Vision rehabilitation of patients with stroke

Vision deficit associated with stroke is common, and many ODs will see these patients in their chairs

Low vision (LV) rehabilitation is a sub-specialty of optometry practice. This specialty and topic in general can lead to differing reactions in professional, academic, and social settings: boring, time consuming, and not economical are common negative thoughts whereas helpful, rewarding, and life altering are what others may say. I am lucky to have over a decade of experience providing this service to countless patients, and I want to shed a little light on why I think every OD who can help these patients with stroke and traumatic brain injury rehabilitation should.

Stroke, one cause of acquired brain injury (ABI), affects people of all ages and the eyes and routinely impairs the visual system. This article aims to help educate every OD regardless of practice modality how to identify and offer thoughts on how to help these individuals.

Evidence-based medicine should guide clinical practice, and luckily a study asked the question: Does low vision rehabilitation work? In 2017, fellow OD Joan Stelmack and colleagues published the Outcomes of the Veterans Affairs Low Vision Intervention Trial II (LOVIT II)—it showed intervention is important for all patients and that for many of our patients adding rehabilitation is very rewarding.1

Related: Vision rehabilitation care for low vision patients in the COVID-19 era

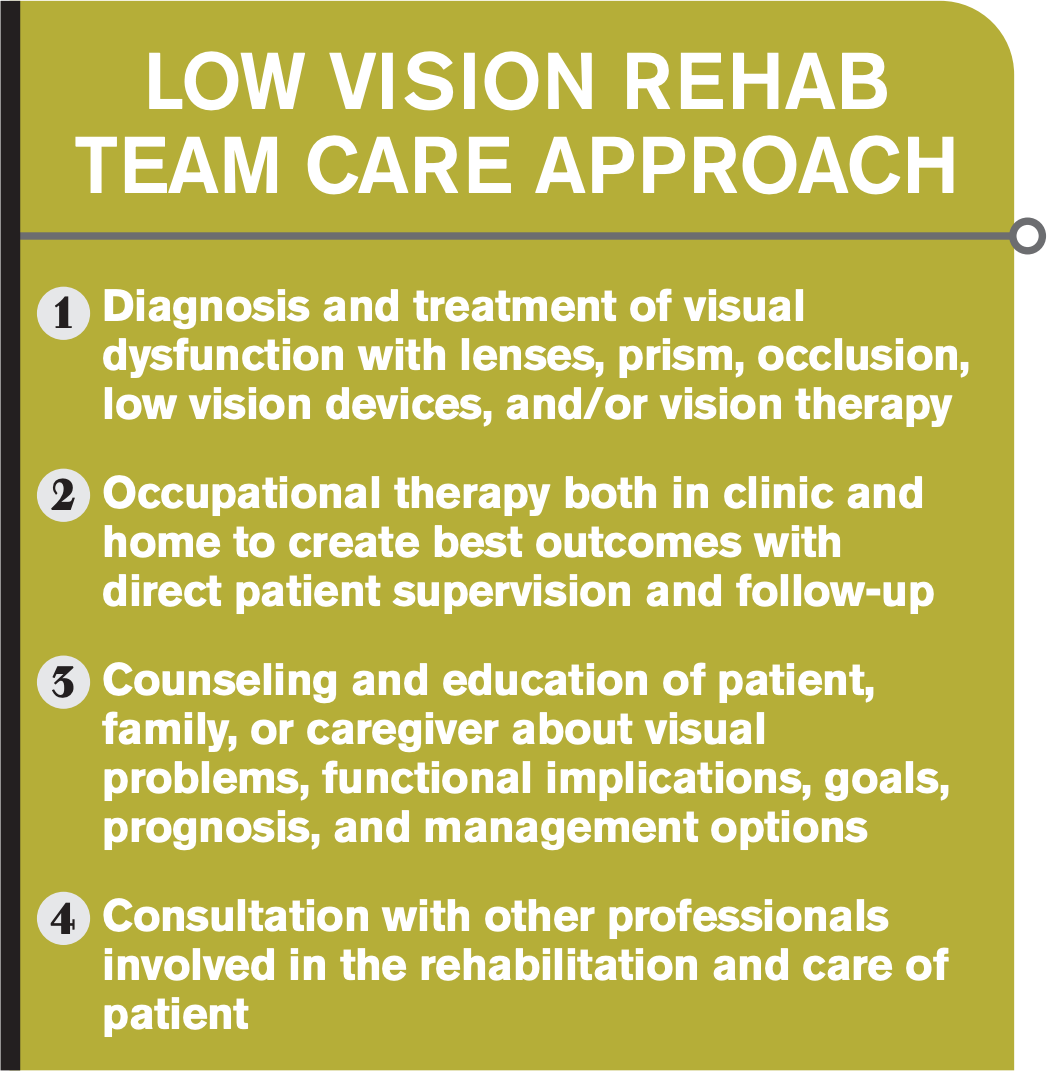

The approach of LV rehab is to diagnose and treat the visual dysfunction with lenses, prism, occlusion, low-vision devices, and vision therapy, followed by occupational therapy in both clinic and home settings. Key components in this process include proper counseling and education for patient and family regarding visual prognosis, goals, and expected outcomes as well as collaboration with other professionals involved in the care of the patient (see box).

Stroke and vision

Stroke in the U.S. is a serious disease, and according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report it kills about 140,000 Americans each year. Someone in the U.S. has a stroke every 40 seconds, and every 4 minutes someone dies of a stroke. About 87 percent of all strokes are ischemic and costs the U.S. an estimated $34 billion, which includes healthcare services, medicines, and lost work production. Finally, stroke is the leading cause of serious long-term disability and reduces mobility in over half of survivors age 65 and over.2

