- September digital edition 2024

- Volume 16

- Issue 09

Autism and poor eye tracking: Theories and recommendations for optometrists

Abnormalities in the amygdala causing eye contact avoidance, and dorsal visual stream dysfunction remain some of the theories regarding autism and poor eye tracking.

In humans, strong eye contact is vital for social interactions and communication with others.1 Findings from studies indicate that taking in information from others’ eye regions is critical for facial processing, such as identification of others’ identity, expression, and intention.1 Not making eye contact during social interactions is a common diagnostic criterion for autism spectrum disorder (ASD).2 This may result in individuals with ASD struggling to extract information from individuals during face-to-face interactions.1-4 It is possible that low social skills seen in children with ASD may be caused by the lack of visual cues when they avoid eye contact.3 However, it remains unknown whether the lack of reciprocal gaze is due to social reasons or an alteration in the visual and processing neural pathways in those with ASD.2 Multiple conflicting hypotheses exist for the mechanisms responsible for reduced eye contact in individuals with ASD.5 In this paper, we examine some of the popular neurophysiological theories for why individuals with ASD make less eye contact.

Relevance to optometry

Eye contact is crucial for human interaction, communication, and everyday life.1,6 When we walk and engage in various activities that make up natural human behavior, our saccades, pursuit eye movement, and the vestibulo-ocular reflex come into play.6 Good saccades and pursuit eye movements are necessary for humans to track moving targets.7,8

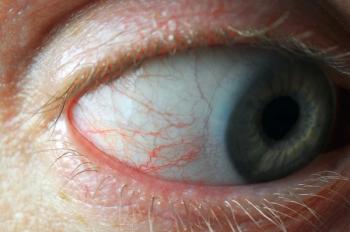

Children with ASD may have a dysfunction of the cortical network responsible for saccade triggering.9 Saccades and pursuits are controlled by the oculomotor system. Specifically, the cortical pathway for saccades and pursuit eye movement includes the frontal and supplementary eye fields. The frontal eye fields are connected to the caudate nucleus (Figure 1).9 The caudate nucleus tail is connected to the amygdala (Figure 2).10

Most people with poor reading fluency have oculomotor dysfunction. Findings from one study showed that training eye fixation could help this.11 Furthermore, in her lecture at the Autism Tree Global Annual Neurodiversity Conference in La Jolla, California, Karen Pierce, PhD, stated that eye tracking can be used to diagnose and treat individuals with ASD, even from a young age.12 This is because eye tracking can check for duration, frequency, and direction of eye contact and gaze movements.13

Current theories

Amygdala theory of autism

Brothers proposed that the amygdala is part of an area in the brain that is heavily involved in social interaction and called it the “social brain.”14 Because individuals with ASD have impaired social skills, Baron-Cohen et al investigated whether autism is caused by amygdala abnormalities.15-17 The researchers investigated multiple types of evidence, such as similarities between individuals with ASD and patients with amygdala lesions as well as structural and functional neuroimaging of the amygdala in participants with ASD.16 The majority of their findings led them to develop the amygdala theory of autism, which states that abnormalities in the amygdala, specifically decreased volume and reduced activity, are found in those with ASD.17

Furthermore, the amygdala theory of autism was applied specifically to poor eye contact skills of patients with ASD.5 Researchers state that poor eye contact is a direct result of hypoactivity of the amygdala.5 It is hypothesized that decreased activity in the amygdala leads to the conversation partner’s eyes being marked as less salient. This causes the individual with ASD to look at another visual cue that is deemed more important. Therefore, individuals are not purposefully avoiding eye contact; rather, their amygdala is not receiving enough stimulation to mark others’ eyes as an important visual target during social interactions.5

Eye avoidance hypothesis

On the other hand, the eye avoidance hypothesis suggests a causal relationship that is the opposite of the amygdala theory of autism.5 Dalton et al were some of the first researchers to specifically investigate eye contact in correlation to brain activity in ASD using photographs and were the first to provide evidence for the eye avoidance hypothesis.18 Previous research showed that the fusiform gyrus is typically highly activated during facial processing tasks in individuals who are neurotypical; however, it is hypoactivated during these tests in individuals with ASD.18 For a long time, it was thought that the fusiform gyrus receives input from the amygdala, but it has since has been proved to have bidirectional communication with the amygdala.18,19 Therefore, Dalton et al investigated the relationship between the fusiform gyrus and amygdala activity and time spent fixating on eyes in participants with ASD.18 They found that activation of both the fusiform gyrus and the amygdala had a strong and positive correlation to the amount of time spent focusing on the eye region in the group with ASD. Compared with the control group, individuals with ASD experienced hyperactivation of the amygdala when gazing at the eye region of the photographs. Based on these findings, Dalton et al formulated what was soon to be known as the eye avoidance hypothesis.18

