CAM for the treatment of Sjögren syndrome–related ocular surface disease

Patient quality of life has been shown to be severely impaired by the associated ocular surface symptoms, so treatment aims for symptomatic relief and prevention of further damage to the ocular surface.

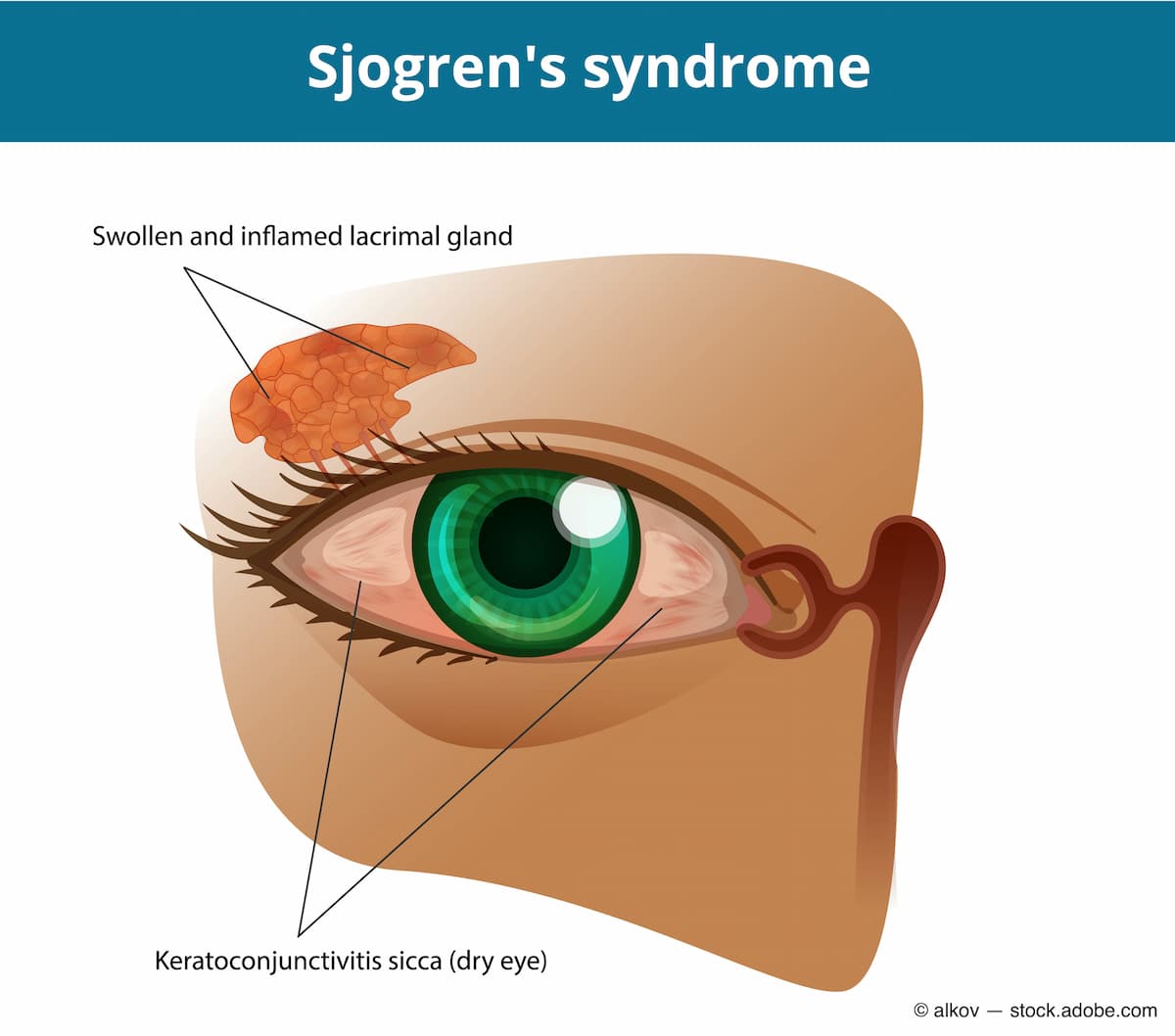

Sjögren syndrome is a potentially life-threatening chronic autoimmune disorder that can cause irreversible damage to exocrine glands, such as the lacrimal and salivary glands, resulting in a loss of tear and saliva production. As the tear film in patients with Sjögren syndrome becomes insufficient to keep the eye moist, this leads to ocular inflammation and dry eye disease.1,2 The quality of life for patients has been shown to be severely impaired by the associated ocular surface symptoms, so treatment aims for symptomatic relief and prevention of further damage to the ocular surface.1,2