Figure 1

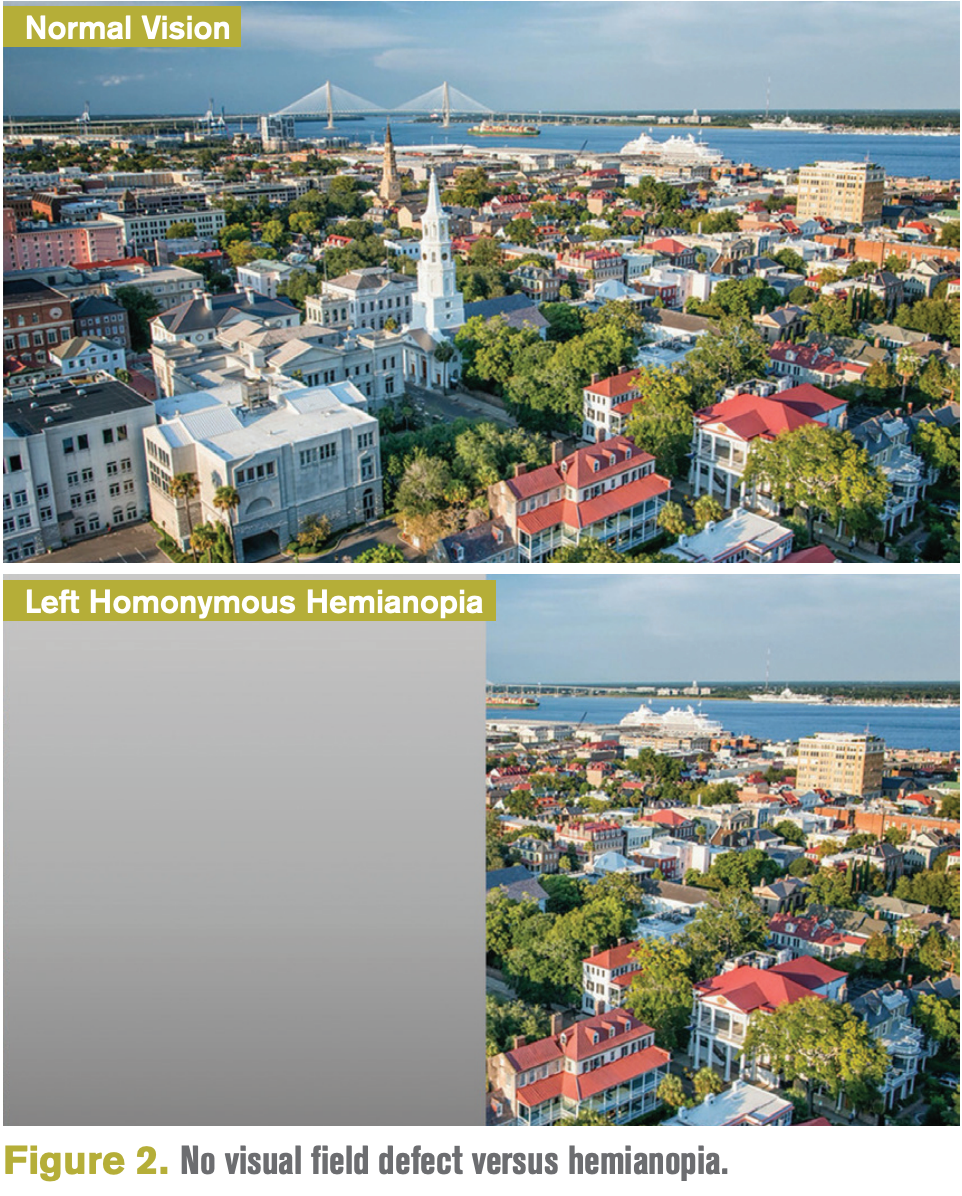

Common ocular complications associated with stroke include bilateral vision loss due to cortical visual impairment, hemianopsia, visual neglect, nystagmus, strabismus, photophobia, and visual fatigue among many others. With such a large prevalence and a myriad of associated neuro-ocular symptoms, there is a good chance stroke patients will end up in the chairs of their local optometrists. In Warren’s hierarchal model of visual processing, the skills at the bottom form the foundation for each successive level (Figure 1). Higher level skills evolve from the foundational skills and depend on complete integration of lower level skills for their efficient and skillful development.3

Related: How to care for stroke patients

In her model, the 3 foundational categories of oculomotor control, visual fields, and visual acuity are necessary to allow accurate conjugate eye movements and object identification. This allows the brain to engage attention on a scene, scan the scene to search for other relevant visual information, and process any relevant patterns. Without these foundational skills, visual memory, visual cognition and proper integration with other sensory modalities cannot occur. Altogether, our brain can manipulate visual information and integrate the constant stream of visual information with other senses to understand the total environment around a person.3

Case history

During my low vision exam as I prepare to take the case history (which is the most important part of any eye exam), I like to ask myself 5 simple questions:

1. What is this patient’s cognition level?

2. What is the level of learning capacity?

3. What is the awareness of potential?

4. Does this person have self-awareness of their visual deficit?

5. What is the level of complexity of the task that is this patient’s goal?

These questions help as we dive into my typical low vision exam. Case history is crucial to understand why the patient is seeking out your services.

Related: Resveratrol may be key in AMD stroke patient treatments

