OCT-A evaluation uncovers significant retinal findings in leukemia patient

Case report details diagnosis based on imaging diagnostics.

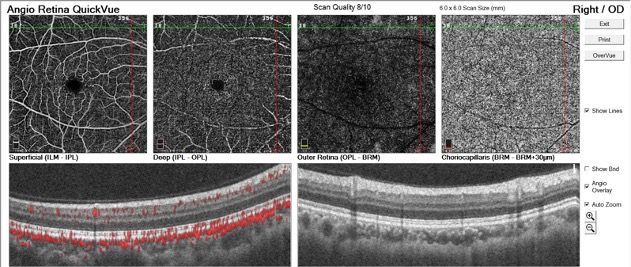

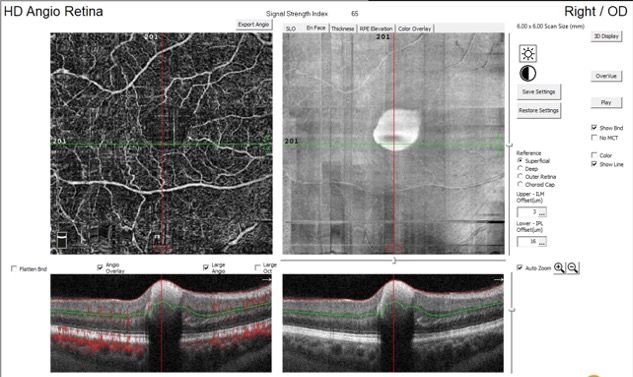

Figure 1. Normal OCT-angiograph. Top row, from left to right, the 4 panels show superficial and deep retinal capillaries, outer retinal circulation, and choriocapillaris. Note the borders of each segment. Middle row: OCT cross sections show corresponding retinal and choroidal circulation in the left panel.

A 42-year-old man was referred for consultation after being discharged from the hospital for leukemia treatment. The patient’s main complaint was central “blur” involving the right eye, which he first noticed after a round of chemotherapy. He did not require a refractive correction and was taking no other medications.

Visual acuity in the right eye was 20/200 with eccentric viewing. The patient complained of a dark spot in his central field of view on occlusion of the uninvolved left eye, and pinhole testing was not effective in improving his vision.

To understand the significance of OCT-A findings, it is important to recognize its data-gathering potential. Fluorescein angiography evaluates the integrity of the retinal circulatory systems, whereas OCT-A captures the motion of red blood cells within capillaries.

Envision a time-lapse photograph of a street at night with cars traveling along it. The photograph captures motion as the white and red lines of the headlights and taillights.

Similarly, motion capture of red-blood cells within intact capillaries is reflected in the OCT-angiograph as opposed to the output of a fluorescein angiography study documenting integrity of the circulatory systems of the eye, an angiogram.

Figure 1 (at top) shows a normal angiograph from a 30-year-old patient.

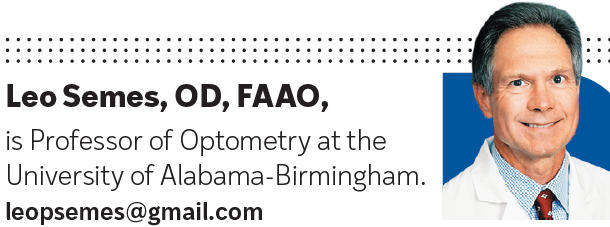

The circular portion in each is similar in size and corresponds to a contained retinal hemorrhage in the center of the macula that obscures what would be the normal foveal avascular zone.

Figure 2. OCT-angiograph of the right eye. In the top row, from left to right: superficial and deep retinal capillary plexus, outer retina, and choroidal capillary plexus. Middle row shows corresponding reflectance images showing outline of the hemorrhage. Bottom row shows cross-sectional OCT showing localization of the hemorrhage.

The retinal and choroidal capillary networks are regular and perfused. But, again, the center of the normal capillary plexus is obscured by the hemorrhage.

This becomes clearer looking at the reflectance images in the middle row of Figure 2. Finally, the OCT-A cross sections in the bottom row show the dense retinal hemorrhage that precludes view of underlying structures.