Current treatment options

All current treatment options have been shown to improve the signs of ocular dryness and help control symptoms. These include artificial tears, punctal occlusion, topical anti-inflammatory eye drops, bandage contact lenses, scleral contact lenses, autologous serum drops, and oral secretagogues.1,2

Unfortunately, dryness of the ocular surface can be refractory to treatment in a subset of patients with Sjögren, which can ultimately result in significant complications involving corneal abrasions, infection, ulceration, scarring, and perforation. Therefore, further treatments remain necessary.1,2

For patients suffering from ocular surface disease, a potential therapy option that accelerates recovery of ocular surface health and corneal nerve regeneration is cryopreserved amniotic membrane (CAM). Issues such as pain, corneal staining, overall dry eye signs and symptoms (eg, discomfort, visual disturbances), and corneal sensitivity can be improved with CAM therapy.3 CAM, as a biologic corneal bandage, creates an environment for regenerative healing and is designed specifically for treating damaged corneas.4

As the only FDA-cleared CAM product, Prokera (BioTissue) supports the corneal healing process without harmful adverse effects. To help rapidly restore the cornea’s healing capabilities, Prokera’s CryoTek preservation method maintains CAM’s full biologic components.4

Prevalence of Sjögren syndrome

Sjögren syndrome is more common than we realize because it can vary in its presentation, and symptoms can be different for each patient. Some may present with dry eye or dry mouth, but they have not been to a doctor nor had any specific testing for diagnosis. Often, you can only suspect that patients have Sjögren syndrome, which is why it is underrepresented.

Diagnosing Sjögren syndrome

Whenever a patient comes in with a significant amount of unexplained dry eye, I consider their age and gender because Sjögren syndrome commonly affects individuals aged 40 to 60 years and is more prevalent in women. If I have a female patient in that age range with significant dry eye, my first question is whether they have any problems with dry mouth. The difficulty here is that patients cannot always differentiate those symptoms, so I rely on other tests.

A Schirmer test evaluates whether the eye produces enough tears to keep it moist. In a healthy patient, a Schirmer test takes about 5 minutes, and their fluid reaches about 10 to 15 mL of depth on the paper. A vast majority of patients with Sjögren syndrome, however, have little to no fluid coming out. This is when I start to suspect that something may be going on with the lacrimal gland. In this case, I would send them for blood and urine tests to look for certain markers. A salivary gland function scan, biopsy of the labial gland or the lip, or ultrasound of the other major glands is sometimes performed.

It is important for eye care practitioners to test anything that could be secondary or sequelae of dry eye. Therefore, I want to rule out diseases such as neurotropic keratitis, in which the patient has no feeling in the front of the eye. I can perform corneal sensitivity testing and staining and meibography as well, to rule out meibomian gland dysfunction. Also, I like to run through dry eye questionnaires with the patient to see how often or when they feel dry. If I have a patient who has run through many treatment options without relief, and they meet the age criteria, I will refer them to a rheumatologist and work with their primary care doctor.

There are two kinds of Sjögren syndrome. Primary Sjögren syndrome develops on its own without preexisting health conditions. But most patients I see have concomitant Sjögren syndrome, because they have some form of autoimmune disorder, such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, or psoriatic arthritis, and they already are working with a rheumatologist or their primary care doctor.

Treating Sjögren syndrome

Regardless of the origin of the disease state, one of the biggest challenges in dry eye is finding a cost-effective, long-term treatment that can best manage the condition to improve the patient’s quality of life. Many factors—such as diet, travel, environment, and use of digital screens—put undue burden and stress on the ocular surface.