It is important to obtain the chief complaint, history of present illness, ocular history, functional complaints, performance of activities of daily living (ADLs), and rehabilitation history both inpatient and outpatient. It is important to observe the physical appearance (clothing, facial appearance, visual attention), head tilt or turn, mobility, motor weakness, and the patient’s support system.

Communication disorders such as expressive aphasia (Broca’s area 22), receptive aphasia (Wenicke’s area 44), and global aphasia are important to understand.4 Cognitive testing in clinic or from referral are helpful in understanding the full clinical picture. Communication with other rehab providers who know the patient—such as physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech therapists, and family members—can provide this information, especially in the setting of communication deficits.

Ocular exam

The ocular exam is crucial to understanding what the patient is experiencing. Visual acuity testing can be conducted by Snellen letter or number recognition, shapes and figures such as Allen or LEA figures, or the method of preferential viewing.

I recommend performing retinoscopy and refraction on every vision rehab patient because there may be confusion of old glasses or there may be neglect and the patient doesn’t realize his own best potential visual acuity. Checking the pupils, pursuits and saccades, binocular vision assessment, color vision, and contrast sensitivity are also valuable clinical findings that help with visual rehab.

Related: 5 exam findings that should spur a neuro referral

One of the most important tests regarding stroke is the visual field. Confrontational visual fields, Humphrey visual fields both automated and kinetic, Goldmann perimetry testing, and tangent visual field testing all can provide invaluable clinical data.

Field loss

The low vision rehab treatment plan includes 4 important tenants. First, it is the goal to restore or reeducate neuromuscular and oculomotor dysfunction. Second, introduce and reinforce compensatory training of visual system. Third, educate the patient and family about awareness of deficits and discuss risks and safety options. Finally, establish a continuum of care with the patient, family, caregivers, and other healthcare providers.

