- October digital edition 2021

- Volume 13

- Issue 10

Approach patients with low vision on an individual basis

Clinicians must think creatively for solutions to vocational rehabilitation

Low vision rehabilitation is a segment of optometry that lends itself to creativity in case management and approaches to help patients achieve their goals. As practitioners begin to establish a low vision practice, they will have the opportunity to provide value to their patients’ lives by developing solutions to achieve vocational, social, and daily living goals.

By the numbers

The low vision patient population is considered to be primarily a geriatric patient base with reading goals. Although older patients make up most of the population presenting for low vision services,1 many patients are still working or have other, varied goals. People with vision impairment are underemployed, and low vision practitioners can have a major impact on helping patients achieve sustainable, competitive employment.

According to research conducted by the American Foundation for the Blind, in 2017 there was a 37% labor force participation rate among people with vision impairment and a 12% unemployment rate. The general working population had a 73% labor force participation rate and a 5% unemployment rate during the same period.2 The estimated rate of employment for those with vision impairment is increasing over time, although it’s still low.

When approaching concerns related to employment and accommodations, it is critical to understand the Americans with Disabilities Act Amendments Act (ADAAA) of 2008. Key points from the ADAAA include3,4:

»Employers cannot ask about a vision impairment before making a job offer, but they can ask about the applicant’s ability to do certain tasks (ie, read labels).

»Job applicants do not need to disclose their vision impairment unless they need a reasonable accommodation for the job application (ie, large print).

»An employer can ask about an obvious impairment (ie, dog-guide user) if the employer believes that an accommodation will be necessary to reasonably perform the job.

»After making an offer, the employer can ask about the impairment and require a medical exam if all potential employees receive the same treatment.

»The employer can ask additional details once the impairment is disclosed but cannot withdraw the job offer based on the impairment (unless the applicant cannot meet a specific medical standard, such as in a police department).

People with vision impairments must understand their rights and consider legal counsel or support from the local state agency for the blind if they have specific questions as they go through a hiring process or a discussion about new accommodations needed in the workplace. Reasonable accommodations include a variety of visual and nonvisual aids, including video magnifiers, modified hours, transportation assistance, and accessible document formatting.

The low vision practitioner plays a key role in helping patients find the devices and tools to best serve them in a current job or for future employment. This plan is developed through a detailed low vision history, device assessment, and collaborative plan of care.

Step 1: Understand the problem with clinical history

Low vision rehabilitation serves an important role in improving functional visual ability and providing appropriate adaptations to make visually mediated tasks easier to complete.1,5,6 Additional research shows that early rehabilitation and intervention may be critical in patients of younger working age.7

An effective low vision evaluation comes with an understanding of the patient’s goals and the visual tasks they find difficult. The clinician also must understand the patient’s overall visual ability in the key functional domains of reading, mobility, driving, visual motor ability, glare tolerance, and visual recognition. These functional domains come from studies exploring visual difficulties of patients with low vision as measured by patient-reported outcomes and visual function questionnaires.8,9

Key questions to ask regarding employment include:

»What is the level of detail required? This can be used to estimate the level of magnification needed (to estimate required equivalent power or magnification).

»What is the working distance? Know at what distance the patient requires and if modification is possible.

»What are workplace restrictions on the types of devices that can be used?

»Are there multiple tasks and demands or a singular demand?

Step 2: Understand magnification requirements, low vision formulas

Many formulas are relevant to magnification determination; however, the most routinely used involve determination of the appropriate dioptric starting power for reading 1M standard print. Four methods determine the power required to read 1M print10-16:

»Kestenbaum’s rule uses the inverse of the distance acuity. It predicts that the dioptric power needed for a patient to read 1M print is the inverse of the best-corrected distance acuity of the better seeing eye—ie, a patient with 20/100 acuity should be able to read 1M print with a +5.00 D near add or a +5.00 D hand magnifier.

»The inverse-of-the-near-acuity method uses a similar approach to Kestenbaum’s rule except for using best-corrected near acuity rather than distance acuity. A patient who can read 2M print at 40 cm with their bifocals (ie, 0.40/2.0M acuity) would require a +5.00 D near add to read 1M print.

»The Acuity Reserve Rule states that most people read at a maximal rate when the print size is at least 2 times greater than their threshold print size. Thus, if fluent reading of print is the goal, the dioptric requirement should be at least doubled from that predicted by Kestenbaum’s or the Inverse of the Near Acuity rule.

»Inverse of the Critical Print Size Method arose from work finding considerable differences in print sizes at maximal reading rate and threshold when reading continuous text. Thus, many clinicians now use Legge’s MNRead Acuity Charts to assess a patient’s critical print size (ie, print size near maximal reading rate [MAR]) and threshold print size and use the former to predict dioptric requirements for reading 1M print. This method is commonly used in cases where patients may have high reading demands.

Reading print is a common goal for low vision patients,17 but it is not the only vocationally related task for which magnification may be required. The task may be less common. In such cases, because it may be more relevant to determine whether the patient can see the detail required at a close working distance, estimate magnification by considering one of the following:

For cases which require an infinite or intermediate working distance, a a near telescope may be suitable.

Step 3: Evaluate the device

Evaluating a device that a patient brings to the office visit or simulating the required task is optimal. Doing so allows the clinician to evaluate multiple approaches. However, further assessment may be needed at the workplace. In these instances, collaboration with a certified vision rehabilitation therapist (CVRT) or occupational therapist (OT) can be critical.

