Compounded medications in ophthalmic patient care

This far-less-understood option can fill multiple needs for a practice.

Most eye care professionals are aware that there are brand-name and generic drug options for surgical, glaucoma, and dry eye patients. But a third category, compounded pharmaceuticals, is less well understood.

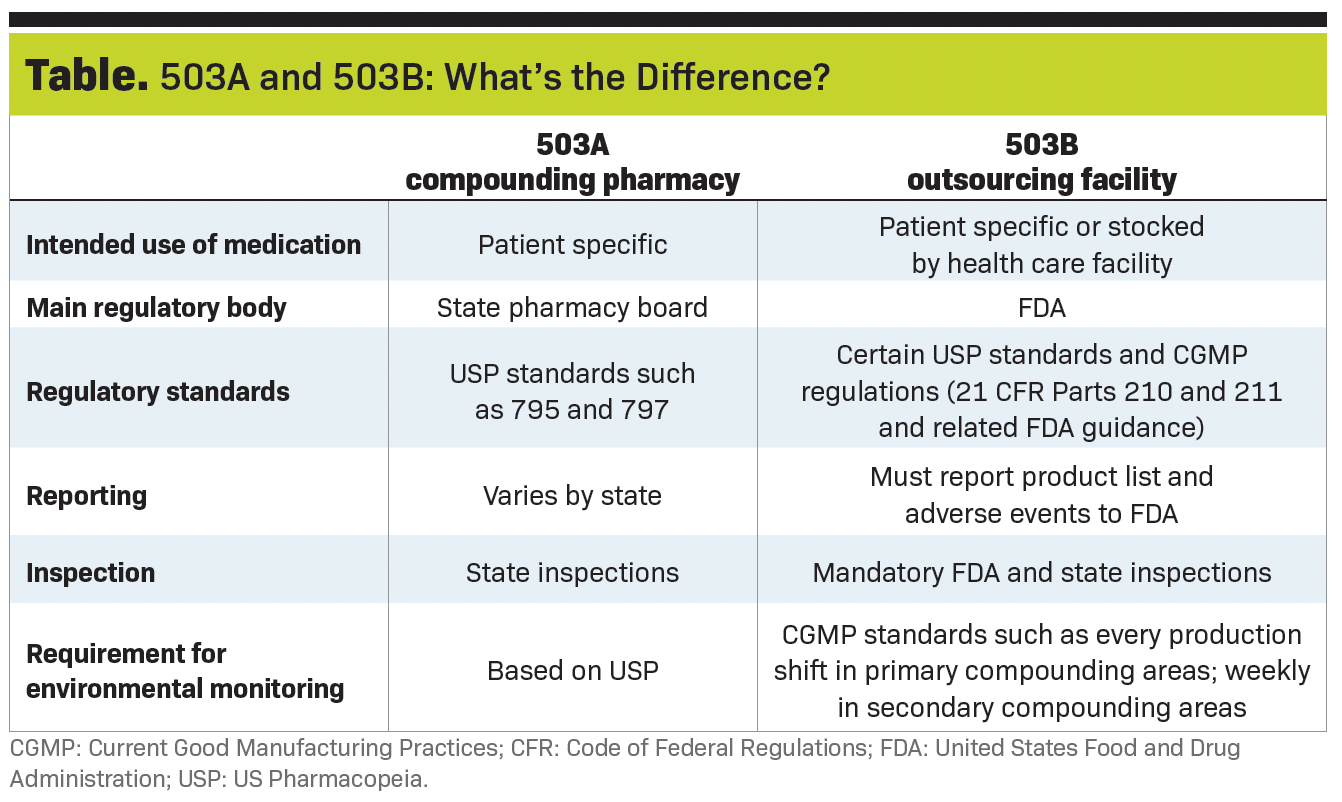

Compounded medications may be used for a variety of reasons. They may be ordered for a particular patient from an accredited 503A compounding pharmacy or stocked for regular use when obtained in bulk from a 503B outsourcing facility (see Table.)

503B facilities are subject to United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) inspection authority.

They must follow the same high manufacturing standards as commercial pharmaceutical companies so doctors can feel confident in the reliability and quality of their medications.

Compounded drugs are an important source for otherwise unavailable medications—and for improving adherence, convenience, and affordability for patients.