The eye avoidance hypothesis states that poor eye contact in individuals with ASD is a direct result of hyperactivity of the amygdala.5 Eye contact causes the amygdala to be overstimulated, resulting in the individual being uncomfortable and their brain wanting to look away from the eye region.5 The hypoactivation of the fusiform gyrus in patients with ASD is then a direct result of the reduced eye contact.18

Dorsal visual stream dysfunction hypothesis

In a recent study by Hirsch et al, neuroimaging, pupillometry data, and eye tracking were done using functional near-infrared spectroscopy during 2-person and video eye contact interactions for both participants who are neurotypical and participants with neurodivergence.4 All participants were instructed to make direct eye contact with either their in-person laboratory partner or the person on the video for 3-second periods. Compared with individuals who are neurotypical, those with ASD had lower right dorsal-parietal activity and greater right ventral temporal-parietal activity when making eye contact in person.4

This observation is consistent with the dorsal visual stream dysfunction (DVSD) hypothesis, which has been used to suggest causation for impairments in visually guided motion, processing of motion, saccades, and eye tracking in individuals with ASD.20-22 The neural circuitry of visual processing splits into 2 separate visual streams after the primary visual cortex: the dorsal visual stream and the ventral visual stream.20 The dorsal visual stream, a pathway originating in the primary visual cortex in the occipital lobes that extends to the posterior parietal lobes, is vital for visually guided movement and provides a spatial map within the mind. In contrast, the ventral visual stream projects from the primary visual cortex to the temporal lobe and is vital for face and object recognition (Figure 3). Therefore, the DVSD hypothesis states that autism is caused by abnormalities and hypoactivation in the dorsal visual pathway, which results in many of the common symptoms such as impairments in eye movements and fine motor skill movements that require heavy visual input.20 The research done by Hirsch et al supports the DVSD hypothesis and even suggests that the hypoactivation of the dorsal stream in the brains of those with ASD is met with hyperactivation of the ventral stream to compensate for the loss of visual processing in the other stream.4

Recommendations for the optometrist

Given that the frontal eye fields are connected to the caudate nucleus, which is involved in the control of saccades and pursuits, and the caudate nucleus lies close to the amygdala, the causation of poor eye contact in ASD may be connected to the circuit controlling eye movement.9,10 We recommend optometrists test eye tracking in every child. Findings from studies show that the average age for diagnosis of autism is between the age of 3 to 5 years. To decrease this average age of diagnosis, every child should be tested for eye tracking by the age of 18 months.13 All children should have an eye examination as early as possible, and the following should be done for eye tracking:

- Case history or family history of autism

- Binocular examination: extraocular motility testing, pursuit and saccades, near point of convergence

- Cycloplegic refraction

We hope that with artificial intelligence, we obtain a form of objective testing for eye tracking in infants and toddlers.

Conclusion

This is not an exhaustive list of the theories in the literature. We recommend optometrists and parents keep an eye on new research on this topic.

The fact remains that children with ASD may have poor eye contact, and this may affect reading and sports. The brain’s neuroplasticity means we can continue to offer sports and vision therapy to help with central and peripheral awareness of these patients. If children younger than 3 years are discovered to have poor eye tracking, would offering some form of vision therapy earlier to aid eye tracking be helpful? Vision therapy is helpful in patients with special needs.23 What if we provided treatment for poor eye tracking before children were diagnosed by the age of 3 years? Perhaps that would increase their reading, sports, and central/peripheral awareness skills.

References:

Hessels RS, Benjamins JS, Niehorster DC, et al. Eye contact avoidance in crowds: a large wearable eye-tracking study. Atten Percept Psychophys. 2022;84(8):2623-2640. doi:10.3758/s13414-022-02541-z

Freeth M, Foulsham T, Kingstone A. What affects social attention? social presence, eye contact and autistic traits. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e53286. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0053286

Winczura B. Deficiencies of eye contact and face-to-face interactions in social relations among children with autism. Pedagogika. 2014;116(4):226-239. doi:10.15823/p.2014.060

Hirsch J, Zhang X, Noah JA, et al. Neural correlates of eye contact and social function in autism spectrum disorder. PLoS One. 2022;17(11):e0265798. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0265798