When you have a patient who is already at a disadvantage because their autoimmune disorder is limiting their ability to produce good-quality tears—which are meant to provide anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and nutritional enzymes for epithelial tissue—you are working backward. My treatment originally involved keeping the eye lubricated, but I also look at the inflammatory aspect and sometimes start patients sooner on a neuromodulating anti-inflammatory agent.

The dry eye disease state has evolved in the past 30 years. Traditionally, dry eye was considered just a nuisance. Patients with severe, overt symptoms such as dry, scratchy, or irritated eyes with foreign body sensations were the ones whom clinicians attempted to treat, but there was no truly effective treatment available. At the time, there was no strong consensus that inflammation was the root cause.

The first FDA approved treatment was cyclosporine, which was regarded as a miracle and used in severe cases. But the biggest change was the use of anti-inflammatories, like steroids. In the past decade, we have looked at ways to return some of the proteins and nutrients that are important for natural tears to the eye. For example, eye drops made from autologous serum, the biproduct of spinning off the patients white and red blood cells to create a nutrient-filled tear, can do so.

In more challenging cases, I try to think differently. Thermal expression of the lids or intense pulsed light, for example, can reduce the amount of inflammation in and around the eyes. For patients with Sjögren, a long history of dry eye, and neurotrophic keratitis, the orphan drug known as cenegermin-bkbj (Oxervate; Dompe) is used to stimulate and reinvigorate the surface of the eye with some recombinant neural growth factor, helping the eye respond to these external challenges itself.

Lastly, amniotic membranes are a great treatment option. Most patients I see have significant dry eye. Especially for patients on the Sjögren spectrum, I would start them on an amniotic membrane. The amniotic membrane provides an opportunity for anti-inflammatory and healing properties. I am more likely to do so with a patient with a Sjögren syndrome diagnosis by a rheumatologist, because small, anecdotal studies have shown that patients get relief from using amniotic membrane. Although the relief may not last as long as for someone without Sjögren syndrome, the consecutive use of CAM tends to prolong relief.

Experience with CAM

My personal experience with CAM has been fantastic, especially in patients with Sjögren syndrome. It is important to prepare patients by giving them realistic expectations. For example, the polycarbonate ring tends to be the most uncomfortable part of Prokera. However, patients who have severe symptoms, poor vision quality, and who are tired of waking up in the morning with eyes feeling like sandpaper get excited to know there is a treatment option, regardless of some of the challenges or short-term discomfort.

Another challenge with CAM is that it does not penetrate the eye nor reach the lacrimal gland. For some patients with severe inflammation, it is unable to work directly on the gland but it helps reduce their inflammatory load. The benefit of using CAM is that we see results. We see CAM reduce inflammation in and around the entire ocular surface.

For practitioners who have never used CAM or are hesitant to try, my advice would be to find a patient who is symptomatic, with abrasion or recurring erosion and significant amounts of superficial punctate keratopathy, so you can see the benefit of using CAM after 3 or 4 days.

It just takes 1 patient, and then you will start to consider which others would be appropriate candidates. Although doctors may feel intimidated by having to put a ring in the eye and take it out, it is no different than placing a contact lens in the eye and removing it. You become more comfortable with experience, and if you give yourself enough time it will become second nature.

References

1. Shafer B, Fuerst NM, Massaro-Giordano M, et al. The use of self-retained, cryopreserved amniotic membrane for the treatment of Sjögren syndrome: a case series. Digit J Ophthalmol. 2019;25(2):21-25. doi:10.5693/djo.01.2019.02.005

2. Chen Z, Lao HY, Liang L. Update on the application of amniotic membrane in immune-related ocular surface diseases. Taiwan J Ophthalmol. 2021;11(2):132-140. doi:10.4103/tjo.tjo_16_21

3. John T, Tighe S, Sheha H, et al. Corneal nerve regeneration after self-retained cryopreserved amniotic membrane in dry eye disease. J Ophthalmol. 2017;2017:6404918. doi:10.1155/2017/6404918

4. Data on file. BioTissue, Inc, Miami, FL.

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.

2 Commerce Drive

Cranbury, NJ 08512

All rights reserved.