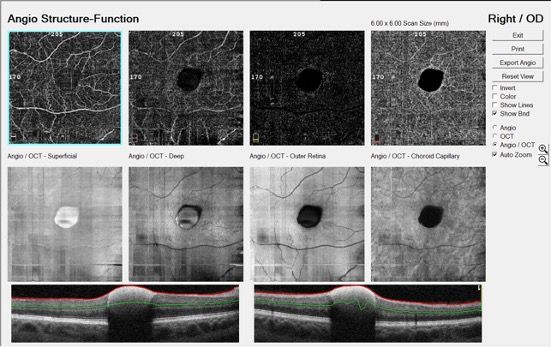

The inverted view (Figure 3) amplifies the characteristics and position of the hemorrhage. The OCT-A cross section is through the center of the macula, and the superficial retinal capillary layer is shown to the left.

Figure 3. Inverted presentation of the OCT-angiograph. Top row: similar to Figure 1, this shows sequentially deeper imaging of retinal and capillary circulatory systems. The bottom row highlights the superficial capillary plexus, which outlines the hemorrhage, while the OCT cross section illustrates its silhouette.

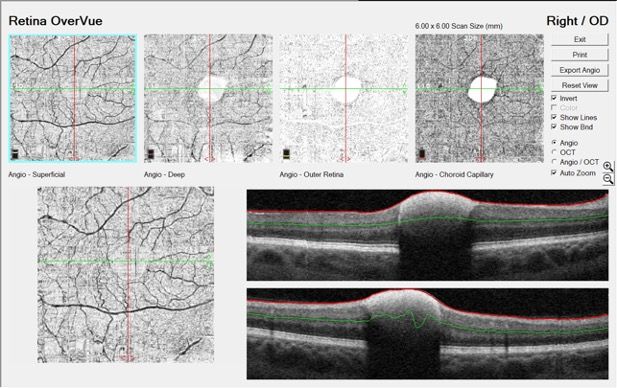

The angiograph in Figure 4 (bottom, left), shows the superficial capillary layer (left panel) with the corresponding angiograph below depicting capillary perfusion in red.

Figure 4. OCT-A of the right eye. Top row: Superficial capillary plexus and reflectance image. Bottom row: OCT-A cross sections showing circulation (red) in the retinal and capillary circulatory systems (left panel), but stagnation of blood within the hemorrhage.

The significant point that the angiograph demonstrates is the presence of retinal and choroidal perfusion surrounding the hemorrhage but no circulatory activity within it. The hemorrhage was stagnant, not circulating blood. It was contained within the internal limiting membrane and there was no evidence of macular edema.

Conclusion

It is very likely that the retinal hemorrhage in this case arose from a retinal arteriolar macroaneurysm. Similar findings were recently reported as away from the macula with resolution.1 Nonresolving lesions have been found to be amenable to treatments,2 and white-centered retinal hemorrhages have been associated with acute leukemia.3,4 Prognosis for complete visual recovery is typically guarded.5

The patient was reassured that the hemorrhage would clear with the promise of visual improvement. He was scheduled for follow-up in 2 weeks but did not return for follow-up.

References

1. Bekmez S, Eris D. Retinal arterial macroaneurysm in leukemia. Eur J Ophthalmol. Published online February 8, 2021. doi:10.1177/1120672121993781

2. Hanazaki H, Yokota H, Aso H, Yamagami S, Nagaoka T. Evaluation of ocular blood flow over time in a treated retinal arterial macroaneurysm using laser speckle flowgraphy. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. Published online February 2, 2021. doi:10.1016/j.ajoc.2021.101022

3. Chaabani L, Doulami K. White-centred retinal hemorrhage revealing acute leukemia. Tunis Med. 2019;97(6):822-825.

4. Huguet M, Balboa M, Vives S. Acute myeloid leukemia onset with bilateral retinal hemorrhages. Med Clin (Barc). 2022;158(2):98. doi:10.1016/j.medcli.2021.04.015

5. Tsujikawa A, Sakamoto A, Ota M, et al. Retinal structural changes associated with retinal arterial macroaneurysm examined with optical coherence tomography. Retina. 2009;29(6):782-792. doi:10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181a2f26a

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.