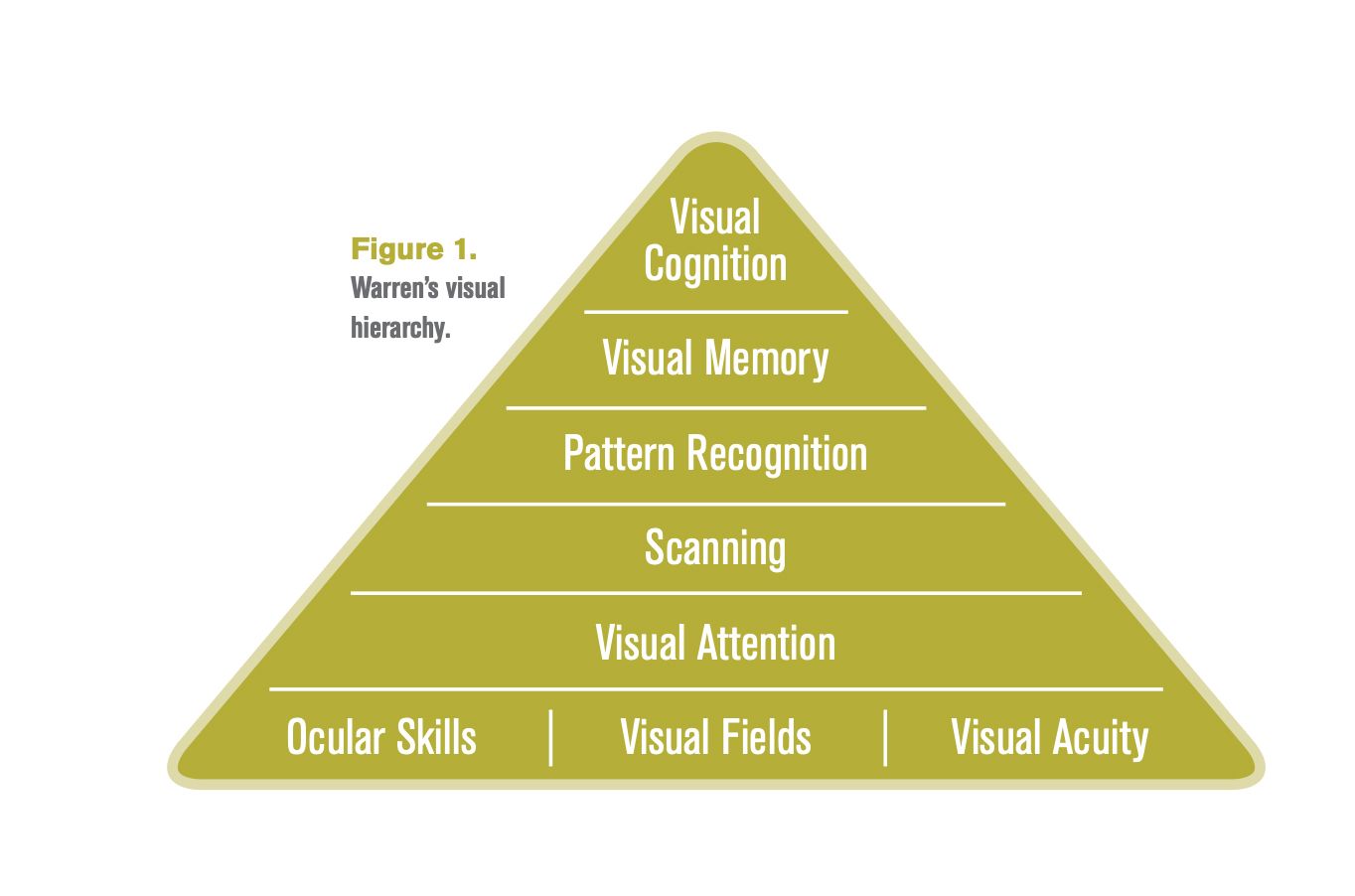

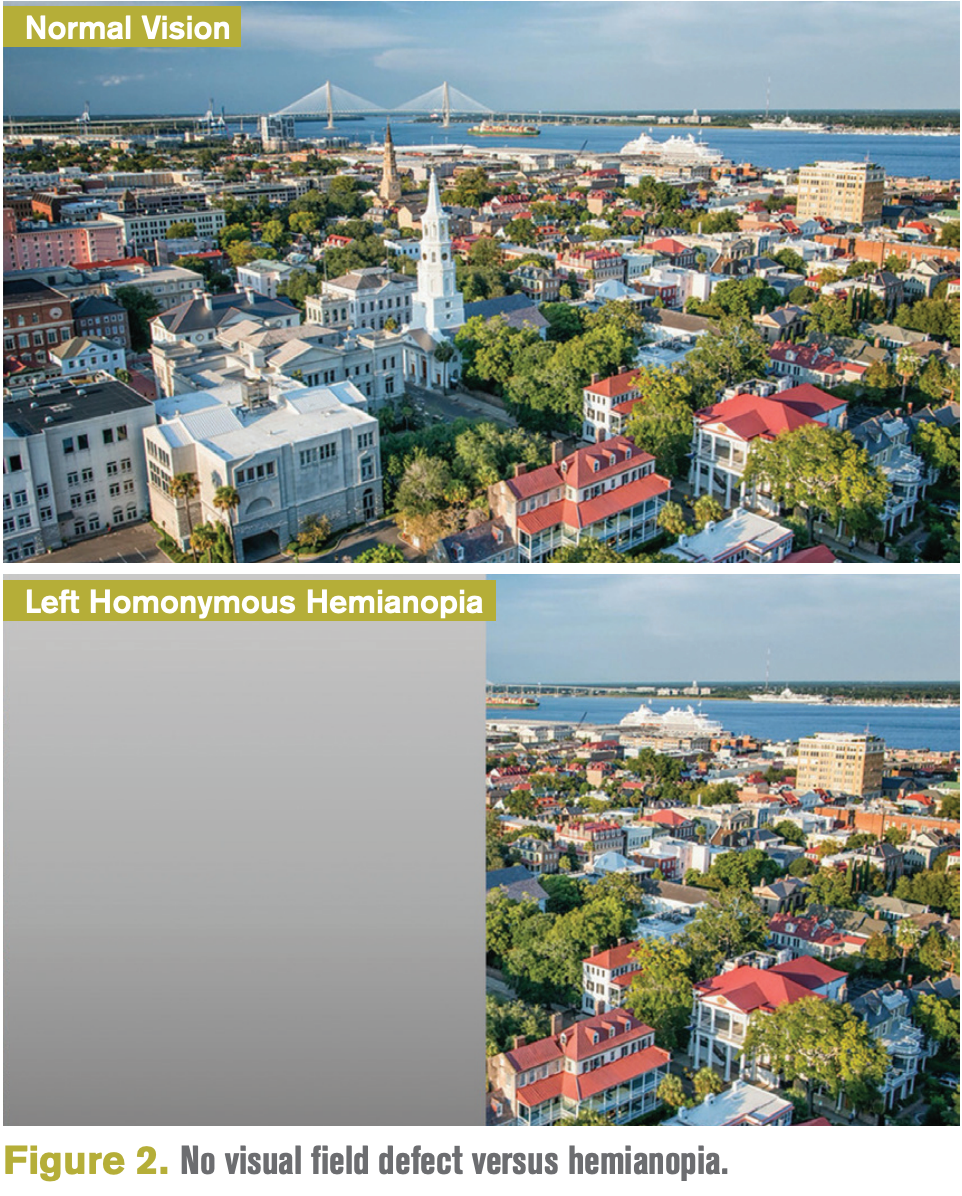

Stroke can present with many visual complaints and findings, and one of the most common is visual field loss. Hemianopia, or blindness over half the field of vision, is most common among cerebrovascular accidents. Research shows that visual field loss occurs in 49.5 percent in stroke survivors, and 29.4 percent had a complete hemianopia.6

Other types of field loss may include inferior and superior quadrantanopia, constricted visual fields, scotomas, and altitudinal defects. These changes have a direct impact on ADLs including mobility, reading, and driving. Difficulty scanning into complex situations while driving and walking in busy environments are frequently reported.6 Figure 2 shows an example of a comparison of someone with no visual field defect versus someone with a complete homonymous hemianopia.

Figure 2

Understanding hemispatial neglect is key for how a patient may respond to therapy. Left-sided neglect is associated with both right-sided middle cerebral artery (MCA) and posterior cerebral artery (PCA) cerebrovascular vascular accident. This neglect is many times a common finding with complete left homonymous hemianopia.

More by Dr. Hill: Review Chiari-related diseases and associated ocular symptoms

In-office tests will allow the optometrist to diagnose neglect. These cancellation tests include line bisection, clock drawing, and figure copy tests. Once neglect is diagnosed, prism adaptation therapy is the gold standard to help with recovery. Prism likely creates a recalibration of egocentric location by applying a 20 prism diopter yoke baseout left prism over both eyes. Research demonstrates that repeated exposure can substantially and permanently reduce various neglect behavior. The current therapy plan is in-patient rehab with 10 days of 20 minutes of wear time with the 20 prism diopter yoke based prism glasses.7

Treating the patient

Once a visual field defect and hemispatial neglect are determined, there are treatment strategies for hemianopia. In the low vision clinic, saccade training and scanning therapy are important for those who have lost half of their vision. This involves training the patient to search or scan into the area of the visual field loss that is missing.

