is an unusual, atypical, and frankly confounding pathological manifestation. It can be associated with several ocular conditions and has systemic implications and associations, including Sjögren syndrome, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and cranial nerve palsies.4

Histologically, filaments are comprised of an epithelial cell core, surrounded by mucins and an array of various inflammatory cells and mediators.2,9 There is debate about the exact pathophysiology of filament formation. One theory points to changes in the mucus-to-aqueous ratio of the tear film leading to increased mucus production, thereby altering the polarity of the epithelial surface and adherence of strands to the epithelium.4

A different hypothesis points to mechanical damage to the corneal epithelium secondary to ocular surface or systemic diseases. The combination of friction and an irregular surface provides attachment sites for filaments. The breakdown of the intact basal epithelium and persistent mucus plaque further prevents healing and re-epithelialization.4

Corneal filaments stain well with rose bengal and lissamine green, and these additional dyes may help the clinician better locate and treat mild, early, or subtle filaments.2

The filaments can, and should be removed at the slit lamp with forceps; however, recurrence is common.2 If the base of the filament is not completely removed recurrence is highly likely.6

Related: Why meibography can be a game-changer in treating dry eye

Patients with corneal filaments experience long-term relief and resolution only by identifying and treating the underlying inflammation and insult to the ocular surface and corneal epithelium.

Ongoing therapies for these patients include on- and off-label usage of anti-inflammatory topical drugs such as corticosteroids, Xiidra, or Restasis (cyclosporin, Allergan).6 More obstinate cases may require atypical therapies such as autologous serum, N-acetylcysteine drops, or amniotic membrane.5-7 Other therapies include bandage contact lenses, including scleral contact lenses.3

Mucomyst or N-acetylcysteine is a mucolytic agent designed to help patients with respiratory issues and excessive mucus production. Conversely, a 2013 Cochrane review in cystic fibrosis found no benefit of this therapy.8 An unusual use of this medication is in the treatment of paracetamol (acetaminophen) overdose by enhancing the metabolism of acetaminophen by the liver.1 Interestingly, it is also being studied for its psychiatric effects in conditions such as autism, Alzheimer's disease, and traumatic brain injury.

Conclusion

When treating a patient with filamentary keratitis, control the inflammation completely with both short-term and long-term therapies. Include integrated care with other specialties such as rheumatology and primary care help to treat the whole patient, not just the ocular manifestations.

After the inflammation stabilizes, provide an adequate environment for the corneal epithelium to heal and restructure. This include maximizing tear film volume and reducing frictional forces and external stressors. Additional treatment options are advancing technologies such as amniotic membranes and prosthetic environments (such as scleral lenses). Therapeutic alternatives like autologous serum and mucolytic agents are also useful tools in these chronic and sometimes recalcitrant cases.

References

1. Acetadote Package Insert. Cumberland Pharmaceuticals. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2006/021539s004lbl.pdf. Accessed 4/20/18.

2. Bron AJ, de Paiva CS, Chauhan SK, Bonini S, Gabison EE, Jain S, Knop E, Markoulli M, Ogawa Y, Perez V, Uchino Y, Yokoi N, Zoukhri D, Sullivan DA. TFOS DEWS II pathophysiology report. Ocul Surf. 2017 Jul;15(3):438-510.

3. Boston Sight. BostonSight PROSE Treatment Information for Patients and Doctors. Available at:

http://www.bostonsight.org/Content/Files/public/BostonSight_PROSE_Information_for_Patients_and_Doctors_current.pdf. PDF. Accessed 4/20/18.

4. Mannis MJ, Holland EJ, Gensheimer WG, Davidson RS. Chapter 85: Filamentary Keratitis. In: Cornea: Fundamentals, Diagnosis and Management. Vol 1. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1025-1029.

5. Pachigolla G, Prasher P, Di Pascuale MA, McCulley JP, McHenry JG, Mootha VV. Evaluation of the role of ProKera in the management of ocular surface and orbital disorders. Eye Contact Lens. 2009 Jul;35(4):172-5.

6. Pentapati M, Shah S. Filamentary keratitis: A case series. Int J Scientific Res Pub. 2015 Mar;5(3):1-7.

7. Read SP, Rodriguez M, Dubovy S, Karp CL, Galor A. treatment of refractory filamentary keratitis with autologous serum tears. Eye Contact Lens. 2017 Sep;43(5):e16-e18.

8. Tam J, Nash EF, Ratjen F, Tullis E, Stephenson A. Nebulized and oral thiol derivatives for pulmonary disease in cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Jul 12;(7):CD007168.

9. Tanioka H, Yokoi N, Komuro A, Shimamoto T, Kawasaki S, Matsuda A, Kinoshita S. Investigation of the corneal filament in filamentary keratitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009 Aug;50(8):3696-702.

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.