Stuart N, Whitehouse A, Palermo R, Bothe E, Badcock N. Eye gaze in autism spectrum disorder: a review of neural evidence for the eye avoidance hypothesis. J Autism Dev Disord. 2023;53(5):1884-1905. doi:10.1007/s10803-022-05443-z

Foulsham T. Eye movements and their functions in everyday tasks. Eye (Lond). 2015;29(2):196-199. doi:10.1038/eye.2014.275

Orban De Xivry JJ, Lefèvre P. Saccades and pursuit: two outcomes of a single sensorimotor process. J Physiol. 2007;584(1):11-23. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2007.139881

Erkelens CJ. Coordination of smooth pursuit and saccades. Vision Res. 2006;46(1-2):163-170. doi:10.1016/j.visres.2005.06.027

Caldani S, Steg S, Lefebvre A, et al. Oculomotor behavior in children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism. 2020;24(3):670-679. doi:10.1177/1362361319882861

Friedman JH, Chou KL. Mood, emotion, and thought. In: Goetz C, ed. Textbook of Clinical Neurology. Elsevier; 2007:35-54.

Nazir M, Nabeel T. Effects of training of eye fixation skills on the reading fluency of children with oculomotor dysfunction. Pak J Educ. 2019;36(1):61-80. doi:10.30971/pje.v36i1.1158

Pierce K. Eye-tracking: the future of diagnostics, prognostics, and treatment planning in autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Presented at: Autism Tree Global Neurodiversity Conference; December 1, 2023; La Jolla, CA. Accessed July 23, 2024. https://www.uctv.tv/shows/Eye-Tracking-The-Future-of-Diagnostics-Prognostics-and-Treatment-Planning-in-Autism-Spectrum-Disorder-ASD-with-Karen-Pierce-Autism-Tree-Project-Foundation-Global-Neurodiversity-Conference-2023-39170

Asmetha Jeyarani R, Senthilkumar R. Eye tracking biomarkers for autism spectrum disorder detection using machine learning and deep learning techniques: review. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2023;108:102228. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2023.102228

Brothers L. The social brain: a project for integrating primate behavior and neurophysiology in a new domain. Concepts Neurosci. 1990;1:27-51.

Price JL. Comparative aspects of amygdala connectivity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;985:50-58. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07070.x

Herrington JD, Taylor JM, Grupe DW, Curby KM, Schultz RT. Bidirectional communication between amygdala and fusiform gyrus during facial recognition. Neuroimage. 2011;56(4):2348-2355. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.03.072

Baron-Cohen S, Ring HA, Bullmore ET, Wheelwright S, Ashwin C, Williams SC. The amygdala theory of autism. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24(3):355-364. doi:10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00011-7

Dalton KM, Nacewicz BM, Johnstone T, et al. Gaze fixation and the neural circuitry of face processing in autism. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(4):519-526. doi:10.1038/nn1421

Trevisan DA, Roberts N, Lin C, Birmingham E. How do adults and teens with self-declared autism spectrum disorder experience eye contact? a qualitative analysis of first-hand accounts. PLoS One. 2017;12(11):e0188446. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0188446

Hay I, Dutton GN, Biggar S, Ibrahim H, Assheton D. Exploratory study of dorsal visual stream dysfunction in autism; a case series. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2020;69:101456. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2019.101456

Freud E, Behrmann M, Snow JC. What does dorsal cortex contribute to perception? Open Mind (Camb). 2020;4:40-56. doi:10.1162/opmi_a_00033

Why people with autism have trouble making eye contact. Psychiatrist.com. November 14, 2022. Accessed March 16, 2024. https://www.psychiatrist.com/news/why-people-with-autism-have-trouble-making-eye-contact

Taub MB, Bartuccio M, Maino DM. Visual Diagnosis and Care of the Patient With Special Needs. LWW; 2012.

Pouget P. The cortex is in overall control ‘voluntary’ eye movement. Eye. 2015;29:241-245. doi:10.1038/eye.2014.284

Thalamus & Diencephalon. Neuroanatomy.com. Accessed July 30, 2024.

https://neuroanatomy.ca/regions/thalamus.html# Chalup S. The regions of the brain that are active for faces. Researchgate.net. Accessed July 30, 2024. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/The-regions-of-the-brain-that-are-active-for-faces_fig1_270756859

Articles in this issue

over 1 year ago

Inside the overlap between scleral lenses and dry eyeover 1 year ago

Case report: Superior limbic keratoconjunctivitisover 1 year ago

Contemporary care in GA: Practice patterns are evolvingover 1 year ago

To treat or not to treat: Fixing the glitch in glaucomaNewsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.