Activities include head eye shifts; computerized trainers such as Dyna Vision, Vision Coach, and NeuroEye; descriptive walking, last-letter line readers, and others. Boundary marking trains the patient to search for a marker at the end of a line of text using a string on the index finger. Optical devices can help with gaining visual field that has been lost. Special prism lenses in eyewear include yoked sector prisms, unilateral sector prism, peripheral prism including Peli Prism, and the Geottlieb Visual Field Awareness System.

I trial peripheral Peli prism system on all patients with hemianopia. This lens system offers a measurable field expansion of up to 20 degrees at primary gaze without giving double vision in central vision (using a 40 diopter base-out prism). According to a 2014 paper, this is the only prism device shown to improve patient-reported detection and improved mobility in a multicenter placebo-controlled trial.8 It is relatively inexpensive and cosmetically acceptable, and double vision is limited to the periphery. As with any prism system, there are contraindication and side effects: it is not suitable for patients with cognitive impairment, glare can bother some wearers, and some patients may be confused by image shifts.

More by Dr. Hill: ODs’ guide to MRIs

In addition to cerebral vascular accidents, cranial nerve palsies present with unique visual problems experienced by patients. Cranial nerve VI (trochlear/superior obliques) have the highest prevalence of involvement in stroke due to the anatomical relationship close to the middle cerebral artery (MCA) and the posterior cerebral artery (PCA). This cranial nerve is responsible for intorsion, infraduction, and abduction; thus, involvement leads to complaints of vertical diplopia.

Cranial nerve III controls 4 of the ocular muscles, and if affected by stroke will lead to an eye that is down and out, leading to diplopia and possible ptosis. Cranial nerve VI (abducens/lateral rectus) is responsible for abduction and if affected can lead to esotropia and sometimes internuclear ophthalmoplegia (INO).

Treatment strategies for diplopia associated with stroke include using a short-term patch or fog lens. It is important to remember that a total blackout patch prevents peripheral retinal signals from sending information to the vestibular/magnocellular processing. A fog lens such as translucent tape or a Bangerter filter occlusion is best for higher level visual processing. This strategy is best used by alternating the patching between eyes to encourage binocularity. Another strategy is partial occlusion in the diplopic motor field to encourage reintegration of peripheral visual field awareness and increase binocularity. Binasal occlusion is thought to help with visual motor sensitivity and suppress the near retinal periphery.9

It is important to note that a full lens prism such as Fresnel for diplopia can lead to remaining double vision, but prism brings images closer together to promote eye learning.

More by Dr. Hill: How to diagnose a swollen optic nerve

Conclusion

Vision deficit associated with stroke and other acquired brain injury is very common, and many optometrists will have these patients in their chairs. There are many ways these patients can be helped with vision rehabilitation, and my hope is that the OD will work on suggested strategies or refer to another optometrist in the area who works with stroke and vision rehabilitation.

References

1. Stelmack JA, Tang XC, Wei Y, et al; LOVIT II Study Group. Outcomes of the Veterans Affairs Low Vision Intervention Trial II (LOVIT II): A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017 Feb 1;135(2):96-104.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Stroke Facts. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/stroke/facts.htm. Accessed 10/28/20.

3. Zoltan B. Vision, Perception, and Cognition: A Manual for the Evaluation and Treatment of the Adult with Acquired Brain Injury, 4th Edition. 2007.

4. Massof RW. A model of the prevalence and incidence of low vision and blindness among adults in the U.S. Optom Vis Sci. Optom Vis Sci. 2002 Jan;79(1):31-8.

5. Department of Veterans Affairs. Management of Stroke Rehabilitation. Available at: https://www.healthquality.va.gov/ guidelines/Rehab/stroke/stroke_full_221.pdf. Accessed 10/20/20.

6. Rowe FJ, Wright D, Brand D, et al. A prospective profile of visual field loss following stroke: prevalence, type, rehabilitation, and outcome. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:719096.

7. Frassinetti F, Angeli V, Meneghello F, Avanzi S, Làdavas E. Long-lasting amelioration of visuospatial neglect by prism adaptation. Brain. 2002 Mar;125(Pt 3):608-23.

8. Bowers AR, Keeney K, Peli E. Randomized crossover clinical trial of real and sham peripheral prism glasses for hemianopia. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014 Feb;132(2):214-22.

9. Ciuffreda KJ, Yadav NK, Ludlam DP. Effect of binasal occlusion (BNO) on the visual-evoked potential (VEP) in mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI). Brain Inj. 2013;27(1):41-7.

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.