Addressing gaps

Compounding pharmacies fill an important gap by providing specialty therapeutics for unique situations. Patients with infectious ulcers are some of the most obvious beneficiaries.

For these patients, we often need to order fortified antibiotics or drops tailored to the to the antimicrobial susceptibility of a cultured pathogen.

Related: Shared care of the ocular surface before and after cataract surgery

Recently I treated a male patient with a culture-positive fungal infection. I started him on the only commercially available antifungal, natamycin, but he developed a significant allergic reaction, breaking out in hives.

I then ordered compounded amphotericin B, which cleared the ulcer. I have also sometimes ordered higher concentrations of cyclosporine or anti-inflammatory medications for patients who required aggressive treatment with minimal drop frequency.

Compounding pharmacies may also stock or custom-make preservative-free (PF) options of common medications for patients who have significant ocular surface disease or preservative-related adverse effects. There is no other commercial source for PF dorzolamide or brimonidine, for example.

Finally, I have relied on compounding pharmacies during temporary national shortages of cycloplegic agents and dorzolamide.

Perioperative care

In our surgical group practice, we have moved to compounded combination drops from a 503B FDA-registered outsourcing facility that we order in bulk for stock to provide to patients, either at cost or as part of the perioperative care package for procedures like LASIK.

Patients love having a simpler postoperative regimen and being able to skip a trip to the pharmacy after surgery.

Most of our cataract patients get an intracameral antibiotic / steroid / nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) injection at the conclusion of surgery. Intracameral antibiotics have been shown to reduce the risk of endophthalmitis 5-fold.1

Related: Shared care of the ocular surface before and after cataract surgery

Patients then go home with a compounded triple drop (Dex-Moxi-Ketor, ImprimisRx) that combines all 3 medications into a single drop instilled once daily.

This takes the number of daily drops needed after surgery from 9 to just 1 drop (assuming a traditional regimen of antibiotic 4 times a day, steroid 4 times a day, and NSAID drug once a day).

With this approach, we are confident that patients have received the right medications, with no substitutions or prescriptions going unfilled due to cost.

Needing only 1 drop per day is a huge help for older cataract patients who may have significant barriers to adherence, including lack of dexterity, forgetfulness or confusion, or requiring help from family or a friend to instill drops.

The greater the complexity of the regimen, the higher the probability these patients will miss doses of the medications needed to protect them from endophthalmitis, edema, nonresolving postoperative inflammation, and pain.

The compounded triple drop also often costs patients hundreds of dollars less than 3 separate name-brand medications, although this can vary depending on their insurance coverage.

It also saves the practice time and the effort required to deal with pharmacy call-backs, patient confusion over substituted generics, and prior authorizations.

Related: A narrative guide for cataract postoperative surgical care

Of course, optometrists aren’t typically the ones selecting the postoperative medications. Nevertheless, I think it is important to talk to your surgical partners about what they are using postoperatively.

Some of the patient experience wins (or frustrations) with postoperative drops get reflected back on the referring optometrist by association.

Chronic topical therapy

Compounded drops may also be a good option for certain categories of patients who are on chronic therapy for dry eye or glaucoma, but who are also struggling with cost and compliance issues.

For my patients with glaucoma, I typically prescribe commercially available drops first. Many have a unique mechanism of action and some are available in low-cost generic form.

But if a patient who needs 3 or 4 different medication classes is struggling to afford or correctly instill them, I will consider a compounded multiagent drug in a single bottle.

Although the efficacy of compounded fixed-combination drugs hasn’t been formally evaluated by the FDA, I have found them to have similar efficacy as or be effective than all the medications taken separately.

Compounded cyclosporine (Klarity-C, ImprimisRx) can also be an option for patients who can’t afford other immunomodulators for dry eye.

In summary, compounded medications can fill multiple needs for a practice.

The biggest win for our practice has been using compounded multiagent drops to offer postoperative patients the chance to get the protection they need with a much less burdensome regimen.

Reference

1. Endophthalmitis Study Group, European Society of Cataract & Refractive Surgeons. Prophylaxis of postoperative endophthalmitis following cataract surgery: results of the ESCRS multicenter study and identification of risk factors. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33(6):978-988. doi:10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.02.032

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.