Vision care includes dry eye care

Diagnosing and treating dry eye and meibomian gland dysfunction can be the foundation for practice growth—and patient satisfaction.

As an optometrist in a progressive surgical practice, I know that dry eye disease (DED) is a major reason for dissatisfaction after cataract and/or refractive surgery. A poor-quality tear film can undermine success in every other aspect of surgery—the surgeon’s skill, the advanced intraocular lens technology, and all the effort we put into the patient experience.

But DED management is not just for surgical patients. In optometry school, we all learned that the tear film is responsible for 60% to 70% of the focusing power of the eye. If we want our patients to see well, to refract consistently, or to be successful in contact lenses, they need to have a healthy tear film. Any eye doctor who cares about vision should have a low threshold for recognizing and treating dry eye.

The insurance conundrum

Many doctors only truly look for DED when a patient comes in with “dryness” as a chief complaint. This will result in missing a huge percentage of the DED population, especially among vision-corrected patients who are in the practice for an annual examination under their vision insurance.

Here, I see clear parallels between managing DED and diabetes or glaucoma. If a patient came in for an annual exam seeking new glasses, but their intraocular pressurevwas 36 mm Hg, I would not just dispense glasses and say, “See you next year.” I would convert that visit to a medical exam and treat their glaucoma.

Likewise, if we detect moderate to severe DED, we convert to a medical exam and defer the vision exam to another day so that we can appropriately treat the disease, and then be able to get a better refraction later. In most cases, however, the DED is not severe, so in more mild cases I would complete the vision exam, discuss the need for more specialized diagnostic testing, and bring the patient back in a few weeks for a medical exam.

Going forward, just as a patient with glaucoma would have regular visual fields, optical coherence tomography, gonioscopy, and fundus photos, our patients with dry eye will be monitored more frequently with scheduled diagnostic testing and appropriate interventions.

Our standard of care for any patient with a known DED diagnosis or a positive Standard Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness (SPEED) score is to obtain osmolarity, meibography, lipid layer thickness, functional gland counts, and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) testing at baseline and repeat at regular intervals or when new signs and/or symptoms justify retesting. Given that up to 87% of patients with DED have meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) as a component of their disease, we also routinely assess the function of the lids and meibomian glands at the slit lamp.

To justify billing for diagnostic testing and interpretation, it is essential to react to those metrics with a management plan. Very commonly in our practice, that includes a procedure to evacuate blocked meibomian glands and restore normal meibum function. Poorly functioning glands do not fix themselves. Testing for them is great, but you must treat what you see, too.

MGD protocols

When I diagnose mild MGD, I tell patients that we have treatments available but that I want them to try some simple at-home measures first. We send the patient home with instructions to use warm compresses, perform lid hygiene, and take nutraceuticals for 4 to 6 weeks. These measures are like the brushing, flossing, and mouthwash our dental colleagues recommend—a bare minimum for prevention and maintenance, not a medical treatment for disease.[RP1]Please confirm that expansion is correct.

After the 4 to 6 weeks, I see the patient again and evaluate the lids and glands closely and compare with their baseline. When warranted (and it usually is), I discuss my treatment recommendation in more detail, which will include thermal pulsation treatments.

Although there are now several FDA-approved platforms that target removal of meibomian gland obstruction, LipiFlow vectored thermal pulsation therapy (Johnson & Johnson Vision) continues to be my gold standard. It is unique in being able to heat the glands from the inside of the lid to liquefy the meibum safely, and apply pulsed pressure to all the glands simultaneously on the upper and lower lids of both eyes to help expel material efficiently.