Tips to improve device success:

»When working to address task-specific goals, encourage the patient to bring the items required so the setup can be simulated.

»In many cases, the setup is too complex or cumbersome to simulate in the office. When this occurs, a referral to a low-vision therapist or OT is critical.

»The CVRT or OT can help accurately quantify the lighting as well as measurements needed for optical solutions.

»The CVRT or OT can bring a trial frame, telescope, or other tools that are recommended to evaluate in the task-specific environment.

This collaboration is essential to gathering specific feedback from the patient in their environment as well as feedback from a trained professional on the patient’s additional needs. The CVRT or OT may recommend changing the working distance, adding a device with contrast sensitivity enhancement, shifting to a hands-free device, or making other adjustments to the device recommendation. To facilitate this process, the low vision provider must fully communicate the optical design of the device and request specific feedback to finalize the device and augment the clinical decision-making process.

Conclusion

In summary, understanding the patient’s concerns, difficulties, and the task at hand is key to prescribing appropriate visual assistive equipment. Collaborating with occupational therapists, rehabilitation therapists, and other professionals can facilitate the development of the best plan for patients.

References

1. Goldstein JE, Massof RW, Deremeik JT, et al; Low Vision Research Network Study Group. Baseline traits of low vision patients served by private outpatient clinical centers in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(8):1028-1037. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2012.1197

2. Key employment statistics for people who are blind or visually impaired. American Foundation for the Blind. Accessed April 27, 2020.

3. Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. S. 933. Congress.gov. July 26, 1990. Accessed September 30, 2021. https://www.congress.gov/bill/101st-congress/senate-bill/933?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22%22%5D%7D&s=8&r=107

4. The Americans with Disabilities Act Amendments Act of 2008. US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Accessed February 14, 2021.

5. Goldstein JE, Jackson ML, Fox SM, Deremeik JT, Massof RW; Low Vision Research Network Study Group. Clinically meaningful rehabilitation outcomes of low vision patients served by outpatient clinical centers. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133(7):762-769. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.0693

6. Stelmack J. Quality of life of low-vision patients and outcomes of low-vision rehabilitation. Optom Vis Sci. 2001;78(5):335-342. doi:10.1097/00006324-200105000-00017

7. Macnaughton J, Latham K, Vianya-Estopa M. Rehabilitation needs and activity limitations of adults with a visual impairment entering a low vision rehabilitation service in England. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2019;39(2):113-126. doi:10.1111/opo.12606

8. Massof RW, Ahmadian L, Grover LL, et al. The activity inventory: an adaptive visual function questionnaire. Optom Vis Sci. 2007;84(8):763-774. doi:10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181339efd

9. Stelmack JA, Szlyk JP, Stelmack TR, et al. Measuring outcomes of vision rehabilitation with the Veterans Affairs low vision visual functioning questionnaire. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(8):3253-3261. doi:10.1167/Iovs.05-1319.

10. Kestenbaum A. Reading glasses for patients with very poor vision. Am J Ophthalmol. 1953;36(8):1143-1144.

11. Whittaker SG, Lovie-Kitchin J. Visual requirements for reading. Optom Vis Sci. 1993;70(1):54-65. doi:10.1097/00006324-199301000-00010

12. Lovie-Kitchin JE, Oliver NJ, Bruce A, Leighton MS, Leigiaton WK. The effect of print size on reading rate for adults and children. Clin Exp Optom. 1994;77(1):2-7. doi:

13. Raasch TW, Rubin GS. Reading with low vision. J Am Optom Assoc. 1993;64(1):15-18.

14. Legge GE, Ross JA, Isenberg LM, LaMay JM. Psychophysics of reading. clinical predictors of low-vision reading speed. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992;33(3):677-687.

15. Legge GE, Ross JA, Luebker A, LaMay JM. Psychophysics of Reading. VIII. the Minnesota Low-Vision Reading Test. Optom Vis Sci. 1989;66(12):843-853. doi:10.1097/00006324-198912000-00008

16. Legge GE, Rubin GS, Pelli DG, Schleske MM. Psychophysics of reading--II. low vision. Vision Res. 1985;25(2):253-266. doi:10.1016/0042-6989(85)90118-x

17. Brown JC, Goldstein JE, Chan TL, Massof R, Ramulu P; Low Vision Research Network Study Group. Characterizing functional complaints in patients seeking outpatient low vision services in the United States. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(8):1655-1662.e1. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.02.030

Articles in this issue

over 4 years ago

The future of physician waiting roomsover 4 years ago

How to drop a vision plan and replace revenueover 4 years ago

Beyond anxiety in patients with glaucomaover 4 years ago

Top 9 sports vision resourcesover 4 years ago

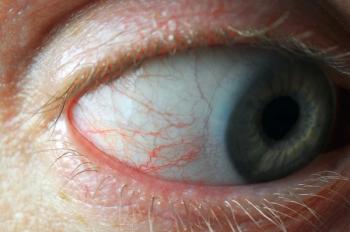

Demodex: Recognize it and treat itover 4 years ago

Central serous retinopathy is not a benign diseaseover 4 years ago

Use OCT to determine scleral lens clearanceover 4 years ago

Delta COVID-19 variant forcing meeting changesNewsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.