Figure 1a

Figure 1b

Figure 1c

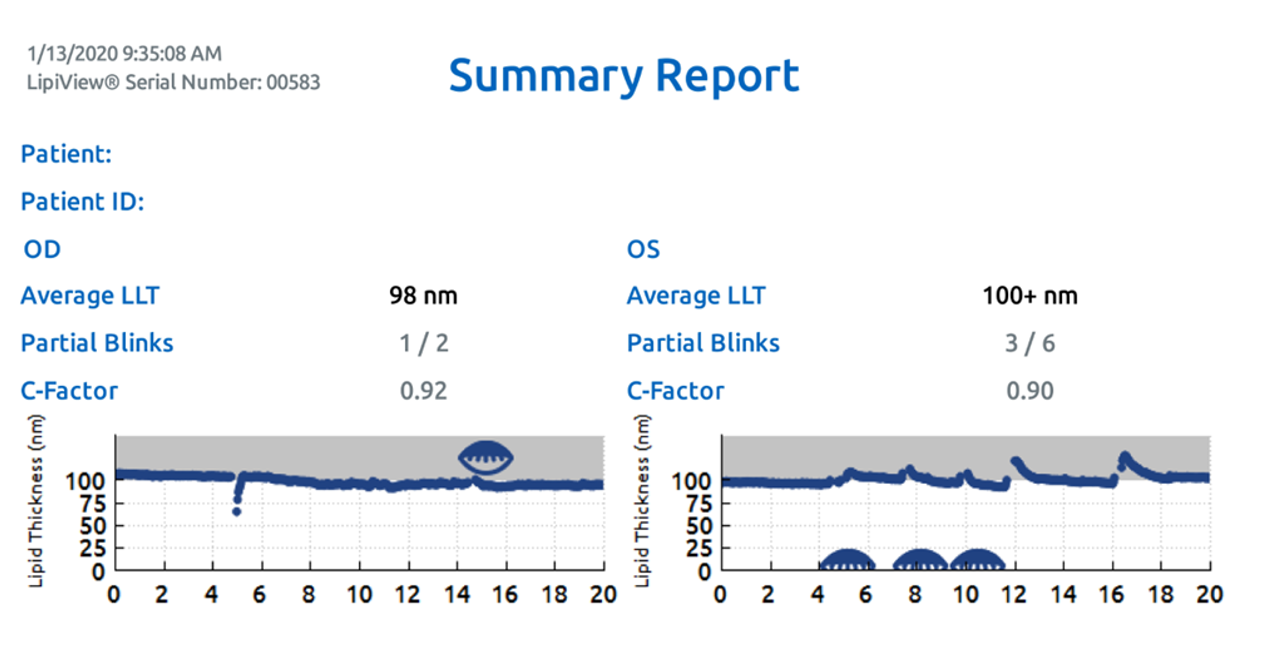

Figure 1a-c caption: This asymptomatic patient with dry eye had a SPEED score of 0. Baseline meibography for the right (a) and left (b) eyes is shown. The functional gland count was 13 OD and 16 OS, with grade 2 meibum quality in both eyes. The baseline lipid layer thickness is shown in Figure 1(c). This patient was educated on the need to treat meibomian gland disorder to prevent progressive damage to the glands and to improve overall eye health and function.

For me, it is gland function and meibum quality, rather than gland structure, that determine whether I recommend LipiFlow (Figures 1 and 2). The ideal conditions for treatment are when the patient has normal meibography but compromised function, because the patient has an excellent chance of restoring good lipid function, reducing the risk of meibomian gland structure loss. Additional adjunctive therapies may be needed to address other contributors to dry eye, and we use other procedures to complement LipiFlow.

Figure 2: After initiation of supportive dry eye treatments and a few follow-up appointments, the patient agreed to a bilateral LipiFlow treatment. Six weeks after treatment, the lipid layer thickness is improved, and functional gland counts have improved to 22 OD and 21 OS with grade 3 meibum quality OU.

Some patients do not accept our treatment recommendation right away, and that is fine. Cost, awareness of DED and MGD, or uncertainty about an unfamiliar treatment may be barriers. Regardless, we are going to continue to monitor that patient for progression, perform diagnostic testing at regular intervals, and continue to recommend appropriate treatment. DED and MGD are chronic diseases that patients will have for life; we cannot give up on them.

Cyclosporine, lifitegrast, and Tyrvaya nasal spray (varenicline solution, Oyster Point) are also first-line friends in the fight against DED. These agents can increase tear production, improve osmolarity, and reduce inflammation—but they are not indicated for MGD and have little to no effect on the meibomian glands if they are obstructed.

Healthy eyes, growing practice

In addition to being good for patients, treatment of dry eye is also good for practice growth. It opens the door to higher-level coding for increased exam complexity, diagnostic testing and test interpretation, and cash-based services. DED patients often say, “No one ever told me I have this.” They perceive us as offering a higher level of care than they have received elsewhere, and that is reflected in our word-of-mouth referrals.

For our 7-doctor practice (2 MDs/5 ODs), cash-based dry eye services alone (not including diagnostics or procedures covered by insurance) bring in more than $150,000 per month. We are “all in,” with all 7 providers adhering to consistent standards of care. Success—both in making dry eye a consistent clinical focus and in making it a revenue generator for the practice—does require a conscious decision to change the practice culture from the top down. Depending on your starting point, available technology, and the degree to which a practice embraces dry eye care, the impact on the bottom line of adding DED medical care can range anywhere from a 5% to 10% revenue increase to more than 30%.

Dry eye management represents an enormous opportunity to enhance patient care and the practice bottom line at the same time.

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.